The final bag was eighteen small corpses having a total weight of perhaps a pound. Crespi regarded this as a success, and an excellent return for the expenditure in ammunition and effort. The passion for hunting, he said, could come even before the pursuit of love, and be equally remote from the balance sheets of gain or loss. Ferdinand of Naples had spent the equivalent of several million pounds on building his palace at Capodimonte just because this hill was on the route of migrating beccafiche—warblers of all kinds—and having finished the palace, a road to Naples had to be built at the cost of another million or two. It was estimated, said Crespi, that every warbler eaten by the royal sportsmen had cost the nation a thousand ducats.1

Not that I remembered it perfectly, but I’ve been thinking about this paragraph since the summer of 2005, when I read it in Norman Lewis’s account of the Allied occupation of Naples. The extraordinary claim that the existence of the massive art museum on the hill overlooking the city could be attributed to the desire of a prince to hunt beccafiche seemed too farfetched to be true.2 Yet I also knew that one should never underestimate the passion of ancien régime royalty for shooting.

I never looked into the matter, choosing to live wondering rather than knowing, but once I decided to write about the Capodimonte Museum, it seemed appropriate to check.

*

It was not Ferdinand of Naples who had the palace built, but his father Charles, the first of the Bourbon kings of Naples and Sicily. Charles, born in Spain, was sent to Florence as a teenager, where he resided at the Pitti Palace. According to British diplomat Sir Horace Mann, “he amused himself by shooting with a bow and arrow at the birds in the fine tapestry-hangings of his rooms, and was become so very dexterous that he seldom missed the eye he aimed at.”3

Mann is quoted in Harold Acton’s The Bourbons of Naples, 1734–1825, a book with much to say about Charles’s passion for hunting, which was such that the life of his court “revolved around hunting and shooting to an inordinate degree.” The punishments for poachers were severe: seven years of confinement for nobles, seven years in the galleys for commoners. The discovery of a pheasant’s feather in a private home was considered grounds for torture. Acton does not mention beccafiche but he notes that cats were banned in the vicinity of royal hunting grounds, which points to an interest in catching songbirds.

A more scrupulous work of history than The Bourbons of Naples might tell us how often poachers were punished, and with what severity, rather than only giving the official penalty. Still, I’m inclined to trust Acton at least in general terms; the fact that he was a Bright Young Thing should not be held against him, and if the book lacks footnotes, it at least has a bibliography that lists plenty of primary texts.

My next source was an earlier one, an English translation from 1858 of Pietro Colletta’s Storia del reame di Napoli dal 1734 sino al 1825, originally published in 1834. I came across the beccafiche right away.

Almost at the same time the king planned the erection of another villa upon a height near the city called Capo-di-Monte, for no other reason than because he heard that the small birds called beccafichi abound in that place during the month of August. Many of the works of this monarch owed their origin to his inordinate passion for the chase; had his object been nobler, such as the promotion of the arts, the protection of the frontiers, or commerce, these enormous expenses would have been more worthy of a good prince, and have been more thankfully acquiesced in by the people.4

After reading this I returned to Acton, looking for references to Colletta. I found several, including one in which Colletta is accused of “[a] tendency to subordinate facts to phrases, with an added resolve consistently to blacken the Bourbons.”

Finally I found a history of the palace by Robin Thomas, an art historian at Penn State. There are no beccafiche in his account.

Begun as a hunting park with a proposed lodge in 1735, in 1737 the court instead approved a monumental palace for the site. Work began on this palace in 1738, but by the 1750s it was only partly completed, and at that time the truncated building was converted into a museum for the Farnese Collection.5

I emailed Thomas to see if he had any thoughts on the matter and he was kind enough to respond. An excerpt from his reply:

…there is maybe a kernel of truth in what Colletta says. He tends, on the whole, to favor reductive anecdotes to explain several of Charles’s commissions.

What we do know:

Capodimonte was begun as a hunting reserve near the city. It possessed some existing hunting grounds that belonged to one noble family (conceivably these woods were best for hunting birds). Other properties were added to make this smaller reserve into part of a larger hunting park (which was soon stocked with a variety of game). It would never have been regarded as a site just for hunting beccafichi.

The palace project came in a second moment a couple of years later. It was conceived as an architectural and artistic monument rather than a mere hunting lodge.

