In the seven years since I last went to Yale University Art Gallery nobody planning a visit asked me what to see there, which is a pity because if someone had asked I would have sent them in search of a painting that doesn’t exist, a still life of lemons by Manet. In my memory it’s a small painting, two or three lemons on a plate or a table against a dark background. Wide brushstrokes of vivid yellow, the sort of thing you’d love to have on your wall in general, but especially on a drab day in February or March.

Ha. There’s a Manet not quite of this description in Paris, at the Musée d’Orsay. One lemon on a plate, the background an intermediate gray-brown. And at Yale? I think I conflated three or even four paintings. First a small Manet with two yellow apples that hangs below a Fantin-Latour of three pink roses in a vase. So the size of the Manet is right, as is the quantity of fruit, but the yellow is pale rather than vivid, and no one would call the background dark. Fantin-Latour, however, gave his roses just the dark background I had in mind.

In the next gallery there’s a larger Manet of a woman in Spanish dress, a variation on Goya’s Clothed Maja. The woman reclines on a piece of furniture the label calls a “tuffeted daybed,” but that’s irrelevant here, what matters is in the foreground—two oranges, one in front of the daybed and the other to its side in the clutches of a black and white cat. The oranges are painted in the rough way that I remembered the lemons, and they’re just as bright, but of course they’re the wrong color.

And finally, in a third room, there’s a small still life by Cézanne, six objects on a table, with the requisite dark background. Two of them are lemons, but these aren’t the Manet lemons I had in mind. They’re dull. You could mistake them for potatoes.

So here’s what I did, maybe. In the process of turning my recollections over in my mind I created a composite. Starting with the Manet still life, I discarded the pale apples, darkened the background in the manner of the Fantin-Latour, inserted the oranges from the other Manet, and turned them into lemons via the Cézanne. The stuff dreams are made of.

*

I also would have mentioned, to the same hypothetical person who asked for suggestions about the Yale museum, the Mithraeum from Dura-Europos. I didn’t see it on my previous visits because it didn’t occur to me to enter the Dura Europos gallery, I must have walked past the door and thought, why would I spend my time with stuff from a dig when I could be upstairs with the paintings? Not that I had any idea what Dura-Europos was.

I learned in the summer of 2022, when I taught an art history intro class for the first time (I wrote about that experience here). Dura-Europos, founded by one of Alexander the Great’s generals around 300 BC, was a town on the west bank of the Euphrates River, about forty miles north of today’s Syria-Iraq border. It belonged in turn to the Seleucids and the Parthians, and then, in the mid-second century AD, was captured by Rome. The Romans held it for about a century, until it was besieged and taken by the Sasanians, successors to the Parthians. Rather than colonizing this border settlement themselves, the Sasanians expelled its residents and left it empty—a sensible decision given how often it had changed hands in the five-plus centuries since its founding. The Dura-Europans fled westward, leaving their homes, administrative buildings and places of worship. No one ever lived there again.

Estimates of the population of Dura-Europos during its Roman years range from five to fifteen thousand. This was no metropolis by the standards of the time—Palmyra, about two hundred miles to the west, had a population of several hundred thousand. Still, thanks to the religious diversity of the eastern Roman Empire, in a way it was cosmopolitan. There were devotees of various Greco-Roman and Palmyrene deities, there were followers of the ancient Persian sun god, Mithras, and there were Jews and Christians.

If Dura-Europos had remained inhabited, over time its second- and third-century buildings would have been redecorated or replaced. That’s what happened everywhere else. It was the expulsion of its population that made it special. If you’re an archaeologist, probably the only thing that beats an abandoned settlement is one covered by volcanic ash.

So there were all sorts of surprises waiting for the the team that excavated the site between 1928 and 1937, a joint effort of Yale and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters. Some of the buildings, including the church, the synagogue and the Mithraeum, were especially well-preserved, because in preparation for the Sasanian siege the Dura-Europans filled them with earth to strengthen the city walls.

Dating to 235 AD, the church of Dura-Europos is the oldest known church, or, properly speaking, house church, which is to say it was a former private house converted for worship. Its decorative scheme is underwhelming, at least to anyone familiar with later examples like the Roman churches of Santa Costanza (fourth century) or Santa Sabina (fifth century). There is no colorful marble, and there are no glittering mosaics. Still, a first is a first. There are older depictions of Christ in Roman catacombs, but these are the earliest ones from a church. Wall paintings decorated the baptistery, the most important part of a house church—they show Christ as the Good Shepherd, Christ walking on water, Christ healing a paralytic. The simplicity of the paintings and of the church as a whole are characteristic of Christianity’s slow start. When this house church was in use, the life of Christ was about as far back in the past as the founding of the United States is today. It is unclear whether the Christians of Dura-Europos worshipped in secret, but even if they didn’t they were a small group.

