In June 2021, a few days after the EU reopened its borders to Americans, I went to France for my first long trip away from New York since 2005.1 Two months in Marseille and then a shorter stay in Paris. I was writing my dissertation at the time, so in a way it was a change of scenery rather than a summer of travel. I spent most of my Marseille days sitting with my laptop in my Airbnb until late afternoon or early evening. Then I’d take a walk, maybe buy groceries or have a drink.

That was most days, but I made time to see the sights of Marseille and to go to the beach a little. And I took day trips—to Montpellier, Avignon, Arles, Aix en Provence (twice) and Nice. I regret not going to Toulon, and I regret not making a second trip to Arles, but on the whole I made good use of my time.2 When I landed at Newark Airport in September the end of my Ph.D. was, if not on the horizon, just beyond it. I did the defense the following April.

I mention all this because of something that happened the day I was in Nice. I like going to museums, walking through galleries, stopping in front of this or that, reading or ignoring a label, taking some pictures, having coffee, seeing what’s in the shop, and then revisiting the experience in daydreams or (now) Substack essays. These are all pleasures, but I will be the first to admit they are mild pleasures. Even standing in front of a large and exciting painting one’s experience is pretty intellectual, more thoughts than feelings.

This is the case not just nine times out of ten, or ninety-nine times out of a hundred, but pretty much always. I could keep going to museums for the rest of my life and only ever have these mild pleasures in them. That would be fine, but ‘pretty much always’ isn’t the same as ‘always.’ To the extent that I’m a normal person, I was a normal on the summer day when I took a train to Nice from Marseille, I was normal when I walked up the hill to the Musée Matisse, I was normal right up to the moment when I stepped into the first gallery. Then I wasn’t normal any more, I was overwhelmed. In hindsight I can try to explain it, I can call it a mixture of gratitude and love. I was grateful to Matisse for having made such paintings, and grateful to be standing there with them, grateful for everything that had made that possible. I can use these descriptive terms now; at the time it was all feeling. Not a full-blown case of Stendhal syndrome, but maybe a slight one. It lasted, I don’t know, two minutes?

*

When I was in the Baltimore Museum of Art looking at Anthony van Dyck’s Rinaldo and Armida and the Antioch mosaics and the rest of what I wrote about last month, in the back of my mind I knew there was another part of the museum that was going to matter more. Around the same time that Jacob Epstein and Mary Frick Jacobs were buying the paintings that are the foundation of the museum’s collection of old European art, two other Baltimoreans, Claribel and Etta Cone, took an interest in modern art.3 Cone is an anglicization of Kahn. Claribel, the fifth of the thirteen children of German-Jewish immigrants Herman and Helen Cone, was born in Tennessee in 1864, where Herman had started a grocery business. Etta, the eighth child, was born six years later, after the Cones moved to Baltimore, which in the years following the Civil War had displaced Richmond and Norfolk as a conduit for southern commerce

Herman Cone was a successful wholesaler, but it was his sons Moses and Caesar who made a fortune. Traveling in the South for their father, they discovered that hard-strapped mill stores were unable to pay cash for groceries, and offered the brothers cloth instead. Sensing an opening, Moses and Caesar observed that with its good railway connections, Greensboro, North Carolina would be an ideal place to manufacture denim. In 1890 Herman Cone sold his wholesale business and turned over the proceeds to his sons, who used the money to found what eventually came to be known as the Cone Mills Corporation.

Etta became a pianist and took on the role of managing her parents’ household; the more ambitious Claribel went to the Women’s Medical College of Baltimore. After doing postgraduate work at Johns Hopkins and the University of Pennsylvania, she returned to the Women’s Medical College as a professor of pathology. Claribel never practiced medicine. She had seen one patient in Philadelphia, and that was enough; she preferred the laboratory. She continued to do research at the Johns Hopkins pathology lab, and it was there, in the late 1890s, that she grew close to the worst student then at Johns Hopkins Medical School, Gertrude Stein.