The expensive road to the palace (lamented by Lewis) was created in the Napoleonic period, so not by the Bourbons at all. Capodimonte was Joseph Bonaparte’s preferred residence, and the old roadway leading up the hill was judged too small and difficult to climb (it always had been).

I guess, then, that I’ll call it a masterful slander, an unforgettable, misleading story that, damning the Bourbons for frivolity, contains enough truth that it cannot be called a lie.

*

The Farnese Collection that Thomas mentions was brought to Naples by the same Charles who ordered the construction of the palace. He inherited it from his mother, Elisabeth Farnese, the last of her family. It had been formed over the previous two centuries, especially during the papacy of the Farnese pope, Paul III (1534–1549). Today the collection is divided between the Capodimonte Museum (modern works) and the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli (antiquities). There’s more below about the history of the collection but for present purposes let it suffice that (i) it is rich in Renaissance painting and (ii) it includes the work of few, if any, Neapolitan artists. That is, the founding collection of the Capodimonte Museum is Roman.

When I visited in May the museum was half a year away from the end of a long renovation. Many galleries were still closed; others had been rearranged so as to keep major works on view. This means I can’t be sure what the exact layout will be when it is fully reopened next January, but it’s safe to expect a division into three parts: (i) painting and sculpture from the Farnese Collection, plus later non-Neapolitan acquisitions; (ii) Neapolitan painting and sculpture; and (iii) everything else—porcelain, tapestries, arms and armor, the royal apartments, works on paper, contemporary art, and so on.

Given this division, the visitor faces a dilemma: whether to start with the Farnese Collection or the Neapolitan one.6 The decision matters because both collections are large; if you choose to see the Farnese works first, you’ll be more than half exhausted by the time you get to the Neapolitan ones, and vice versa.

The Farnese Collection has renowned masterpieces of the sixteenth century by, among others, Raphael, Titian, Parmigianino and Bruegel. The Neapolitan collection on the other hand has only a handful of well-known paintings—one by Caravaggio and two or three by Jusepe de Ribera. But as anyone who has been to the museum knows, there is far more to Neapolitan art than Caravaggio and Ribera. Is it better to stumble upon the work of Luca Giordano or Mattia Preti than it is to get close to Titians and Bruegels already familiar from reproductions? I don’t know the answer. In this post I’ll split the difference by mostly writing about Neapolitan works, but starting with two Farnese ones.

*

Specifically, I’ll start with Bruegel, because this was always my other question about the Capodimonte Museum—as well as wondering about the beccafiche, I wanted to know how the museum’s two Bruegels got there.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder is not an artist whose work was sought after by Italian collectors. Most of his paintings, today, remain in Northern Europe. The ones in Naples, The Blind Leading the Blind and The Misanthrope, are first documented in 1612, in an inventory of the possessions of Count Giovan Masi of Parma. He must have inherited them from his father Cosimo, an art collector who had spent a few years in Brussels in the 1590s in the employ of the Farnese, and who had returned to Parma with some paintings. Count Masi ended up losing his father’s Bruegels, not to mention his head, because in 1611 he joined a conspiracy to assassinate Ranuccio I Farnese, Duke of Parma and Piacenza—the 1612 inventory in which the paintings are recorded was taken to document the confiscation of his possessions.7

I will say only one thing about the paintings themselves, namely, that they surprised me because most Bruegels, painted in oil on panel, are vividly colored, and these on the other hand are uncharacteristically muted. It turns out they are Tüchleins, works on canvas bound with hide glue. Many Tüchleins were made in the Netherlands in Bruegel’s times and earlier, but they are fragile, and few have survived. Perhaps the essential factor that preserved these was the good custodianship of the Farnese and the Bourbons, or else the Italian climate?8

*

The best-known Neapolitan art was made by artists who came to Naples from somewhere else. Caravaggio worked there twice, first right after he fled Rome, in 1606, and then again in 1609; both stays were brief, but his influence was felt in the city for decades to come. The Spaniard Ribera, a native of Valencia, arrived in Naples at the age of twenty-five in 1616, and remained until his death in 1652.

I won’t include the here the Capodimonte Museum’s sole Caravaggio, the Flagellation of Christ, as it was on loan when I was there, to the Palazzo Barberini in Rome for its Caravaggio exhibition. Ribera I will get to shortly, but the painter to start with is one you likely haven’t heard of, an artist active in Naples in the mid-fifteenth century, Niccolò Antonio Colantonio. The Capodimonte Museum had two of his works on view when I was there; a third one, a sign indicated, was undergoing restoration; I believe there is also a fourth.