The synagogue of Dura-Europos was larger and more impressive. Its painted walls were a revelation to scholars of Jewish art, but these were not brought to New Haven. They stayed in Syria and are now in the National Museum of Damascus. What Yale has from the synagogue is a few dozen of the building’s over two hundred surviving ceiling tiles, sixteen of which are on display. Among the tile decorations are pine cones, a sea monster, inscriptions in Greek and Aramaic, a centaur, a goat. The Jews of Dura-Europos were not over-literal in their reading of the Second Commandment.

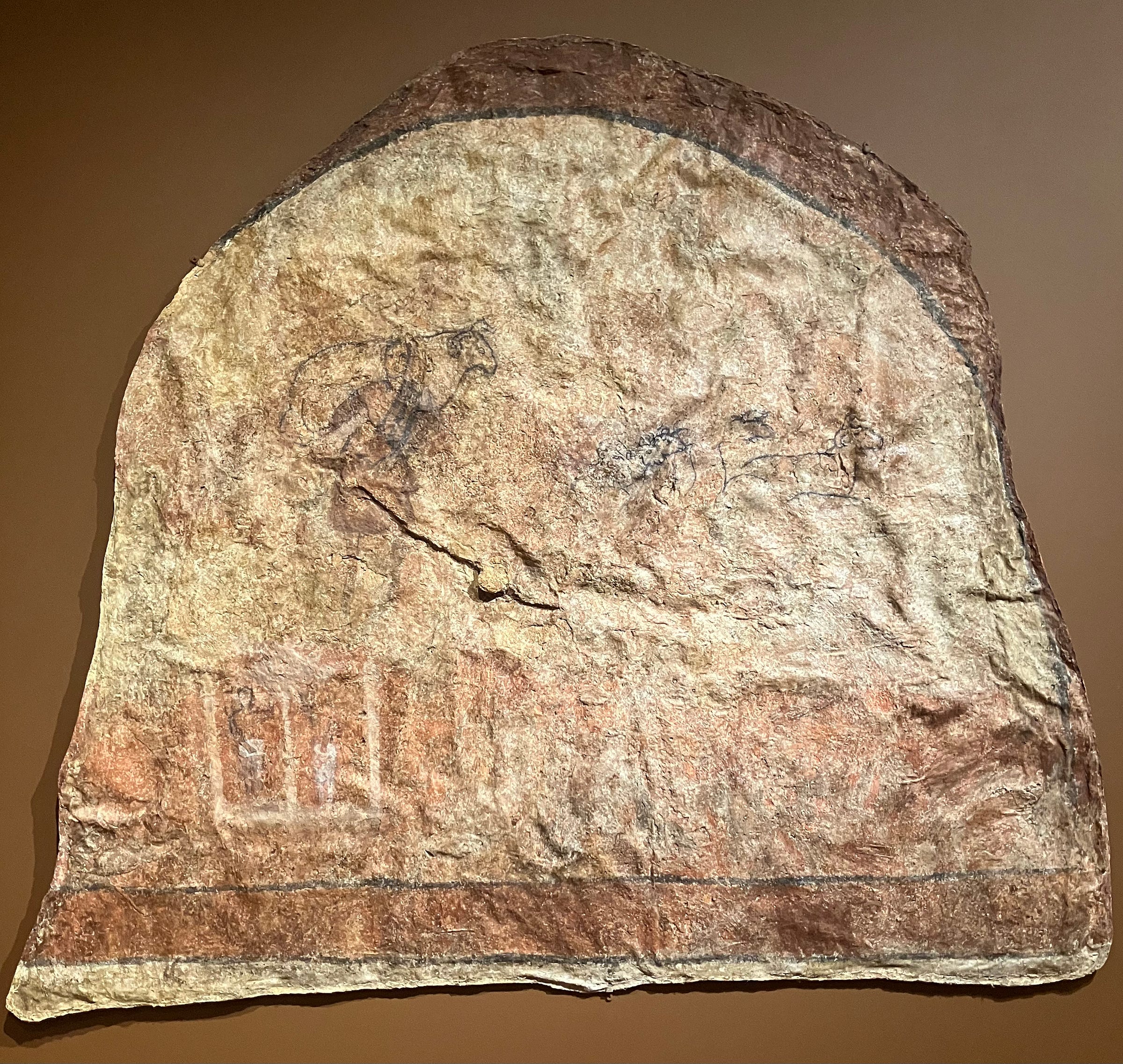

While these Christian and Jewish artifacts are of indisputable historical interest, the most striking of the Dura-Europos objects at Yale come not from religions still around today, but from temples to gods no longer worshipped. Chief among these is the Mithraeum, found in the part of the city that served as the military base. The cult of Mithras was taken up in the Roman Empire during the first century AD, largely but not exclusively by soldiers. Roman Mithraism, loosely based on Zoroastrian concepts, was secretive, involving initiation rituals that are only poorly understood today. Worship seems to have centered around images of the tauroctony, or slaying by Mithras of a sacred bull connected to the life force of the universe.

As well as soldiers, surviving lists of initiates include merchants and minor officials, but no women, and no one too important, at least not in the third century. Elite Romans only began to see the appeal of Mithras during the final decades before the cult was suppressed under the anti-Pagan policies of the Christian emperor Theodosius (r. 379–95).

The Mithraeum of Dura-Europos is unusual among surviving examples for its double tauroctony—two limestone reliefs of Mithras slaying the universal bull, one with inscriptions in Palmyrene and the other with inscriptions in Greek. Both feature the conventional witnesses to the event, a raven, a dog, a snake, the sun, and the moon. The larger of the two also includes a group of devotees looking on.

