In town for the annual conference of the Renaissance Society of America, the last thing I wanted, after a long Thursday of listening to panel talks at the Boston Marriott Copley Place, was to spend the evening looking at old European art. I was in the mood to be in a museum, in the mood not to talk or to listen, but to stroll and look, just not to look at anything made in Europe, not to look at anything I might ever do research on.

As if its hours had been arranged to satisfy this desire, the Museum of Fine Arts is open until ten, not just on Thursday evenings, but on Friday evenings, too. So I knew that I could dawdle as much as I liked in the non-Western galleries on my first visit, because there could also be a second one. Maybe I would be more in the mood for the Renaissance and its successor centuries then.

And that’s how it went. As well as an afternoon there in December 2021 I have now had two full evenings at the museum, enough time to wonder if the MFA should be a little more cherished than it is. It drew just under a million visitors in 2024. Meanwhile the numbers for the Met and the National Gallery of Art were, respectively, 5.3 and 3.9 million. MoMA had 2.7 million, and then the Getty and the Art Institute of Chicago 1.3 million each.1

It may in part be that no one likes to visit Boston. I suppose it must be pleasant in the summer, but I’ve only ever been in weather that was drab or worse. It’s out of the way in the corner of the country. It’s expensive; the food is mediocre; the locals are sullen. You go there if you have to. On top of this, the other museums I mentioned are, in one way or another, self-evidently magnificent. Isn’t the public right to prefer the Met, the National Gallery, MoMA, the Getty, and the AIC? Aren’t these our world-class institutions, and isn’t the MFA a shade below that standard? Let’s see.

*

Apart from the ancient grave goods, Asian art, in American museums, tends to be displayed in rotations. The obvious reason for this is sensitivity to light, but it’s also the case that the collections are vast, and compared to other departments exhibition space is limited. Even with two large galleries closed for renovation, the MFA has a quarter of its 1,460 pre-World War II European paintings on view, and the numbers for American paintings are similar. In both cases you can count on being able to see the most famous works whenever you visit, unless they’re on loan or undergoing conservation treatment.

The situation for Asian art is very different. Again using 1939 as the cutoff, out of the MFA’s 5,511 Asian paintings, just 46 are currently up. That’s under one percent. The museum thus has no way to give the casual visitor a sense of the depth of its holdings. In the case of Japanese art, the collection is considered the finest outside of Japan, but you probably wouldn’t know it from the five Japanese galleries.

This means you could probably go once or twice a year for the rest of your life and rarely or never see the same works; whether that’s a positive or a negative thing depends on what you want from a museum. I like the idea that whenever I return to Boston I’ll find something new here, but I hate the thought of not getting another look at the white cockatoo painted by Itō Jakuchū (1716–1800).

It turns out that Jakuchū—I had not heard of him—is one of the best-known and loved of Japanese artists. In 2011, to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of the city of Tokyo’s gift of cherry trees for Washington, DC’s Tidal Basin, the thirty hanging scrolls that form his series, Colorful Realm of Living Beings, was sent from the Museum of the Imperial Collections in Tokyo to the National Gallery of Art.

Now I know: Jakuchū, who grew up in the market district of Kyoto, the son of a grocer, was the greatest painter of chickens ever to walk the earth. According to the epitaph written by the Buddhist monk Baisō Kenjō (1719–1801), Jakuchū, when a young man contemplating his future as an artist, thought to himself:

“…the figures of Chinese antiquity are no longer. And I could not possibly bear to depict Japanese figure subjects. As far as scenery that can actually be seen, I have never encountered anything worthy of depiction. Only flora and fauna are left. However, it is not as if one can regularly observe peacocks, kingfishers, cockatoos, or pheasants. Chickens, on the other hand, are raised in the villages, and the color of their plumage is beautiful. I will begin with them.” Henceforth Jakuchū raised dozens of chickens in his own yard and spent several years observing their forms and sketching them from life. Afterward he expanded [his subjects] to all manner of grasses and trees, birds and beasts, fish and insects, exploring to the fullest their formal appearance and inner essence, until his brush moved as his heart commanded.2

Looking at the works that comprise the Colorful Realm—its fish, insects and reptiles, pheasants in snow, sparrows and millet, maples and songbirds, roses and songbirds, and peonies and songbirds, the claim that he found the inner essence of his subjects seems just. Not for Jakuchū the taxidermical poses of John James Audubon or the clinical touch of Albrecht Dürer. Those artists studied animals; Jakuchū got to know them.