The history of Naples is complicated. Colantonio may have worked in the city both before and after 1442, the year it went from being an Angevin possession (that is, ruled by the king of Anjou) to an Aragonese one. No one knows for sure, but the best way to explain his style, which is such that it makes one wonder if Naples was somehow closer to Bruges than it was to Florence, is to say that he was influenced by Barthélemy van Eyck, a Flemish painter in the service of King Réné of Anjou. The theory goes that Barthélemy must have been sent to Naples for a commission, or else paintings by him were brought there, and that contact with Barthélemy, or if not him then with his precise, Flemish style, was formative for Colantonio. Much hangs on the question because in addition to having left his own small body of work to posterity, Colantonio trained another artist, the great Sicilian Antonello da Messina. The question, how did Colantonio learn to paint like that? is thus an essential one for admirers of Antonello.

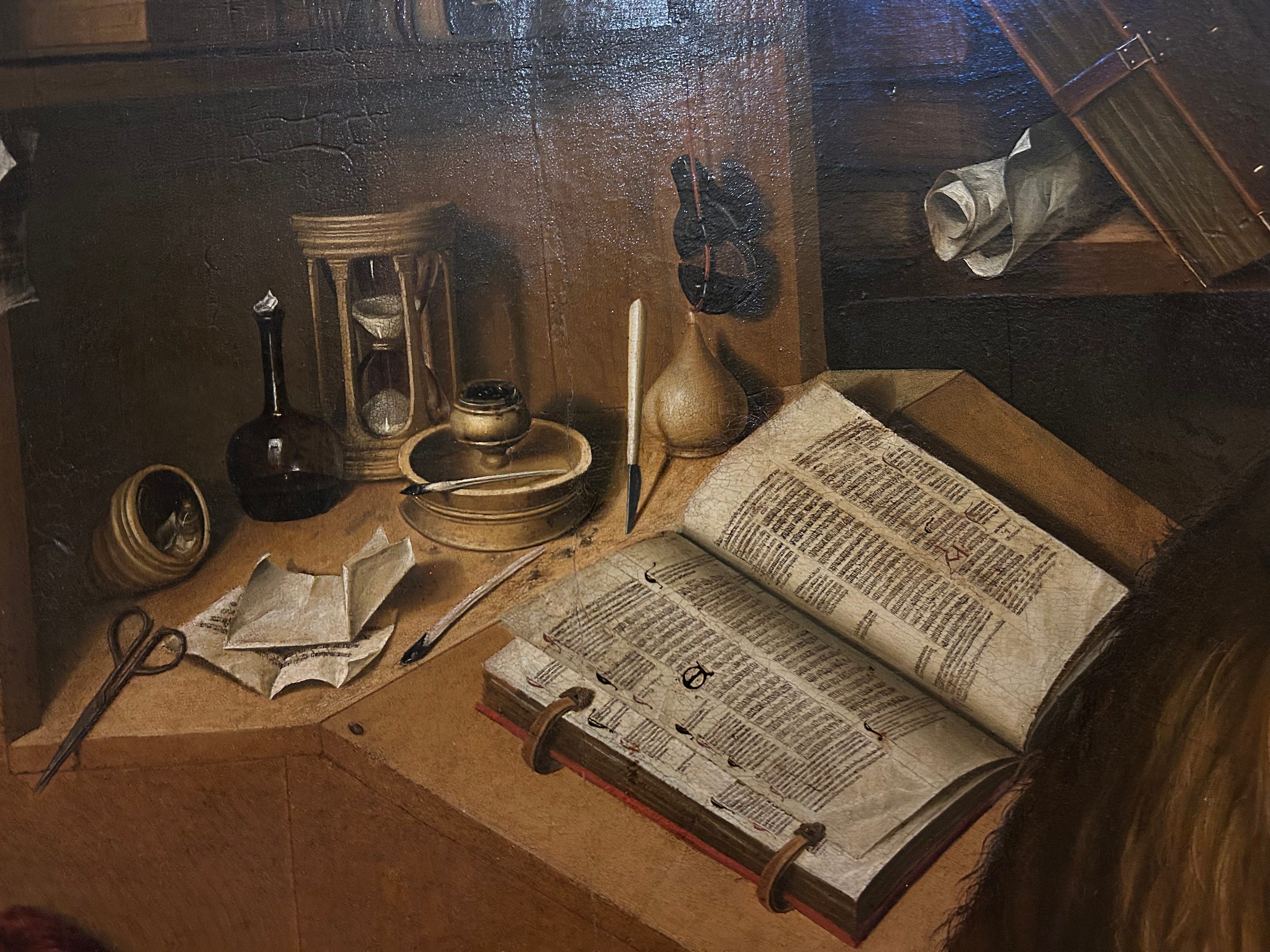

According to the Golden Legend and other hagiographies, Saint Jerome once pulled a thorn from the paw of a lion that wandered into his monastery. Jerome is not said to have been in his study at the time (“One day toward evening, when he was seated with the brethren to hear the sacred lessons read, a lion suddenly limped into the monastery.”9), but because he is associated with scholarship, paintings of Jerome and the Lion are sometimes set in his study—or I maybe I should turn that around and instead say, paintings of Jerome in his study sometimes incorporate the lion.

Either way, this is the scene shown in my favorite Colantonio painting, originally one panel of a large altarpiece in San Lorenzo Maggiore, one the Franciscan churches of Naples (Jerome is considered to be a proto-Franciscan). What’s most remarkable here is all the paper. The wall label dates the painting to c. 1445, which is after Gutenberg had invented the printing press, but before many books had been printed with it. The books on the shelves behind Jerome, then, must be in manuscript, and are likely on parchment rather than paper. But even if they are on parchment, there are sheets and scraps of paper scattered among these books, on and around Jerome’s desk, and even on the floor.

I wanted to propose that Jerome, surrounded by paper in this fashion, is an early adopter, but on looking into the matter it seems that he is not. It is true that paper came late to Christian Europe, more than a thousand years after it was invented in China, and centuries after it spread throughout the Islamic world, but the first Italian paper mill opened in 1276, and during the fourteenth century Italians supplied paper to the rest of Western Europe.10 What this likely means is that in Colantonio’s time paper may still have been a luxury good in some places, but not in Italy. Jerome, then, is probably not represented here as a scholar who has made a point of embracing the latest technology. He is, though, rather well-off, and, of course, notably fearless.

