The Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga in Lisbon, Portugal (Part 2)

Portuguese Art and the Art of the Portuguese Discoveries

According to Metropolitan Museum’s online catalogue, its Department of European Paintings holds 1,499 paintings dated 1800 or earlier, out of which 696 are on display.

The remaining 803 are in storage, undergoing conservation, or on temporary or long-term loan. Unfortunately, the website isn’t set up to allow one to select for just these, so if you wanted to see what’s off view you’d have to comb through the full list of 1,499. I’m not curious enough for that. Still, the category of long-term loans interests me—how many such paintings are there? Paintings that belong to the museum and are of sufficient quality or interest to merit display, but that are on view someplace else.

I found one at the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga (MNAA) in Lisbon, a painting left to the Met in 1958 by, to use the laconic words of the MNAA’s wall label, “uma cidadã norte-americana.” The North American citizen in question, Muriel Stokes, had inherited it from her mother, Frances Isabel Ledyard. Frances Isabel was the second wife of J.P. Morgan’s personal counsel, Lewis Cass Ledyard, and the daughter of John Albert Morris, known as the ‘Lottery King’ for his controlling stake in the Louisiana State Lottery Company. In the latter years of the nineteenth century this was the only legal lottery in the United States; when it was banned in 1893 Morris moved operations to Honduras.

For every unanswerable big question in art history (What is the subject of Giorgione’s Tempest? How did Pieter Bruegel the Elder spend his time when he visited Italy in the 1550s?) there are countless unanswerable small questions, questions of little or no import whose answers would satisfy only the idle curiosity of a few eccentrics or pedants. How did an early sixteenth century panel painting of Vincent of Saragossa, patron saint of Lisbon, find its way into the hands of these cidadãos norte-americanos, none of whom seem to have been art collectors? It doesn’t matter, but I can’t help wondering.

In 1962 a Portuguese scholar, judging on the basis of a photograph sent by a Met curator, attributed the panel to Frei Carlos, a Hieronymite friar of Flemish extraction who was one of the preeminent painters of early sixteenth century Portugal. Which leads me to another small mystery: once the Met knew what it had on its hands, why was this work never used as a pretext for a small exhibition? Especially after the death of Salazar in 1970, wouldn’t a little show on early Portuguese painting, with loans from the MNAA, have been in order? Or was this Saint Vincent even on view then? Perhaps not; perhaps he was buried in storage, an afterthought in those years before the centering of the periphery.

No little show ever took place. Instead, in 2013, the Met sent the painting to the MNAA.

Maybe the curators didn’t think much of it? Is my attention here an instance of the soft bigotry of low expectations? Frei Carlos, a good enough Flemish painter for Lisbon, but how would he have measured up in Bruges or Ghent? Is this an artist in the league of Hans Memling, Hugo van der Goes, or Gerard David? For that matter, can he be compared to Juan de Flandes, another northerner who ended up in Iberia, in his case working for the Spanish court?

If the answer isn’t yes, it’s close enough. These are fine paintings. Vincent, wearing a resplendent dalmatic, holding in his right hand a model of the ship that carried his remains to Lisbon in 1173—or not exactly, since it’s a carrack, and there were no carracks in 1173. A martyr’s palm and a closed book in the other hand. Vincent’s cool demeanor resembling (anticipating?) the nonchalant saints of Zurbáran, equally unscathed by their tortures and just as well-dressed.

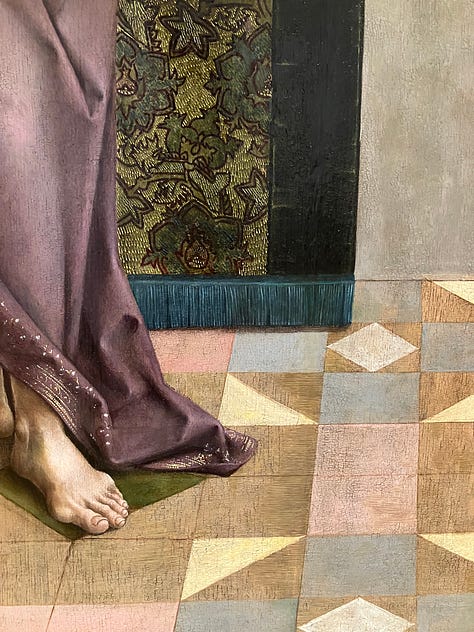

Another painting by Frei Carlos, The Good Shepherd, a work of patterns, shapes and symmetries. Two porphyry columns half seen, a damask backdrop, triangles and diamonds of pale yellow on the tiled floor; and against these the irregular folds of the purple robe, the cradled animal, Christ’s benevolent gaze out at wayward humanity.