Unlike the fauna of the Colorful Realm, this bird is a pet. Native to Eastern Indonesia, white cockatoos had a long history in East Asia as cherished exotics. Even during the centuries when Japan was nearly closed to the world, the occasional cockatoo was brought to Nagasaki. Jakuchū seems to have been the first artist to paint them regularly. And he worked fast. The Confucian scholar Minagawa Kien wrote in a poem that Jakuchū obliged in a single day his request for a cockatoo painting. Kien was pleased with the result: “the white of the wings is so bright that they seem about to move. There is divinity contained in it, which shines through from the back.”3

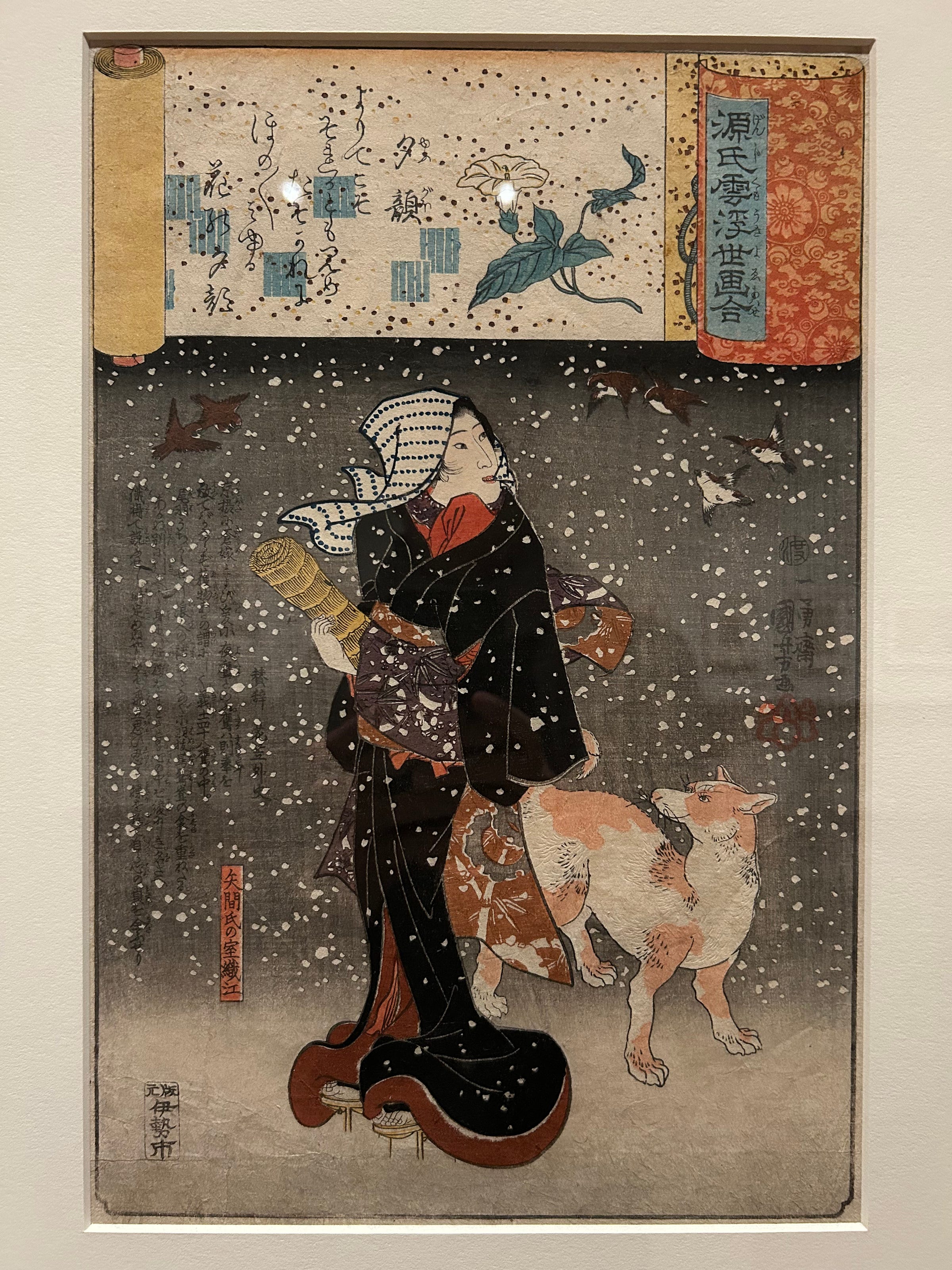

So perhaps my initial worry was misplaced, maybe the Cockatoo is among those works in the MFA’s collection that are brought out more than once in a while, and I’ll see it again. It seems less likely that I’ll have a second encounter with Ichiyusai Kuniyoshi’s Yūgao: Yazama's Wife Orie. The MFA has 45,000 Japanese prints, of which 3,000 are by Kuniyoshi, a nineteenth century painter and printmaker whose name, like Jakuchū’s, I didn’t know. Should I have known? Maybe, but I’m suspicious of the concept; who is to say what anyone should know? In any case, I’m glad to know now, and also glad to have discovered the Kuniyoshi Project, a website of appealingly archaic design devoted to cataloguing his prints.

The Yūgao image is part of a series inspired by Lady Murasaki Shikibu’s eleventh century novel, The Tale of Genji. In the mid-1840s Kuniyoshi made a print for each of the novel’s fifty-four chapters. Rather than portraying events from the novel, Kuniyoshi found scenes from later centuries that parallel or parody its action. Yūgao (‘The Lady of the Evening Faces’) is the title of the fourth chapter, in which Prince Genji, on his way to visit his former nurse, meets an elegant, mysterious woman who lives in a dilapidated house surrounded by moon-flowers. They arrange an assignation at a rural palace, where the woman dies suddenly, victim of an attack by the spirit of one of Genji’s former lovers.

Kuniyoshi’s ‘evening face’ is Orie, the estranged wife of Yazama, who was one of forty-seven samurai whose master was forced to commit seppuku in April 1701 after he assaulted a court official who had insulted him. The forty-seven, now lordless samurai, or rōnin, avenged the honor of their master by killing the official, or rather forty-six of them did, as one was sent as a messenger to report the deed. There was little tolerance for vengeance killings in Edo Japan, so the men expected to be put to death, but an upsurge of popular support persuaded authorities to permit the forty-six (the messenger was spared) to die instead by seppuku, which they did on March 20, 1703. Within weeks, the events became the subject of a Kabuki play, and ever since have remained a favorite subject in Japanese drama and visual arts.