Stein was twenty-four when she entered medical school in 1897. By the time she was thirty she and her brother Leo had established their now-legendary salon in Paris, on the rue de Fleurus near the Luxembourg Gardens. Meanwhile, Herman and Helen Cone had both died, and Claribel and Etta had begun taking annual trips to Europe.

In Baltimore, the company of the relatively free thinking Cone sisters had been a blessing. (Leo Stein: “Baltimore Jewish society… would in a short time stunt anything from a sensitive plant to a sequoia.”) In Europe, by contrast, it was the Steins who were in the process of becoming established. The Cones, however, still had something to offer, something that then (as now, as ever) was in shorter supply in Europe than in the United States—money.

Not that Gertrude and Leo were poor. Shortly after they settled on the Left Bank their older brother Michael sold a streetcar business in San Francisco and, with his wife Sarah, set up a second Parisian Stein household near the first one. But there was more Cone money than Stein money, and this must have been clear to all. One shouldn’t be entirely cynical; for a while the Steins and the Cones were close. They went to Italy together more than once, and the Cones were the subject of Stein’s 1911 prose poem, Two Women.4

Etta began to buy the work of artists whose studios Gertrude took her to; the going rate for a Picasso drawing in 1906 was ten francs, or two dollars. She also bought art from the Steins themselves, and even lent them money, the sort of thing that breeds resentment. The Steins came to see the Cones as pushovers. Claribel Cone, meanwhile, despised Alice B. Toklas, who moved in with Gertrude in 1910. Years later, in 1934, when Stein visited Baltimore to give a lecture on Cézanne, Etta offered to host a dinner in her honor (Claribel had died in 1929). Gertrude snubbed her. “I am seeing no one but a few very dear friends.”

*

So much for mean girl Gertrude Stein. Whatever went wrong in the long run, she was the one who got the Cones started on modern art, though their collecting in earnest began only later. The Women’s Medical College shut down in 1910; by then Claribel seems to have lost interest in medicine, anyway. She spent World War I in a Munich hotel, grateful to be free for once of the burden of sharing Europe with other American tourists. Etta was back in Baltimore, having turned down a marriage proposal from the half-lapsed Mormon sculptor Mahonri Young, Brighman Young’s grandson. For years she mourned for her brother Moses, who had died in his early fifties in 1908.

The two sisters finally returned to Paris together in 1922. By then they had a better sense of what they liked, and more money to spend than before the war. They never, however, came close to matching the quarter of a million dollars Jacob Epstein paid for Rinaldo and Armida. The most expensive Cone painting, Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen From the Bibemus Quarry, cost Claribel 410,000 francs ($18,900) in 1925. One wonders what Epstein thought of the Cézanne, and what the Cones thought of Epstein’s van Dyck. In fact Epstein was a friend and frequent guest of the sisters; on one visit he bumped into an ancient Egyptian cat sculpture that was one of Claribel’s favorite possessions, knocking it over and breaking a piece off.

Claribel’s Cézanne—the Cone sisters were partners in travel, but not in art collecting or life. They had their own bank accounts, and they lived separately, each surrounded by her own paintings, on the eighth floor of the Marlborough Apartments, a beaux-arts pile on Eutaw Place in Baltimore.5 Their younger brother Fred, one of the first Baltimoreans to own a car, occupied a smaller flat between the two sisters. On the few occasions that he bought a painting, either Claribel or Etta ridiculed his taste.

Claribel’s Cézanne—the older sister, especially when the two were getting started, was the more confident spender, and the more likely to buy works by artists who were not Matisse—such as a van Gogh in 1927 and a Courbet in 1929. Archival photos of Etta’s apartment, 8D, show what might be called an intensely Matisse-centric approach to collecting. Which is not to say that Claribel’s 8B wasn’t also full of Matisses. It was, but to a slightly lesser degree. Etta’s taste grew more eclectic after her sister’s death. In 1930 she bought her most expensive work, a Manet pastel, for $17,500. Later in the decade she added a Corot, a Braque and a Gauguin.