And The Calvary Triptych, its left panel an ideal subject for a Hieronymite: Jerome delivering the rule to Saint Paula and her companions. In the foreground, holding a pair of spectacles, Paula of Rome, the first nun, a wealthy Roman noblewoman and the sponsor of Jerome’s Vulgate; beside her, her daughter Eustochium, for whom Jerome wrote his Treatise on Virginity; in the background, monks peering in through a doorway. For us it’s a chance to see how Frei Carlos furnishes a room. Above the monks a little sculpture in a niche; to the side an altar on a platform of pink stone; behind the altar, in a Gothic frame, a painting of the Holy Family.

I asked, in the first part of this review, “Can you name a Portuguese painter from any period?” Now you know one. Maybe. While it is thought that Frei Carlos was born in Lisbon to Flemish parents, all that’s sure in his biography is that he joined the Hieronymite Order in 1517, and died in 1540.

*

Robert C. Smith, in his 1968 survey of Portuguese art (even now the only readily available book in English on the subject) remarks of the foreign artists who worked in the country over the course of three centuries that they lacked “…the qualities necessary to foment a great school of national painting in Portugal.” Nor, according to Smith, did such a school emerge organically. Instead, bracing in his willingness to call the periphery peripheral, he describes Portuguese painting as “in essence a pool of pleasant mediocrity.”1

But he grants two exceptions. The first is Nuno Gonçalves (c. 1425–c. 1491), known for the Saint Vincent Panels, six crowded paintings with sixty figures altogether, portrayed against a dark background. Saint Vincent appears twice, occupying the center of each of the two largest of the six, hence the group’s name. The surrounding fifty-eight figures, some identifiable, serve as a gallery of fifteenth century Portuguese society. The royal family is there, including Dom Afonso V, known as ‘the African’ for his Moroccan conquests, and his uncle Prince Henry the Navigator, sponsor of the voyages down the coast of West Africa that allowed Portugal to bypass the old Saharan trade routes. There are also Cistercian monks, Jews, soldiers, and even fishermen. For Smith, these figures, taken together, express the national character.

“They are proud, intense and strong-willed people, individuals of profound convictions and will to do, who were already caught up in the epic task of projecting their small nation beyond the seas, a task which was to reach fruition a half century later.”2

One wonders, reading these words, if art historians, too, were once proud, intense, strong-willed, caught up in an epic task. And if more has been lost in spirit than has been gained in scrupulousness, now that no one feels comfortable (or capable?) of making this kind of sweeping generalization. Sweeping generalization—I am tempted to replace ‘sweeping’ with ‘sublime.’

So why do we hesitate? That the task was epic cannot be disputed. Pessoa speaks of “those demigods, whose boldness carved more and longer paths through the sea and discovered more land than we could grasp.”3 The problem, at least for me, is how to be sure of seeing it in a painting. However strong and solemn the figures in the Saint Anthony Panels, does one not find a comparable strength and solemnity in the portraits of Rogier van der Weyden, who worked not in Lisbon but in Brussels? And if so, isn’t it likely that what impresses Smith about these men is characteristic not of a place, but of a time?

These men—Smith (carried away by lusophilia?) fails to note something that would jump out at many of us in the twenty-first century: just two of the fifty-eight characters surrounding the pair of Vincents are women. Both have been identified as queens. Standing, in a white veil, is Eleanor of Aragon, queen of Portugal from 1433 to 1438, and then briefly an unpopular regent during the minority of Alfonso V. Kneeling below is Isabel of Coimbra, first cousin and first wife of the same Alfonso. They married at fifteen; it was a love match. She died at twenty-three.

The paintings were once part of a larger ensemble installed in Lisbon’s cathedral, but, eventually outmoded, this was replaced by a new Baroque altar. In 1742 the Saint Vincent Panels were taken to the Palace of Mitra outside Lisbon. There, unlike the replacement altar in the cathedral, they survived the earthquake of 1755.