During the interval between the seppuku of the master and the revenge of the forty-seven rōnin, Orie worked as a prostitute. In Kuniyoshi’s print she is seen walking the street on a snowy night, accompanied by a large dog and holding a rolled-up straw mat. Half a dozen tree sparrows are flying around her, in poses that remind me of Giotto’s somersaulting angels in the Scrovegni Chapel. Above is a scroll with a moonflower and a poem.

By coming closer

Might you see, indeed, what face

That flower may have,

Whom in the glimmering of dusk

You glimpsed so faintly faint4

Buyers of the print would have known from a Kabuki play, The Loyal Samurai, that Orie is about to have a chance encounter with her husband, which both of them will recognize as their last. But what does this Orie have to do with the mysterious woman in the Tale of Genji? If you don’t quite get it, you aren’t alone. According to the catalogue of an exhibition of Genji-related art held at the Met in 2019, Kuniyoshi excelled at creating such puzzles—“a bit of cogitation will allow connections, however tenuous, to be made.”5

*

Both of these works, the painting and the print, came to the MFA from the collection of William Sturgis Bigelow (1850–1926), the son of Harvard surgery professor Henry Jacob Bigelow. The younger Bigelow started out on his father’s path. After receiving a degree in medicine in 1874 he went to Paris to continue his studies, but quit them when his father opposed his ambition to pursue a career in bacteriology rather than surgery. Back in Boston, Bigelow attended lectures by Edward Sylvester Morse, a zoologist who had taken an interest in Japanese archaeology when visiting the country to research brachiopods. Morse’s lectures seem to have been a cultural coup de foudre for the young medical dropout. Bigelow accompanied Morse to Japan in 1882 and stayed there for seven years. Following his repatriation in 1889 he donated more than 75,000 works of Japanese art to the MFA. An early Western convert to Buddhism, he was said to have “returned to Boston, full of Buddhist lore, believing he had been aware of his former incarnations.”6 He later sought, by formulating a concept of spiritual evolution, to reconcile Buddhist teachings with the theory of natural selection.7