Claribel’s Cézanne—but after 1929 it was Etta’s Cézanne. Claribel left everything to her sister, with the understanding that she in turn would leave it all to the Baltimore Museum of Art “in the event the spirit of appreciation of modern art in Baltimore should improve.” The Metropolitan Museum was suggested as an alternate choice, if Baltimore failed to civilize, but the decision was left to Etta.

So for a while it seemed like an open question, and museum directors began to visit. Bill Barr of MoMA, who felt the Cone paintings were “far too good for Baltimore,” was particularly assiduous. But Adelyn Breeskin, appointed director of the Baltimore Museum in 1942, knew that securing the collection was her “main job.” She had Fred Cone appointed to the museum’s board, and in her frequent visits to Etta missed no opportunity to flatter.

Breeskin won the day. When Etta died in 1949 the Cone Collection, along with four hundred thousand dollars for the construction of a wing to hold it, went to the Baltimore Museum.6 But it’s amusing to imagine an alternate history, one with a slightly different will that allowed another Cone to challenge the legacy on the grounds that the spirit of appreciation of modern art in Baltimore had not improved. As a TV series, this might make a decent prequel to The Wire.

*

I was as alone in the Cone galleries as I was with the van Dyck, but it didn’t feel that way. In the room with Rinaldo and Armida I was an aloof observer musing on the relationship Americans have to Europe these days, and the empty gallery was an indication of the changes I thought I perceived. Looking at the Matisses, I wasn’t aloof, I was a lover of Matisse, I myself was filled with the spirit of appreciation of modern art. Not that these paintings knocked me over the way the ones in Nice did three summers ago, but that’s too much to ask for, I probably only get that once. It was enough to stand there, basking in the colors like a lizard on a rock on a sunny day. It was enough to sit on the bench in Gallery 8, the gallery with eighteen paintings, three to six visible at once, depending on which way you face.

I realize I haven’t said anything about Matisse yet. I’ve written about my summer in France; I’ve dwelled on the Cones and the Steins; I’ve even imagined a farcical court case, a trial of the century hanging on the aesthetic preferences of Baltimoreans. I’ve written all this instead of talking about the paintings I like so much, probably because I don’t know what to say about them. Etta Cone was partial to the early Nice period, 1917 to 1930. I am too. It turns out these works, far removed from both early Fauvism and late cut-outs, have been seen as “part of a lazy and conservative interim, not to say a reactionary one.” Well, if the shoe fits. Here are five from these years. (I think the first, The Pewter Jug, might be close enough to Cézanne that it wouldn’t displease the orthodox.)

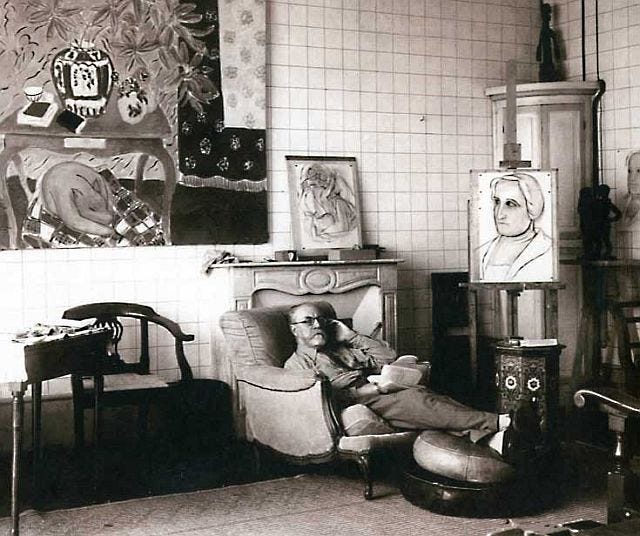

And two more from slightly later, when Matisse’s style was getting flatter and thus less politically suspect. No one will call you reactionary for liking these. I’m not sure if Interior with Dog is my favorite of the Baltimore Matisses, but it’s the most impressive one, a large painting, over twenty-five square feet. I probably spent more time looking at it than any other. In the black and white photograph, the two other works are charcoal portraits of Etta Cone.