I doubt these reliefs are anyone’s idea of great art. Even if they retained their original polychromy, and the gold leaf that once adorned the garments of Mithras, it’s hard to imagine being filled with awe by cult mysteries in this setting. Still, whatever rituals were performed here, they would have passed the time, no mean feat in a garrison in the middle of nowhere. A contemporary equivalent might be—I don’t know, maybe a yoga studio in a small town in Lithuania? Not that Lithuania is about to be conquered by its eastern neighbor, its inhabitants put to flight. Not that yoga is a century away from being suppressed by force of law following the widespread adoption of pilates. But suspend your disbelief, and imagine that over time every yoga studio in the world turned into a something-else studio, except for one in Lithuania where a town was abandoned. And then imagine scholars—from where?—your guess is as good as mine—digging it up in another two thousand years, finding laminated pamphlets in English and Lithuanian presenting confused interpretations of esoteric Hindu concepts. And imagine the scholars trying to make sense of it all.

Of course it’s also possible that none of our descendants, two thousand years from now, will be curious about such things, will be curious, for example, about Lithuanian yoga practices. The death of the humanities. No hard feelings, but still, sad to imagine.

*

Every world has its scandals and disasters that reach the consciousness of the wider culture. In the museum world, this might happen when a major museum is accused of possessing of looted objects, when a junior curator accuses a senior curator of racism, or when a pedestal collapses in the middle of the night, shattering a fifteenth-century statue. The last of these instances involved conservators, but in a good way: the statue was painstakingly reassembled, and put back on view a dozen years after its fall. Scandals in which conservators are villains, rather than saviors, are rare, and considering how much can go wrong in a conservation studio, that is for the best.