Another of the Colantonios at the Capodimonte Museum is the Delivery of the Franciscan Rule, a larger panel from the same altar as Jerome in his study. This is the one that was in the conservation studio. I can’t wait to see it on my next visit, whenever that may be.

*

As I suggested above, the painter most associated with seventeenth century Naples is Ribera, Lo Spagnoletto (‘the Little Spaniard’). It would be unfair to his originality and versatility as an artist to call him a follower of Caravaggio, but at the very least he was a sometime imitator. His works are dispersed far and wide, but some of the best ones are still in Naples. There’s the large painting of the city’s patron saint in Naples Cathedral, Saint Januarius Emerges Unscathed from the Furnace; there are the fourteen prophets and patriarchs in the arches of the nave of the church in the Carthusian monastery; and there are the Riberas at the Capodimonte Museum, among them a kitchen still life with a bloody goat’s head and a basket of eggs, and the Drunken Silenus, which is so ingeniously constructed, so richly detailed, and so hard to look away from, that I suspect that if one were to travel back to 1626 to inform Ribera of the work’s fame today, he wouldn’t be surprised. What other reputation could such a painting acquire? Again and again I look from Silenus at the center to the braying donkey at upper left, and then back down to Silenus; I never fail to smile.

These two are probably my favorites, but there’s one more Ribera I want to mention. In a room set aside for paintings dislodged from their normal galleries by the renovation, Ribera’s Apollo and Marsyas of 1637 hangs next to another interpretation of the same scene (Apollo, having vanquished the satyr Marsyas in a musical competition, begins to flay him). The second painting was made two decades later by Luca Giordano, an artist whose career somewhat inverts Ribera’s. Ribera came to Naples from Spain; Giordano by contrast spent most of his life in his native Naples, but in 1692 went to Spain for a decade to paint for Charles II.

I like both paintings, but on close inspection am inclined to prefer Giordano’s version, because his Apollo, to steady himself as he cuts into the flesh of Marsyas, places a blue-sandaled foot on the satyr, revealing—perfect, gritty Neapolitan detail—dirty toenails. Early in the century Caravaggio had caused a minor scandal in Rome when he painted an altarpiece featuring a pilgrim with dirty feet; I wonder if anyone objected to Giordano’s still earthier portrayal of a Greek God.