Finally, the Purple Robe and Anemones, from 1937. Note the pewter jug, the same one seen in the 1917 painting above. Later on, when he was in his eighties, Matisse said, “I have worked all my life before the same objects. The object is an actor: a good actor can have a part in ten different plays; an object can play a different role in ten different pictures.”

*

I pass over most of the rest of the Cone paintings (and the sculptures, which I haven’t mentioned), but a few words, not my own, on Félix Vallotton’s The Lie, which Etta bought for a little over a hundred dollars in the late 1920s. The below is from an essay by Julian Barnes, a regular in the Cone Galleries when he taught at Johns Hopkins for a semester in the nineties.

...I found myself describing the Vallotton to my class. A man and a woman sit in a late-nineteenth-century interior: yellow-and-pink striped wallpaper in the background, blocky furniture in shades of dark red in the foreground. The couple are entwined on a sofa, her rich scarlet curves bedded between the black legs of his trousers. She is whispering in his ear; he has his eyes closed. Clearly, the woman is the liar, a fact confirmed by the smiling complacency of the man's expression and the way his left foot is cocked with the jauntiness of the unaware. All we might wonder is which lie he is being told. The old deceiver, ‘I love you’? Or does the swell of the woman's dress invite that other favourite, ‘Of course the child is yours’?

At my next class, several students reported back. One, the Canadian novelist Kate Sterns, politely told me that my reading was diametrically wrong. For her, it was obvious that the man was the liar, a fact confirmed by the smiling complacency of his expression and the jauntiness of his cocked foot. His whole posture was one of smug mendacity; the woman's that of the pliantly deceived. All we might wonder is which lie she is being told. If not ‘I love you’, then perhaps that other male perennial, ‘Of course I'll marry you.’ Other students had other ideas; one cannily suggested that the title, rather than referring to a specific untruth, might be a broader allusion – to that necessary lie of social convention, which makes honest dealing between the sexes impossible. Vallotton's use of colour might confirm this. On the left are the couple in sharply contrasted hues; on the right, a scarlet armchair blends seamlessly with a scarlet tablecloth. Furnishings can harmonise, we might conclude; humans not.7

*

When it comes to art I’m not acquisitive. I rarely see something in a museum and wish I had it, maybe in part because I grew up on Indian Jones—museums, I learned from him, are where this stuff is supposed to be. Once in a while, though, I’ll see the words private collection, and gasp. This happened in a little corner gallery where on one side lesser works from the Cone collection have been assembled to recreate the look of their apartments. There are also two comfortable sofas, and there are books to look at. It would be hard to imagine a better place to sit. There’s even an electrical outlet on one wall, and no one minds if, having just taken several hundred pictures, you need to charge your phone.