Since 2020 they have been sequestered in a conservation studio visible through a plexiglass wall. I saw them, or at least five of the six, from a distance. They should be back in the galleries soon.

*

As for Baroque Portugal, Smith enthuses over its gilt wood church interiors and ceramic tiles, but is otherwise dismissive of the period. In addition to the toll on the country taken by a costly war with Spain, he observes that “…the Holy Office of the Inquisition acted as a relentless watchdog to stamp out in painting and sculpture the slightest suggestion of levity or sensuality.”4

A point in favor of the contention: the seventeenth century painting that’s most likely to interest the foreign visitor in this wing of the MNAA is not a dramatic scene by an unsung Portuguese counterpart to Caravaggio or Velázquez, but a portrayal of one of Lisbon’s suburbs, the 1657 View of the Monastery and Square of Belém by Felipe Lobo. Belém is down from the city center at the mouth of the Tagus. Everyone goes there for a pastel de nata and to admire two monuments in the Manueline style, the massive Hieronymite Monastery, long the burial site of Portuguese royalty, and Belém Tower, a fairytale structure that stands just off the shore, lapped on all sides by waves and with the open sea beyond. In its time it defended Lisbon, but it was also, from the beginning, a monument to the Portuguese voyages. Sculpted nautical rope is one recurring motif, and Ulysses, the rhinoceros who inspired Dürer’s woodcut, is carved into one of its turrets. Ulysses arrived from India in 1515, while the tower was under construction.

Not that you can see any of this in Lobo’s painting. The tower is little more than a smudge on the horizon. In the foreground an assorted crowd surrounds a fountain. Two men haul a basket of fish; women fill red urns with water; a man with a sword flirts with woman holding a paper fan; an African woman carries a basket on her head. The monastery rises behind at right, solid, not quite looming. The painting is hardly a major work of art, but it’s an amusing one, and a natural for tourists because, while Belém has changed, it’s still recognizable. The monastery deteriorated after the Hieronymites were expelled in 1833, but this neglect was soon reversed, as restorations were undertaken in the years leading up to the quadricentennial of Vasco da Gama’s arrival in India in 1498. Inside, a neo-Manueline tomb was built for the explorer’s remains.

For those who go the MNAA first, as I did, and then continue south to Belém for a pastry, after the painting the real thing is in one way a letdown. You can no longer see the water or the tower from this vantage point. Instead: a park built for the 1940 Portuguese World Exhibition, the concrete buildings of the Belém Cultural Center, and, between these and the water, eight lanes of traffic and a commuter railway. I was too late, perhaps by a century and a half, for the beguiling simplicity of Lisbon’s outskirts as seen in the painting.

*

I said above that Smith in his study of Portuguese art allowed for two exceptions to his characterization of the national school of painting as “pleasant mediocrity.” The first was Nuno Gonçalves in the fifteenth century; the second is Domingos António de Sequeira (1768–1837), whose career bridges the eighteenth and nineteenth. He has this and much else in common with his near-contemporary Francisco de Goya. Like Goya, Sequeira witnessed the Peninsular War, and like Goya, Sequeira’s late work belongs to the Romantic movement. As for differences between the two, Smith is characteristically grandiose.

…Goya was a profound pessimist, Sequeira a triumphant optimist. His paintings breathe a serene security based on abiding conviction of the future, as well as a lyric joy in mankind and a gentle and confiding faith. Here once again are tellingly restated the spiritual differences between Spain and Portugal which through the centuries have so significantly distinguished the art of the two Iberian nations…”