Bigelow was also a great misogynist. Women were forbidden from visiting his summer retreat on the island of Tuckernuck, next to Nantucket. There was swimming, there was tennis, and there was a well-stocked library, where he would hold court in his kimono for the male luminaries of New England. The main attraction, though, was nudity, which was encouraged (except during dinner). As Senator Henry Cabot Lodge wrote, looking forward to a visit, “Surf, Sir! And sun, Sir! And Nakedness! Oh Lord, how I want to get my clothes off!” Meanwhile Edith Wharton, forbidden from setting foot on this Fire Island avant la lettre, noted of Bigelow that “his erudition far exceeded his mental capacity.”8

*

If I hadn’t known how rich the MFA’s collection of Japanese art is, I would have thought it inferior to the Chinese collection, which is displayed in a somewhat larger series of galleries nearby. On reflection, the main reasons the latter galleries seem more impressive are (i) Japan lacks stone for sculpture; and (ii) Chinese art history starts earlier than Japanese art history. The earliest Japanese work presently on display is a Bodhisattva in cypress from the eighth or ninth century. Several galleries of Chinese art, much of it on a grand scale, predate this.

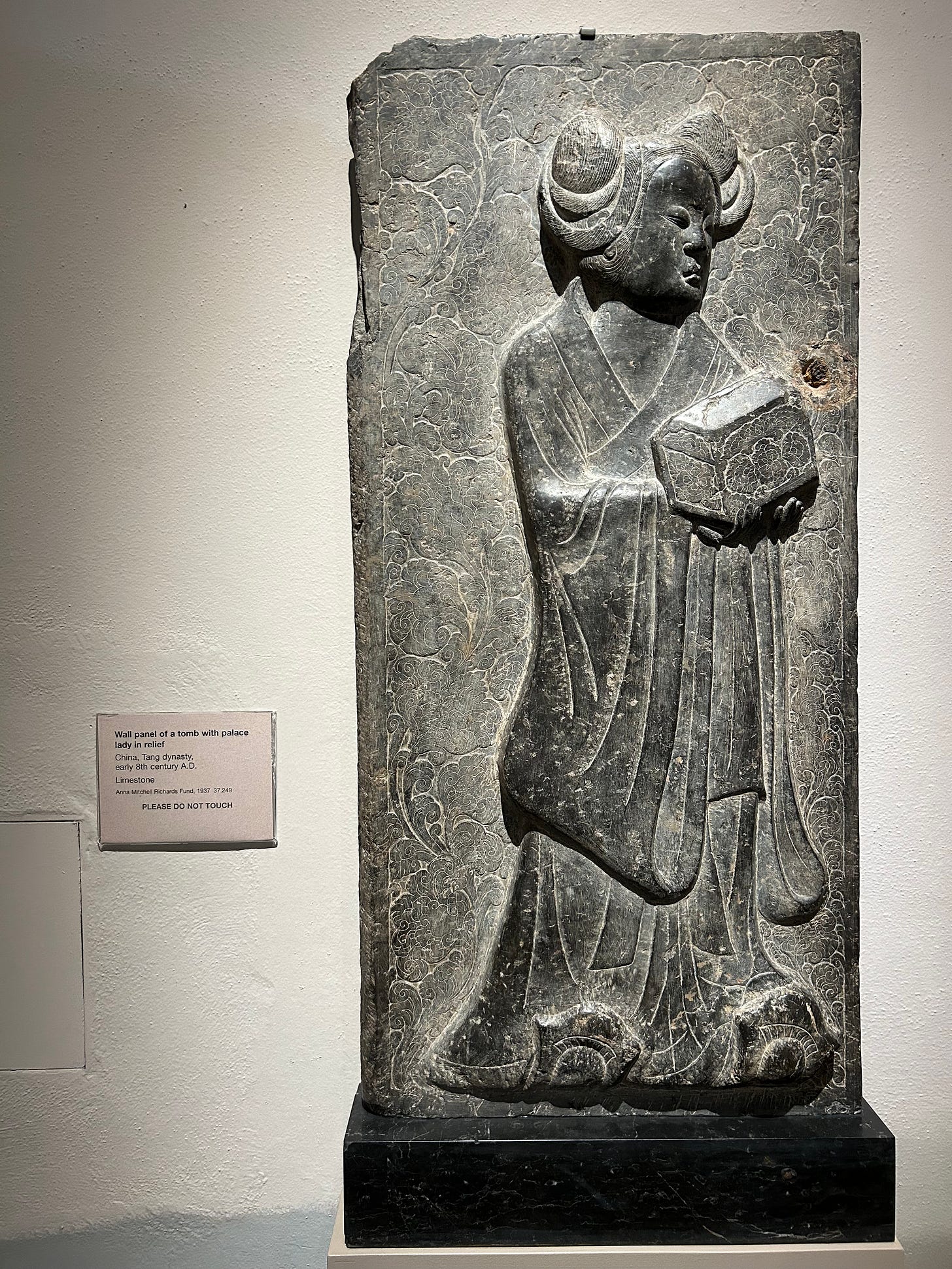

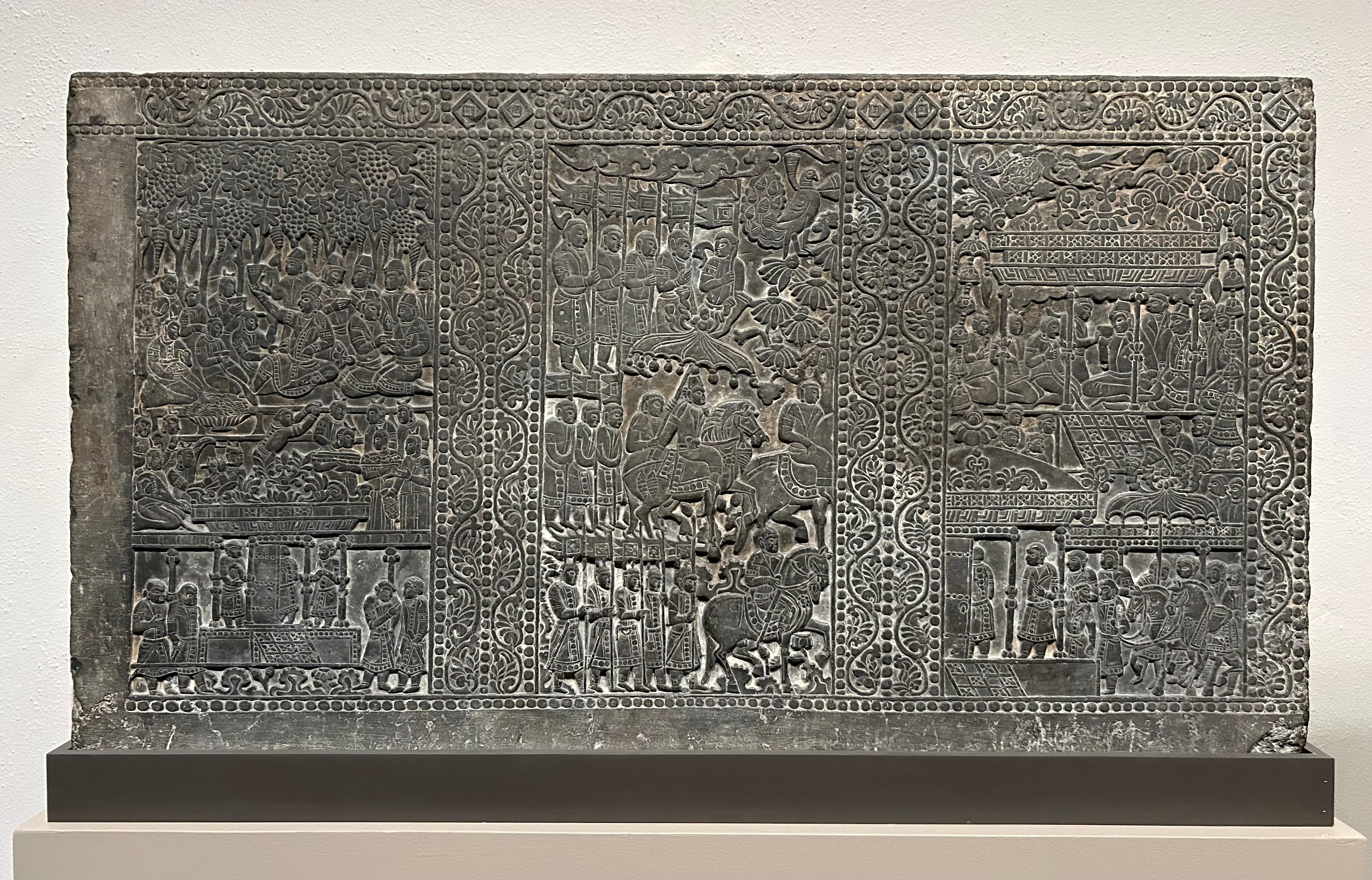

Objects in these galleries have labels, but not much in the way of wall texts, and I am sorry to report that the MFA’s website is not one of the best I’ve spent time with. Many entries lack a catalogue essay, bibliography and exhibition history; some even lack images or provenance. But then, must I prattle on about every object I post a picture of? Maybe not. So I’ll only say two things about the five works below, all of which are from the early Chinese galleries.