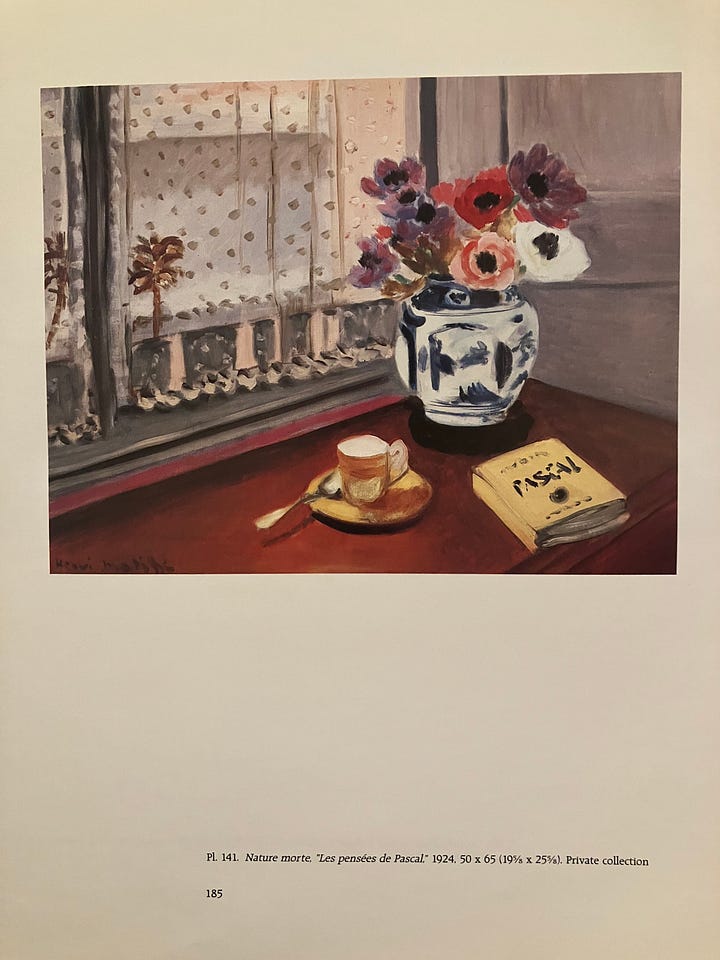

I leafed through a few books. In one, an old Matisse catalogue, I came across a private collection that made me gasp. It was in the caption to a 1924 still life. I’m not sure I wanted it for myself, maybe it was more that it gave me pleasure, slightly illicit due to my Indiana Jones-ism, to contemplate the fact that somewhere out there in the world, in some house or apartment, this painting could be found hanging on a wall.

But no, so much for illicit pleasure, my gasp was out of date. Still Life with the Pensées of Pascal has belonged to the Minneapolis Institute of Art since 2010. It was a gift of Bruce Dayton, an heir to the Target fortune. This is not a paid Substack, but let it be known that I accept travel funding. Send me a note if you have any interest in flying me to Minnesota.

*

Thus far I’ve only written about paintings brought to Baltimore by wealthy Baltimoreans. But Baltimore has its own illustrious art history. This was an important city in the nineteenth century, early on ranking as high as third in population, after New York and Philadelphia. As late as 1920 it was still in the top ten.8 In short, Baltimore mattered, not as much as New York and Boston and Philadelphia, but more than anyplace else. The Peales, America’s first great artistic family, are associated with Philadelphia, where the patriarch Charles Wilson Peale established Peale's Philadelphia Museum in 1784. But they were originally a Maryland family. Rembrandt Peale opened a second branch of the museum in Baltimore in 1814.

I’m fond of the Peales, who, I note in passing, might be due for an exhibition, as it’s been almost thirty years since the last big one, but I will ignore them here, and conclude with another artist, this one a Baltimore native, the African-American painter Joshua Johnson. A few facts about his life have been pieced together from documents.9 The most important of these, from 1782, certifies the manumission of “Mulatto Joshua,” either on his twenty-first birthday or on the completion of his apprenticeship as a blacksmith, depending on which came first. It states that Johnson was the son of George Johnson (‘Johnston’ in the document') and an enslaved woman owned by William Wheeler, Sr. In 1764, the year of Joshua’s birth, Wheeler had sold the infant to his father. Not much more than this is known of Johnson’s parents. His father worked for Wheeler, who was a farmer just outside Baltimore; it has been suggested that his mother could have died in childbirth.