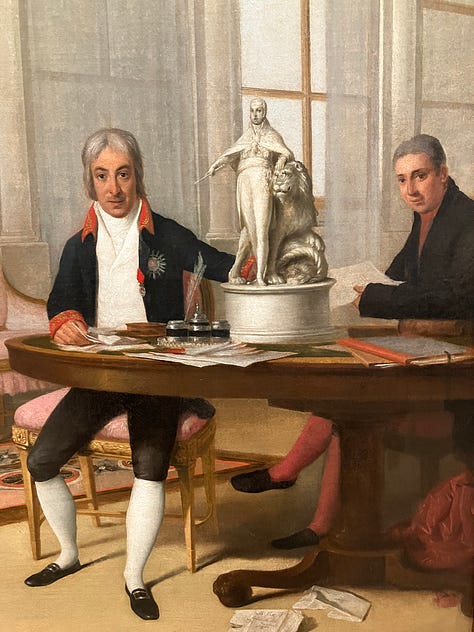

Unfortunately I’m not qualified to weigh in here, either on Iberian spiritual distinctions or on Sequeira. I had not heard of him when I went to the museum, and I didn’t figure out who he was while I was there. In the gallery where half a dozen of his paintings hang I looked closely at only one, the 1816 Family of the First Viscount of Santarém. It’s an appealing group portrait set in an airy, Neoclassical interior, with ten figures spread across the foreground and three more in the painting within the painting on the back wall. The viscount (full name: João Diogo de Barros Leitão Carvalhosa, First Viscount of Santarém) sits at a table with his brother, the Archbishop of Adrianapolis.5 Between the two men, at the center of the table, is a small statue of Dom João VI, who with the rest of the Portuguese court had fled to Rio de Janeiro in 1807, days before Napoleon’s army crossed into Portugal. João was regent at the time due to the madness of his mother, Dona Maria I; he assumed the throne while in exile and returned to Lisbon only in 1821.

To the viscount’s right are his second wife and the couple’s five children, arranged in such a way that the figures in the painting on the wall appear to be part of the group. These latter three are, from right to left, the viscount’s sister, her husband (another viscount), and the viscount’s son from his first marriage (full name after his father’s death: Manuel Francisco de Barros e Sousa de Mesquita de Macedo Leitão e Carvalhosa, Second Viscount of Santarém). They are on the wall rather than in the room because they left with the court in 1807. While in Brazil the viscount’s son took an interest in early Portuguese navigation, and this became a lifelong passion. After his return to Europe in 1819 he wrote extensively on the history of cartography, and also, in spite of being forced out of Portugal for his royalist sympathies after the liberals won the civil war of 1832–34, advocated for his country’s colonial rights, publishing from his Parisian exile (at 47, rue Blanche) works such as the 1855 Demonstração dos direitos que tem a Corôa de Portugal sobre os territórios situados na costa Occidental d'Africa, entre o 5.º grau e 12 minutos e o 8.º de latitude meridional. If ever a man was made for a bit part in Balzac’s Comédie Humaine, it was this Second Viscount of Santarém. I hope he’s in there somewhere.

I liked this painting the moment I saw it, and I like it all the more now that I’ve looked closer at the pictures I took of it and sorted out the relationships between the figures. But I’m not sure it expresses the optimism that Smith finds in Sequeira. For that it’s probably better to look at works like the 1810 Allegory to the virtues of the Prince Regent João, at the Palace of Queluz in the Lisbon suburbs. It’s a bit much after the elegance and restraint of the group portrait; you might even call it preposterous. But I’d like to think that word can be used in a neutral sense, as well as a pejorative one.

*

On to the last part of the museum, devoted to the art of the Portuguese Discoveries.6 There’s plenty of interest in these galleries, but for most visitors the main draw will be the four Nanban screens, painted Japanese screens of the Nanban (or Namban)—that is, of the ‘Southern barbarians,’ mostly Portuguese, who began to visit Japan in the mid-sixteenth century.

It happens that I am not the only person with a Substack to have passed through the MNAA lately. A few months ago Feckless Bellelettrist Marco Roth published Japanese Screens and Grecian Friezes, in which he considers how Walter Benjamin’s famous dictum about documents of civilization and barbarism (is ‘dictum’ the right word? I am tempted to call it a ‘quip’) might or might not apply to the Hellenistic Pergamon Altar in Berlin and to the Nanban screens at the MNAA. I won’t say more; this is a spoiler-free space. So read Roth, and I’ll turn instead to three objects from Portuguese India.

First a painted chest of jackfruit wood, made around 1600 in Cochin (now Kochi). Such chests, most often packed with silk or cotton cloth, were loaded into the hulls of carracks bound for Lisbon.

Cochin was Portugal’s first colony in India, and it was where Vasco da Gama died in 1524, but after the colonial capital was transferred to Goa in 1530 it settled into secondary status. When this chest was made at the turn of the seventeenth century Cochin was home to an estimated five hundred Christian families, as against two thousand in Goa. (Women were forbidden to join the Portuguese voyages, so men who settled in Portuguese India married locally.)