Out of the five, only one had a label with text: the tapir-shaped bronze wine vessel (zun) with gold, silver and turquoise inlay tapir. I learned that bronze tapirs have been treasured in China for a millennium, and that the Qianlong Emperor, renowned for his connoisseurship, owned ten such works. The one in the picture does not belong to the MFA, but is on loan from a private collection.

The wall panel relief of a palace lady is one of a pair sold to the museum by C. T. Loo, the legendary (to some, infamous) dealer I wrote about last summer in my discussion of two Tang dynasty horse reliefs at the Penn Museum.

I included the seventh century bullock cart because there are more such carts in a twelfth century painting in an adjacent gallery, Zhu Rui’s Bullock Carts Traveling over Rivers and Mountains. Chinese paintings in museums are difficult to photograph; getting all of this one—it’s forty inches tall by twenty inches wide—into a single picture taken with my phone was out of the question, but the detail below, of a cart pulled by three bullocks (oxen) making a treacherous river crossing, came out with only a few flashes of glare. To get a sense of the painting’s scale you should probably go to Boston, but its precision and misty atmosphere are evident here, though you may have to squint to make out the man holding one of the cart’s wheels to guide it.

Bullock cart paintings, known as panche tu, were a genre in the Northern Song dynasty, a time when the transport of grain from the south over mountainous terrain to outposts on the northern and northwestern frontiers was vital for national security. Some panche tu paintings are inscribed with verses, such as the ones added to another such work around 1500 by the Ming dynasty poet Liu Ji.

[Bullock carts] go up and down hills, a thousand times a day; [they] never leave the side of Taihang Mountain.

The carts are fully loaded with the salt of Wu and grain of Shu [provinces]; the healthy oxen are strong.

Merchants value their goods and profits and are not afraid or tigers; feeding their oxen and sleeping alongside their carts night after night.9

Zhu Rui is a transitional figure; it is unclear whether Bullock Carts Traveling over Rivers and Mountains belongs to the Northern or Southern Song dynasty. The distinction is both confusing and important. The confusion results from the fact that the dynasties are successive as well geographically distinct. The Song dynasty (960–1279), is divided into two periods, with the break at 1127 when the Jurchens, a Manchurian people, invaded and incorporated into their own Jin dynasty the northern Song lands, including the capital, Bianjing (now Kaifeng). ‘Northern Song’ could also be called ‘Early Song,’ since it refers to the period prior to the Jurchen invasion. ‘Southern Song’ could be ‘Later Song,’ because it cover the years from the Song court’s retreat south to Lin’an (now Hangzhou) in 1127 to the Mongol conquest of 1279.

If the painting dates to the Northern Song dynasty, that is, if Zhu painted it before 1127, it depicts a moment when grain transports were of the utmost significance. Without grain, garrison soldiers would not be able to keep the Jurchens at bay. On the other hand, if the painting was made after 1127, it is a melancholy tribute to an effort that ultimately failed.

*

Until it came to the MFA in 2011, the largest classical sculpture in the United States, a colossal marble muse with the head of Juno, thirteen feet tall and weighing seven tons, was in private hands, on the grounds of the Brandegee Estate in Brookline, Massachusetts, just outside Boston. In 1897 Mary Pratt Sprague (later Mary Pratt Brandegee) bought the work from the Ludovisi family of Rome, who had possessed it since at least 1633, the first year it turns up in a Ludovisi inventory (“Una statua colosea due volte del naturale…”). It was sometime in those days—pre-romantic antiquarians being oblivious to the allure of headless statues—that to the body, now thought to have been part of a set of nine muses commissioned for the Theater of Pompey around 32 BC by the future Emperor Augustus, was added a head of the goddess Juno, dating to a century or two later and made of a different type of marble.