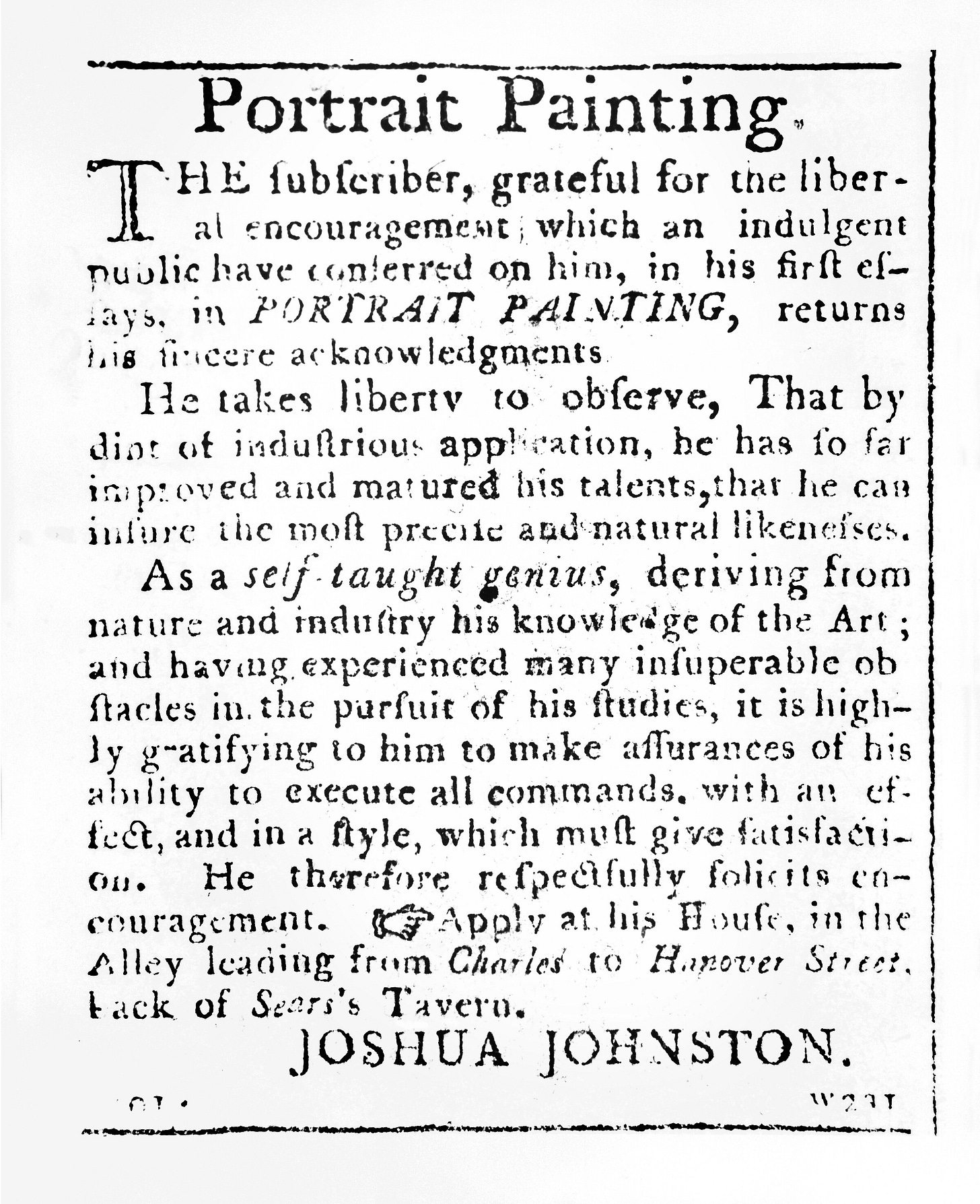

Johnson’s paintings are undated and, with one exception, unsigned (attributions and dates rest on style and, in some cases, family records or lore). It is unclear how and when he transitioned from blacksmith’s apprentice to professional artist. An old hypothesis, that he was a protégé of someone in the Peale family, is attractive, but no one has ever found any evidence for it. However his career began, by 1796 it was underway. That was the first year the Baltimore City Directory was published; Johnson is listed as a portrait painter, or limner. Two years later, in December 1798 he placed an advertisement in the Baltimore Intelligencer, describing himself as “a self-taught genius.”

It’s a bold claim. I’m not sure it’s true; Johnson’s portraits, like those of virtually all untrained artists of his era, are stiff and flat. But what they lack in naturalism they more than make up for in charm. I adore them, and even if you don’t, on strictly historical grounds he’s an important figure, one of the first professional African-American artists, and the first to leave a large body of work.10 I wish the Baltimore Museum of Art would take him more seriously. If a museum owns multiple works by a major artist, the norm is to keep them together. This is how Johnson is treated at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, where four of his paintings hang in Gallery 63.