*

Around the time I got to Naples I received an email about an event at the Capodimonte Museum, the fourteenth annual Italian Art Society/Kress Lecture, given this year by Jesse Locker of Portland State University. The timing didn’t work; the lecture was on May 30, the day after my train to Rome, but I am glad I was at least able to read the abstract.

It is emblematic of the sometimes-impenetrable history of Naples that one of the city’s leading painters of the seventeenth century remains nameless: this is the Master of the Annunciation to the Shepherds, so-called for his portrayals of ragged, dignified shepherds painted with a thick impasto, murky earth tones, and strong contrasts of light and dark. Despite no consensus on his name, through his paintings we have a remarkably tactile and specific representation of the world he inhabited and the objects he owned: We can identify specific books and plaster casts he owned, recognize musical instruments, carpets, mirrors, costumes, copper pots and pans, maiolica pitchers, pewter vessels, and other wares, as well as apprentices and a range of models. Given that nothing else is known about the artist, these mundane objects can hold an important key to understanding both his art and place in the world of Neapolitan painting more broadly.

For those unfamiliar with the process at work here, a body of paintings has been identified by art historians as seemingly made a single, unknown artist. Until an identification is made, the artist is known as the Master of X, with X referring either to a specific painting (in this case, a painting of the annunciation to the shepherds), or to the place where the artist worked. Sometimes these puzzles are solved. The artist once known as the Master of the Barberini Panels is now agreed to be Fra Carnevale; the Master of Flémalle is Robert Campin.

In the case of the unknown Neapolitan, two paintings of the annunciation to the shepherds are attributed to him. There’s a large one in Birmingham, England and a small one at the Capodimonte Museum. Judging by the latter, it’s easy to see what the excitement is about. I hope Locker’s talk will be published soon.

*

There’s one more semi-Neapolitan artist I want to mention, Mattia Preti. Preti was a Calabrian who, after working in Rome in his youth, spent most of the 1650s in Naples. I say only the bare minimum here, in order to save him in case I ever visit the art museum in Toledo, Ohio, which has his Feast of Herod. There are three more feast scenes by Preti at the Capodimonte Museum—the Feast of Absalom (below), the Feast of Belshazzar and the Return of the Prodigal Son, and it turns out there’s a another in London, the Marriage at Cana, and still another in a private collection, David Playing the Harp before Saul. I don’t know what kind of crowds an exhibition of “Preti’s Feasts” would draw—as I said above, Ribera is the only big name of the Neapolitan seventeenth century. But on the other hand the Met’s 2017 show devoted to Valentin de Boulogne, the French follower of Caravaggio, was a success, so why wouldn’t Preti do just as well, if these big, action-packed canvases could be brought together?

*

And a final Naples painting, by the French eighteenth century artist Pierre-Jacques Volaire, who settled in the city in 1767 and established himself as a painter of scenes of the city’s surroundings, souvenirs for Northern European tourists. He is best known for views of Vesuvius erupting, and there was one such work on display in May, but I choose instead an image of the Solfatara, a sulfur-spewing crater near the town of Pozzuoli that was an essential stop on the Grand Tour in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Goethe was in the vicinity on March 1, 1787.

A boat trip to Pozzuoli, easy drives on land, pleasant walks through the most amazing region in the world. The clearest sky above, the most unstable ground below. Ruins of what was unimaginable affluence, mutilated and depressing. Boiling waters, holes exhaling sulfur, slag heaps resistant to plant life, bare, loathsome areas, but then at last an always lush vegetation, taking hold wherever it can, rising over all the dead things, surrounding the lakes and brooks, even maintaining the most magnificent oak forest on the walls of an ancient crater.11

*

The Farnese Collection is so good that it would be a shame to include only the two Bruegels, so I will finish this post with one more Farnese work, a painting that shows the founding of the church it was made for, the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. By Tommaso di Cristoforo Fini, usually known as Masolino da Panicale (which can be rendered in English as ‘Tommy from Panicale’), it was one of the central panels of a two-sided polyptych that Masolino collaborated on with the great Florentine, Masaccio.