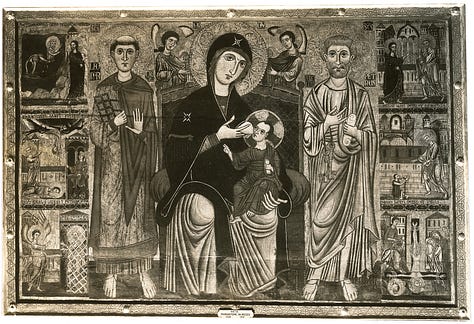

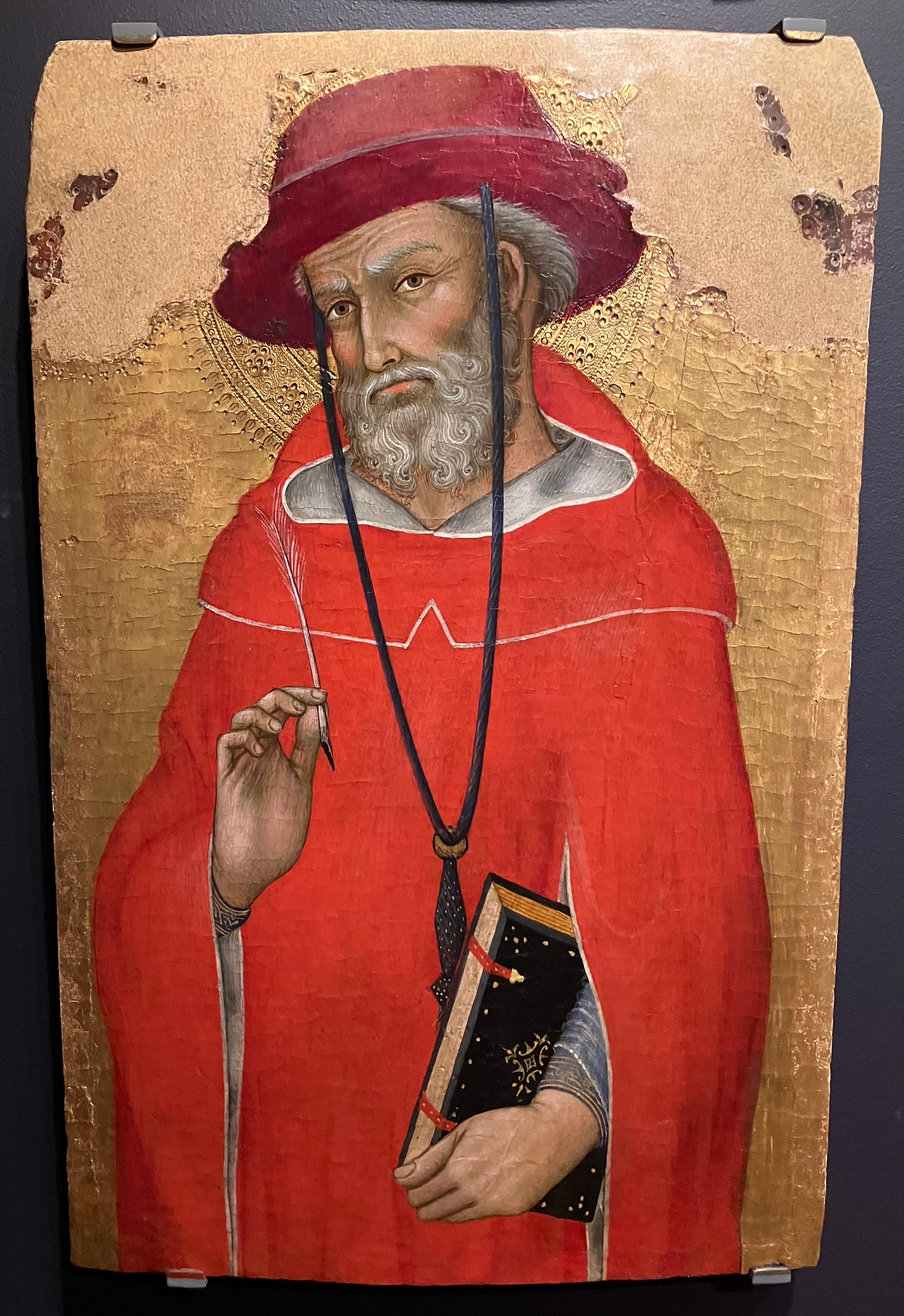

Rare, but not unknown. To fit it to Marx’s pattern of tragedy and farce, if the famously botched 2012 restoration of a fresco of Christ in the Spanish town of Borja was a farce, the radical conservation treatment of Yale’s early Italian paintings from the 1950s to the early 1970s was a tragedy. I’d forgotten the story, in fact I never knew it well, it was only something I heard a professor mention once, but it came back to me with my first glance at the thirteenth century altarpiece by the artist known as the Master of the Yale Dossal. The bare wood in the lower section of the painting, and the fragmented nature of the three scenes on the left—old Italian paintings in other museums don’t look like this. Only at Yale.

Before I get to the conservation debacle, a word about the history of the paintings. Yale is home to the Jarves Collection, an unusually large group of early Italian works, and I can’t resist including a brief account of how the museum came to possess them.

James Jackson Jarves was born in Boston in 1818, second son of Deming Jarves, a glass manufacturer who never made a large fortune but was successful enough that he was later called “the father of the American glass industry.”1 James Jackson was a precocious boy, reading (so he later claimed) Herodotus and Plutarch before he turned eight. But he fell ill at fifteen, and after a few years of unsuccessful treatments doctors advised sending him someplace warmer than Massachusetts. At the time many Bostonians, including the Jarveses, had connections, either commercial, missionary, or both, in the Sandwich Islands, as Hawaii was then known. James Jackson sailed for Honolulu.