Even as a second city it would have been a busy place. Thousands of these chests must have been made in Cochin. Is this one unusual, or did they often feature interior lids painted with carracks on a smooth sea, with leaping fish, with humanized sun and moon sharing the sky with the cross of the Order of Christ? Maybe not an unanswerable question, but my cursory inquiries led nowhere.

*

Goa, as capital, was the seat of the governor or viceroy of the Portuguese State of India, a territory whose jurisdiction included, in addition to the Indian colonies, Macao, Timor, Malacca, Ceylon and Mozambique. From 1554 to 1695 its governors and viceroys—the title depended on whether or not a governor was a member of the nobility—lived and worked in a large palace on the bank of the Mandovi River. It was less a single building than a complex, including state rooms, a treasury, a chapel, a veranda for public appearances, offices for clerks, a service wing, several patios, a jail. One room looked out onto the Mandovi and whatever fleet had arrived; the walls of another were painted with images of all the ships that had sailed to India from Portugal since the time of Vasco da Gama, including the ones that had sunk on the way. Each was labeled with a number, a date, and the name of its captain. Nearby was the audience room, hung with panel portraits of the governors and viceroys.7

The earliest portraits seem to have been the work of Gaspar Correia (1492–c. 1563), also the author of the illustrated chronicle Lendas da Índia. A local assistant painted the faces. A number of these paintings, or perhaps they are seventeenth century copies after deteriorated originals, are preserved (in an over-restored state) in Goa’s Archeological Museum. And there are two at the MNAA, both in good shape. They portray Dom Francisco de Almeida, the first viceroy, who served from 1505 to 1509, and, his successor, governor Afonso de Albuquerque, the man who sent the rhinoceros to Lisbon in 1515.

Almeida and Albuquerque, in their extravagant costumes, their lordly poses, and the crude, flat technique of representation, remind me of a favorite genre, the Sarmatian portraits of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Around the same time the Portuguese were setting up their far-flung empire, Polish noblemen convinced themselves that they did not share the Slavic ancestry of the peasants they ruled over, but were instead descended from Sarmatians, a Persian steppe people who according to legend had conquered Eastern Europe in ancient times. In the centuries that followed this idea developed into an ideology, Sarmatism, with a corresponding style of presentation and dress. The museums of Eastern Poland (and, I imagine, Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine) are full of paintings of seventeenth-century noblemen in full Sarmatian regalia. Now that I’ve been to the MNAA they seem not so much Asiatic as the distant cousins of the governors and viceroys of Portuguese India. Look for them next time you’re in Krakow, Tarnów or Sanok.

Robert C. Smith, The Art of Portugal 1500–1800, Meredith Press, 1968, p. 195.

Smith, p. 197.

Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet, translated by Margaret Jull Costa, Serpent’s Tail, London, 2018, p. 141 (no. 159, Cenotaph).

Smith, p. 20.

I was confused about this title, as Adrianapolis is the name of the Byzantine city that is now known as Edirne. It’s in the European part of Turkey, near the three-way border with Greece and Bulgaria. How, I wondered, could someone in Lisbon—but it turns out archbishop of Adrianapolis is a ‘titular see.’ That is to say, it’s an honorary, non-pastoral title granted in reference to a diocese or bishopric that no longer exists.

I have left out of my account the galleries of Portuguese decorative arts, as well as (reluctantly!) the Baroque and Rococo presepios (nativity scenes). The textile rooms were closed.

For this section I drew on “The Palace of the Viceroys in Goa” by Pedro Dias. It appears in the exhibition catalogue Goa and the Great Mughal, edited by Jorge Flores and Nuno Vassallo e Silva, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon, 2004, pp. 68–97.

An entertaining ramble. Could use a bit more proofing. One change you'll need to make: 2nd paragraph, second line, "only" should be "any of," it seems.

Is Salazar the Portuguese scholar who made the Frei Carlos attribution? I wonder if it's the same Salazar who did valuable archival research on Ribera.

I liked "centering of the periphery."

I agree that art historians were more adventurous before today's scrupulosity set in. They were unabashedly opinionated & sometimes even shocking in their declarations on art.

Longhi, Berenson & Gombrich come to mind, but I've read others.

I don't know where you find time to do all this but I'm happy you do because you are fun to read.

From me, Deborah.