The painting shows a miracle that took place either in August 352 or August 358 (accounts vary), when, in spite of the Roman summer heat, there was a snowfall. In one version of the story, the snow outlined the footprint of a basilica, which Pope Liberius (r. 352–66) proceeded to found as Santa Maria Maggiore; in another the snow fell generally over Rome, and it was Liberius who traced the shape of the church. It is hard to say which version Masolino’s painting portrays; the snow, though it continues to fall from a large disc of a cloud overhead, has already taken the shape of the church, but then Liberius wields a spade, so perhaps this is his handiwork we are seeing. Above the cloud, Christ and the Virgin preside over the scene; smaller discs similar in shape to the central one fill out the golden sky, but it is unclear whether or not these, too, are snow clouds.

The altarpiece was commissioned by Martin V (1417–31), the pope who ended the western schism (r. 1378–1417), a period when there were multiple claimants to the papacy. After his election in Constance, Martin made his way to Rome via Florence, where he may have encountered Masolino. Martin is known for his efforts to beautify Rome; it is likely that the scene with Liberius and the snowfall contains an implicit reference to this aspect of his papacy.

Though it was originally the main altarpiece of Santa Maria Maggiore, by the early seventeenth century the polyptych had passed from the church into the hands of the Farnese, its main three panels sawed in two to create six paintings rather than three. The side panels (today in Philadelphia and London) were sold off, but this central one, along with its verso companion, the Assumption of the Virgin, were still with the Farnese (with both works attributed to Fra Angelico) when the family collection was brought to Naples.

It is a splendid subject for a painting. There are a few more versions, including the one that replaced Masolino’s at Santa Maria Maggiore, a Mannerist work by Jacopo Zucchi, now in the Pinacoteca Vaticana. There’s also a small painting of the miracle by Pietro Perugino that is now in an English country house. Both the Zucchi and the Perugino are interesting, but it is a scene so rich in possibility that I long to see what other artists might have done with it, especially Flemish artists, especially Bruegel.

Crespi was an engineer Norman Lewis befriended while in Naples. On October 10, 1944, Lewis accompanied the Crespi family to the Lago di Patria, west of Naples, for an afternoon of hunting and mushroom foraging. Norman Lewis, Naples ‘44, 1978, 178–79.

As Lewis notes, the beccafico (plural beccafiche or beccafichi) can refer to a number species of warbler. From Hugh Alexander, History of Fowling, 1897, p. 126:

There is not the slightest question that several small species of insectivorous birds have been regarded as the ‘Beccafico,’ even among the Italians themselves. Thus Francesco Monari observes in his little treatise La Caccia dell Arcobugio, published in 1672: “Certain little birds of many species which are all classed together under the title of Beccafichi, are very good when fat; they arrive in Italy in April and leave in autumn…”

Harold Acton, The Bourbons of Naples, 1957, p. 15.

The passage is on pp. 82–83 (vol. 1) of the English translation and p. 131 (vol. 1) of the Italian original.

Robin Thomas, Palaces of Reason: The Royal Residences of Bourbon Naples, 2024, p. 23. The chapter on Capodimonte can be downloaded here.

Once the renovation is complete a third option will be to start with the famous Battle of Pavia tapestries, a series of seven tapestries designed by Bernard van Orley and woven in Brussels in the years following the February 24, 1525 battle, famous for the Imperial army’s capture of King Francis I of France (he was taken to Spain, where he was held until March 1526). Sadly for me, the tapestries were not on view. They have just completed a three-city American tour (Fort Worth, San Francisco, Houston).

On the provenance of the Bruegels see Jamie Lee Edwards, Still Looking for Pieter Bruegel the Elder, M.Phil(B) thesis, University of Birmingham, 2013, p. 60.

Two other Tüchleins by Bruegel survive, The Adoration of the Kings (Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels) and The Wine of Saint Martin’s Day (Prado).

Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend, translated by William Granger Ryan, 1993, vol. II, p. 213.

“The paper consumption in Florence was already vast by the 15th century.” On Italian printmaking before 1400 see Frans Laurentius and Theo Laurentius, Watermarks 1450–1850, 2023, p. 5.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Italian Journey, translated by Robert H. Heitner, vol. 6 of the Suhrkamp edition of the works of Goethe, 1989, p. 154.

This is great.

Great post! The two Marsyas paintings seem so close, so much in conversation, the Luca Giordano must have been in response to the Ribera--which must have been in Naples, right?

(The Marsyas of Ribera looks like someone by Greco, except of course the head.)