How strange that he is not granted the same status in his native Baltimore. I found three Johnson paintings in three different rooms, and a fourth on a postcard in the museum shop. My favorite of the three I saw, a portrait of an unknown girl called In the Garden (likely not an original title), is one of fifty-odd paintings in a spacious, salon-style gallery devoted to the work of Maryland artists. My above argument notwithstanding, I grant that it’s a splendid room, and I grant that In the Garden is hung low enough that you get a good look at it, at the girl and at the moth hovering at her side. The label proposes the moth could be a death’s-head hawkmoth; if so, that might mean the portrait is posthumous. You probably know this creature from The Silence of the Lambs. It’s on the poster. There’s also one in Edgar Allen Poe’s 1850 short story, “The Sphinx.” According to Poe, the moth “occasioned much terror among the vulgar, at times, by the melancholy kind of cry which it utters, and the insignia of death which it wears upon its corslet.”11

A second Johnson painting is in a small room in which works are divided into the categories of ‘free person,’ ‘indentured person’ and ‘enslaved person.’ Johnson’s Gentleman of the Shure Family is displayed as an example of an image of a ‘free person.’ According to the wall label, Johnson’s career illustrates “the complexity of race relations in pre-Emancipation Maryland”—true, and all the more reason to give him his own room.12

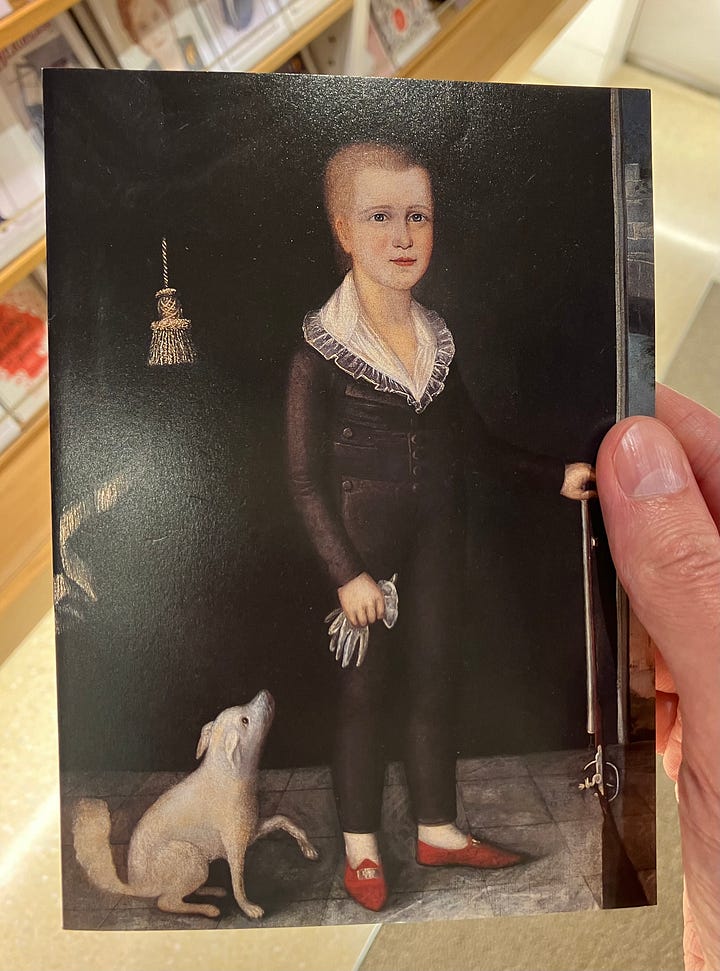

The third painting, Susana Livina Harlen House, hangs elsewhere in the American galleries. Or was hanging in June—the museum website now has Susana Livina categorized as not on view. The fourth work, Charles Herman Stricker Wilmans, was not up when I visited, I only saw it on the postcard, but now it seems to be on display. The young Charles is smartly dressed and wears bright red shoes. He has a pair of gloves in one hand; the other hand rests on the muzzle of a toy musket. A white dog looks up at him eagerly. The setting is a patio (not fully visible in the postcard, which is a detail). A curtain of green velvet half pulled up provides a backdrop, in the manner of old royal portraits. There is a similar Johnson painting (child, dog, patio, curtain) at the de Young Museum in San Francisco in which a girl, Letitia Grace McCurdy, holds out a biscuit above the dog. Can one sense, looking at these works, new forms of art struggling to be born? Art befitting a confident and prosperous young nation; or else art expressing the experience of those it enslaved? I’m not sure. But take him as he is.

Not all Joshua Johnsons are in museums. In 2019 a pair of them sold at Sotheby’s for $675,000, far over the estimate of $60/80,000. I said above that I’m not acquisitive about art, but looking at these portraits I start to wonder if I might not have something of the spirit of Claribel and Etta Cone in me, after all. Latent, of course, my present means preventing it from flourishing as it might.

I am defining ‘long’ as ‘more than a month.’

If you’re wondering why someone might want to go to Arles twice, read this piece by Lydia Davis.