In its Ludovisi days the statue was installed at the end of a path on the grounds of the family palace. Archival photographs illustrating an excellent 2013 blog post on the Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi suggest its place was a prominent one, but the Ludovisi property may have been too large for anything to stand out. Nathaniel Hawthorne, at least, failed to take special note of it when when he visited on March 26, 1858.

…[we] wandered among the grounds, threading interminable alleys of cypress, through the long vistas of which we could see here and there a statue, an urn, a pillar, a temple, or garden-house, or a bas-relief against the wall.10

Nor was much made of the Juno-muse after its arrival in Massachusetts. The American archaeologist Richard Norton, who helped to arrange the sale, expected the work’s fame to spread, but the opposite happened—it disappeared into the Brandegee Estate. It seems there is no published photograph of it from the more than a century it was there. And even now, although it towers in its gallery, I doubt anyone would consider it the room’s most interesting object. A more likely choice for that honor might be the so-called Boston Throne, a relief sculpture one of whose three sides is visible on the left in the above picture.

It is thought (by some) that the Boston Throne is Greek rather than Roman, and that it dates to the Classical period of the fifth century BC. It may originally have been a decorative screen for an altar in one of the Greek colonies of Southern Italy. If so, it was later taken to Rome, and dug up in 1894.

In the central relief a winged male figure, standing in the nude, is flanked by two seated women, one weeping and the other pleased. The three are tentatively identified as (left to right) Aphrodite, Eros, and, thanks to the pomegranate at far lower right, either Demeter or Persephone. Cuts in the marble indicate the absence of what once completed the work, a metal scale held in the right hand of Eros. It weighed two men who are seen, their hands bound, in narrow, pyramidal reliefs adjacent to the legs of the goddesses. The one on Aphrodite’s side is the heavier of the two. A persuasive interpretation of the scene has eluded scholars, as evidenced by the conflicting stories told in the wall text and on the museum’s website. According to the wall text, Aphrodite and Persephone are engaged in a contest for Adonis, whereas the website proposes that Aphrodite looks on as Demeter learns that her daughter is fated to spend part of each year in Hades. Another theory: the women are not goddesses at all, but rather two wives, only one of whose husbands will return home (but if that were the subject, the heavier side of the scale should provoke mourning, not the lighter side).

Nor is there consensus that the work belongs to the Greek Classical period. It has also been thought to be Roman copy of a Greek original, or else, as the Norwegian scholar Siri Sande argued in 2017, a nineteenth century forgery. “Hardly a feature,” she observes, “has been free from attack.”11

Unequipped with a connoisseurial scale that would allow me to weigh in on the question myself, I will only note the MFA’s adherence to a principle I have also observed in other museums—the principle of declining to acknowledge, either on wall label or website entry, scholarly doubts about a work’s authenticity.

*

The Met is generally considered to have North America’s premier display of Egyptian art, but the MFA’s collection is bigger in terms of sheer number of objects, and the MFA also has what is probably our single most renowned Egyptian work, Menkaure and his Queen, excavated the Menkaure Valley Temple at Giza temple by a Harvard archaeological expedition in 1911 (the last and smallest of Giza’s three pyramids is Menkaure’s).

“It belongs in a museum”—I took to heart, when I was a boy, the words of Indiana Jones, but in Boston I found myself uninterested in this famous pair, and now I’m wondering if it might not be just as well to see them in a classroom, on a PowerPoint slide. From time to time over the course of a semester I tell my students that we are only looking at photographs on a screen, and that much is lost in the translation. Generally speaking, I believe it, but if it’s true, as it must be, that some works lose more than others, doesn’t it follow that some lose very little?

To be sure, it’s a splendid sculpture—the determined advance, the fixed gazes, the hard greywacke (6 to 7 on the Mohs scale) sculpted smooth, and all this belied by the queen’s gentle touch. But does seeing it in person make a difference? It didn’t for me, though of course it’s also true that of all the objects in the room, it was the only one I was familiar with. How much more interesting to discover another Menkaure from the same temple in Giza, or at least the lower third of him, in alabaster and seated on a throne with hieroglyphs. And nearby, on an adjacent wall, part of a relief from the tomb of a prince, in which a man on a boat is returning from a hunt in the marshes. He has two crates of ducks, caught with the assistance of a decoy heron. This bird, which would have been made of clay, is a reminder, in a room filled with objects made for tombs, that there was more to Ancient Egyptian art than what we can see in our museums. If we don’t have any decoy herons, it’s because they were used rather than buried.