He arrived in June 1839, shortly before his nineteenth birthday. After a quick recovery from whatever had been wrong with him in Boston he contracted Hawaii-mania, first convincing his father to invest in a silk business, and then, in 1840, founding The Polynesian, an English-language weekly. The venture must not have kept him busy, for he also, by writing a history of Hawaii that was published in Boston in 1843, fulfilled a childhood dream of becoming a historian. The Polynesian was successful enough that in 1845 Jarves was bought out by the Hawaiian government. He stayed on as editor for a few years after that before heading home disappointed.

Jarves was disappointed because he’d had higher ambitions for his time in Honolulu than writing and editing—he had wanted to make a fortune. Having failed at that, he went to Europe, first to Paris and then to Florence, where he joined the local community of Anglo-American expatriates, read John Ruskin, and remade himself as a critic, connoisseur and art collector. During the 1850s, in addition to publishing Art-Hints, a handbook for aspiring cognoscenti, he spent thousands of his father’s dollars on Italian art, mostly Tuscan paintings of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

Still trying to strike it rich, in the 1860s Jarves took an interest in Italian asbestos, and, hoping to raise money for an asbestos-exporting venture, he returned to the United States to sell his paintings. Unfortunately, his taste was far enough ahead of the mainstream of his time that he was unable to find a buyer.2 Instead, Yale University loaned him twenty thousand dollars, less than half of the fifty thousand he had in mind, with one hundred nineteen paintings as collateral. Two years later, American manufacturers having declined to buy his asbestos, Jarves defaulted on the loan and the university took possession of the collection—perhaps somewhat reluctantly, considering the tone of the promotional material that accompanied its initial display in 1868.

We… hope it may be agreeable to yourself and your friends to take a large share in the pleasure and instruction which this special collection cannot fail to afford all lovers of art, not prejudiced by an exclusive regard to mere technicalities… Of course, the visitor must not look for beauty of execution in all the works of a series intended to exhibit the gradual progress from very feeble, though well intentioned beginnings.3

America eventually caught up with James Jackson Jarves, and Yale learned to appreciate the bounty that had fallen into its lap for a song. So this story would seem to have all the makings of one that ends happily ever after, but many year later, in 1951, Yale professor and curator Charles Seymour initiated a novel conservation program for the Jarves paintings. Over the course of the two decades that followed all restorations, additions and retouchings were removed. This must have seemed like a good idea at the time, and in fact the words sound reasonable enough as I type them now. Who wouldn’t approve of an effort to strip away the work of all later hands, the better to allow the modern viewer to encounter the original artist?

The answer is, pretty much anyone with a sense of how it would go. Here are a few responses to the endeavor.

The tragedy of the Jarves Collection—and it really was a tragedy—resulted from zealously pursuing a methodology: a methodology that sacrificed a concern for the appearance of a work to its documentary value… His [Seymour’s] idealist/modernist position was one that aimed at salvaging the sacrosanct moment of creation from the accumulated interventions of history… The Rule of thumb was: when in doubt, remove it. (Keith Christiansen, The Truth, Half-Truth and Falsehood of Restoration, 2002)

The approach was scientific, not aesthetic. In a medical school, the sort of work that was performed on the Jarves pictures would be reserved for cadavers in an anatomy class, not living human beings. (Richard Feigen, Tales From the Art Crypt: the Painters, the Museums, the Curators, the Collectors, the Auctions, the Art, 2000)

At its most extreme, the practice reduced a handful of paintings to the status of mere curiosities: old pieces of wood with isolated fragments of color clinging to their surface. (Laurence Kanter, The Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin, 2010)

In the Yale Gallery as well as in its new catalogue, the Italian Renaissance pictures—which constitute its glory—are shown as though on the dissecting table.” (Louisa Vertova, The Burlington Magazine, March 1973)

According to a rare, written treatment report from this period, the cleaning solvents that were used on this painting [Gentile da Fabriano’s Virgin and Child] included morpholine, ethylene dichloride, water, and detergent, all potentially harsh gripping agents that we might hesitate to use today on sensitive gold ground paintings. (Mark Aronson, The Conservation History of the Early Italian Paintings at Yale, 2002)

But maybe there is a happy ending, after all. The museum world has a fairy godmother, one institution whose endowment dwarfs everyone else’s. The J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles does not have a conservation department like other museums do. Instead, next door is the Getty Conservation Institute, which employs more conservators than are strictly necessary to care for the museum’s collection and is therefore in a position to take on other projects. In the late nineties Getty conservators worked on a few dozen of the Jarves paintings, including the Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints Leonard and Peter.