For this section I drew especially from two books, The Cone Sisters of Baltimore: Collecting at Full Tilt, by Ellen B. Hirschlan and Nancy Hirschland Ramage (2008) and Sister Brother: Gertrude and Leo Stein by Brenda Wineapple (1996).

“There are often two of them, both women. There were two of them, two women. There were two of them, both women. There were two of them. They were both women. There were two women and they were sisters. They both went on living. They were often together then when they were living. They were very often not together when they were living. One was the elder and one was the younger. They always knew this thing, they always knew that one was the elder and one was the younger. They were both living and they both went on living. They were together and they were then both living. They were then both going on living. They were not together and they were both living and they both went on living then. They sometimes were together, they sometimes were not together. One was older and one was younger.”

Claribel, who was what would today be called a hoarder, kept another apartment on a lower floor for sleeping.

The $400,000 wasn’t enough. Etta, in spite of having devoted decades to her art collection, was significantly more generous to a projected hospital in memory of her beloved brother. Greensboro’s 310-bed Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital opened in 1953. To complete the Cone Wing the museum had to persuade the city of Baltimore to provide another $175,000.

From “Vallotton: the Forgotten Nabi” in Julian Barnes’s Keeping an Eye Open (2015). I recommend this book, and Barnes’s art writing in general.

Wikipedia has Baltimore in the top ten until 1980, but that’s misleading, as the populations are based on city limits. More useful is a series of historical rankings by metropolitan area, compiled by a mountaineer who goes by ‘Peakbagger.’ Today Baltimore is the twentieth largest metro area in the US.

These were published in “The Mysterious Portraitist Joshua Johnson” by Jennifer Bryan and Robert Torchia, Archives of American Art Journal, Vol. 36, No. 2 (1996), pp. 2–7. Link to PDF.

The first may have been the Boston painter Prince Demah.

I don’t know about a “melancholy cry” but it’s true that the moth makes noise. There are clips, but I rather regret watching one, so I won’t link.

If you want to know more about Johnson watch this lecture on his life, his art and his Baltimore. It was given in 2021 by Daniel Fulco of the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts in Hagerstown, Maryland, for the exhibition, Joshua Johnson: Portraitist of Early American Baltimore. Sad to say, the accompanying catalogue seems to have sold out.

Yeah, I was there in the winter and around Christmas there was a huge storm (the only one I can remember) and we were driving along the Promenade des Anglais and it looked pretty much exactly like that Matisse painting.

Really impressive piece. I enjoyed reading about the Cone sisters and your reflections on the south of France. I spent a year as a student in Nice and also visited the Matisse museum as well as the Chagall museum, although this was 10 years ago and my memory isn't great. I've been meaning to go back...