*

Finally, a wooden bowl from the Lozi people of Zambia, on whose lid a man is seated behind six pelicans in two columns of three. He can’t be driving them, can he? An adult pelican weighs about twenty pounds. Could six of them pull a man in a boat? I think not. Still, they seem somehow to be in his charge. Looking around online, I confirmed the existence of pelicans in Zambia (though not their domestication); found more Lozi pelican objects at the British Museum, several bowls, a spoon, and a stool (none of these with a man, though); and learned that waterfowl decorate implements used by the wives of Lozi chiefs (the corresponding animal for a chief is the elephant).

As the MFA’s wall label mentions, Lewanika (1842–1916), King of Barotseland, as the Lozi lands were then known, was both an artist himself and a canny judge of what sort of objects appealed to Western visitors. In 1902 he traveled to London for the coronation of Edward VII (according to his New York Times obituary, which ran on February 16, 1916, he was “one of the most interesting guests”); he also toured England and Scotland. On his return he opened a “native curios store” on the Zambian side of Victoria Falls to sell objects made in the workshops he had set up in Barotseland. This, presumably, is the source of most Lozi art in museums today.

I wanted to write, just now, …to sell traditional objects made in the workshops he had set up… but it’s unclear how traditional any of this was at the time. As Karen E. Milbourne argued in a book chapter in 2013:

…the stereotype of one kingdom’s style appears to have been produced purposefully, in order to make a name for—or promote a vision of—Lewanika and his nation… Lewanika and his successors have, literally, crafted Lozi identity and exported it worldwide.12

ntriguing, but I hoped the word ‘pelican’ would appear in this text. It does not.

Next month: Part 2 on the MFA, European and American art

These numbers come from The Art Newspaper.

Colorful Realm: Japanese Bird-and-Flower Paintings by Itō Jakuchū, by Yukio Lippit, National Gallery of Art, 2012, p. 151 (translation by Yukio Lippit).

Quoted in Colorful Realm, p. 49 (translation from The Paintings of Itō Jakuchū by Money L. Hickman and Satō Yasuhiro, 1989).

Quoted in The Tale of Genji: A Japanese Classic Illustrated by John T. Carpenter and Melissa McCormick, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019, p. 312 (translation from A Waka Anthology, vol. 2, Grasses of Remembrance, by E. A. Cranston, 2006).

The Tale of Genji: A Japanese Classic Illustrated, p. 312.

Fenollosa And His Circle by Van Wyck Brooks, p. 29, 1962.

Buddhism and Immortality by William Sturgis Bigelow, 1908.

The Lodge and Wharton quotes are from “Bigelow and his Tuckernuck Retreat” by Frances Kartunen, Yesterday’s Island, Today’s Nantucket, vol. 37 no. 10, June 28–July 4, 2007. There’s more on Bigelow at Tuckernuck in The comradeship of the "Happy Few": Henry James, Edith Wharton, and the pederastic tradition by Sharon Kehl Califano, doctoral dissertation, University of New Hampshire, 2007, pp. 234–35.

Translation from Paintings of Traveling Bullock Carts (Panche Tu) in the Song Dynasty (960–1279) by Wen-Chien Cheng, Archives of Asian Art, vol. 66, no. 2, 2016, p. 254.

Quoted in The 1858 Visit of Nathaniel Hawthorne to the Villa Lodovisi, illustrated, December 27, 2012, Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi. Original source: Passages From the French and Italian Notebooks, vol. 1 by Nathaniel Hawthorne.

“The Ludovisi “throne”, the Boston “throne” and the Warren cup: Retrospective works or forgeries?” by Siri Sande, Acta ad archaeologiam et artium historiam pertinentia, vol. 29, no. 15, 2017, p. 31.

“Lewanika’s Workshop and the Vision of Lozi Arts, Zambia” by Karen E. Milbourne, Chapter 9 in African Art and Agency in the Workshop, edited by Sidney Littlefield Kasfir and Till Förster, 2013, p. 244.

Truly a spectacular collection.

Another very entertaining & informative piece about a museum.

I've only gone to the Boston MFA to see special exhibitions & with some time left over, have wandered around its painting galleries.

So I'm unfamiliar with the Asian art or much else there.

The Japanese paintings you highlighted are beautfiul.

I should look at them the next time I'm there.

Last time I went was for the Dalì exhibition.

I'm shocked at the low attendance, but then it's never been crowded when I'm there, although the Dali show was pretty busy.

So much art. So little time.

Keep writing.