More recently, and again with the assistance of the Getty Foundation, Yale published the first section of a new online catalogue of its Italian paintings. The entries include in-depth condition reports, and, in many cases, archival photographs. The Virgin and Child Enthroned can be seen before the Seymour-era treatments, with its centuries of retouchings intact, and then afterwards—as though on the dissecting table—with large sections removed, all the losses visible, and two long, horizontal cracks. The decision to make these images public is to Yale’s credit; setting aside a few obvious instances of deteriorated works (Cimabue’s Crucifixion, Leonardo’s Last Supper), and of canonical paintings that were attacked (Correggio’s Leda and the Swan, the Velázquez to which the suffragette took a meat cleaver), it can be difficult to learn what kind of shape an old artwork is in. If you know, you know; if you don’t, good luck finding out.

A dossal, incidentally, is a single-panel painting that hangs behind an altar. Dossals derived from earlier cloth wall hangings, and were the forerunners of the complex, multi-paneled altarpieces of the fourteenth century, works like Duccio’s Maestà. The central scene of the Yale dossal is a Virgin Galaktotrophousa (‘She who nourishes with milk’), a representation whose origins are both ancient and obscure. The Virgin’s milk was held to represent the salvation of mankind. The presence to her right of Saint Leonard of Noblac, patron of prisoners, is thought to be a sign that this dossal was originally made for the church of San Leonardo in Arcetri, on the outskirts of Florence. Leonard of Noblac (d. 559) was a hermit in what is now the Limousin region of France. Remigius, Bishop of Reims, granted Leonard the privilege of freeing prisoners; some of those he freed followed him to his forest, bringing their chains as an offering. His feast day is November 6.4

*

So it was with the Baltimore Museum of Art, and so it is with the Yale University Art Gallery: I have run out of space, but not of things to say. I’ll close this post with three more Italian works, these from Siena rather than Florence, and write a part two for next month.

For my account of the life of James Jackson Jarves I drew on the Flaubert scholar Francis Steegmuller’s 1951 biography, The Two Lives of James Jackson Jarves.

He was not far enough ahead of his time, however, to admire Caravaggio, as I learned while perusing Art-Hints.

Italian art is remarkable for its absence of humor and love of domestic life, two elements which abound in the German races. It deals abundantly in high life, in its aristocratic forms, in religious topics, human passion, and historical events; it is prolific of classical knowledge and heathen mythology, but it has failed to give us a portraiture of the people. From it we gather nothing of their hopes and fears, their struggles and enjoyments, their actual every-day existence; in fact, it negates their being. Caravaggio is perhaps a solitary instance among Italian artists of repute who has condescended to recognise the wayward humors and fancies of every-day humanity, but with so much coarseness that we can well forgive the rarity of his pictures. (pp. 260–61)

Quoted in Steegmuller, p. 237

There was a man who, upon his return from a pilgrimage to Saint Leonard, was taken captive in Auvergne and locked in a cage. He pleaded with his captors, telling them that since he had done them no wrong, they ought to let him go for the love of Saint Leonard. They answered that unless he paid them a copious ransom he would not get out. He replied: “That’s between you and Saint Leonard, to whom I am committed, as you know!” The following night Saint Leonard appeared to the commander of the stronghold and commanded him to release the pilgrim. This man woke up in the morning, dismissed the vision as a dream, and had no thought of setting the prisoner free. The next night the saint presented him with the same command, and again he refused to obey. On the third night Saint Leonard took the pilgrim and led him outside the fortress, and immediately the tower and half the castle collapsed and crushed many, leaving only the recalcitrant chief, whose legs were broken, to welter in his own confusion.

From the ‘Life on Saint Leonard’ in The Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine (William Granger Ryan translation, vol. 2, pp. 245–46)

You're such a great storyteller. The well-researched asides are fun and informative, adding depth to your museum reviews. I especially liked the quotes you dug up regarding the issue of restoring damaged artworks, to what level of finish should it be taken? I remember in Philippe's class Ars Brevis that he covered that issue. Keep writing!