I considered writing four posts on the MFA rather than two. The second would have been on the short side, a discussion of a few works on long-term loan from private collections; this would have been followed by a third post, covering more of what I saw in Boston in March, and then a fourth one also seemed in order, since I know of several interesting paintings that were not on view when I was there.

In the end, though, I decided that rather than try your patience by writing about the same museum again and again and again, it would be better to try your patience with a one long post incorporating all of the above. So here it is. Let its length make up for the fact that I skipped February.

(You can read my first post on the MFA here.)

Part 2: Long-term loans

It was only after years of regular visits to the Met that I began to notice how many paintings there are on long-term loan from private collections. But it makes sense. Suppose you spent £44,882,500 on a very grand painting by Peter Paul Rubens—as Facebook co-founder Sean Parker did in 2016—where would you put it? Would you feel comfortable having it in your house, or hanging it in a conference room in your philanthropic foundation? What if there was a fire? And then one never knows what a drunken party guest, or else a disgruntled employee, might be capable of. Of course it would be indecent to keep a work like that in storage, treating it like a stack of bullion bars, but also—it has to go somewhere. Isn’t a gallery in a major museum the best of all possible somewheres? If an owner values discretion the label can only say private collection and the object can be kept off the museum’s website, as was the case for the bronze tapir from China’s Warring States period that I included in last month’s post about the MFA. For the less bashful, the label and website entry might read, “Courtesy of the Parker Foundation.”

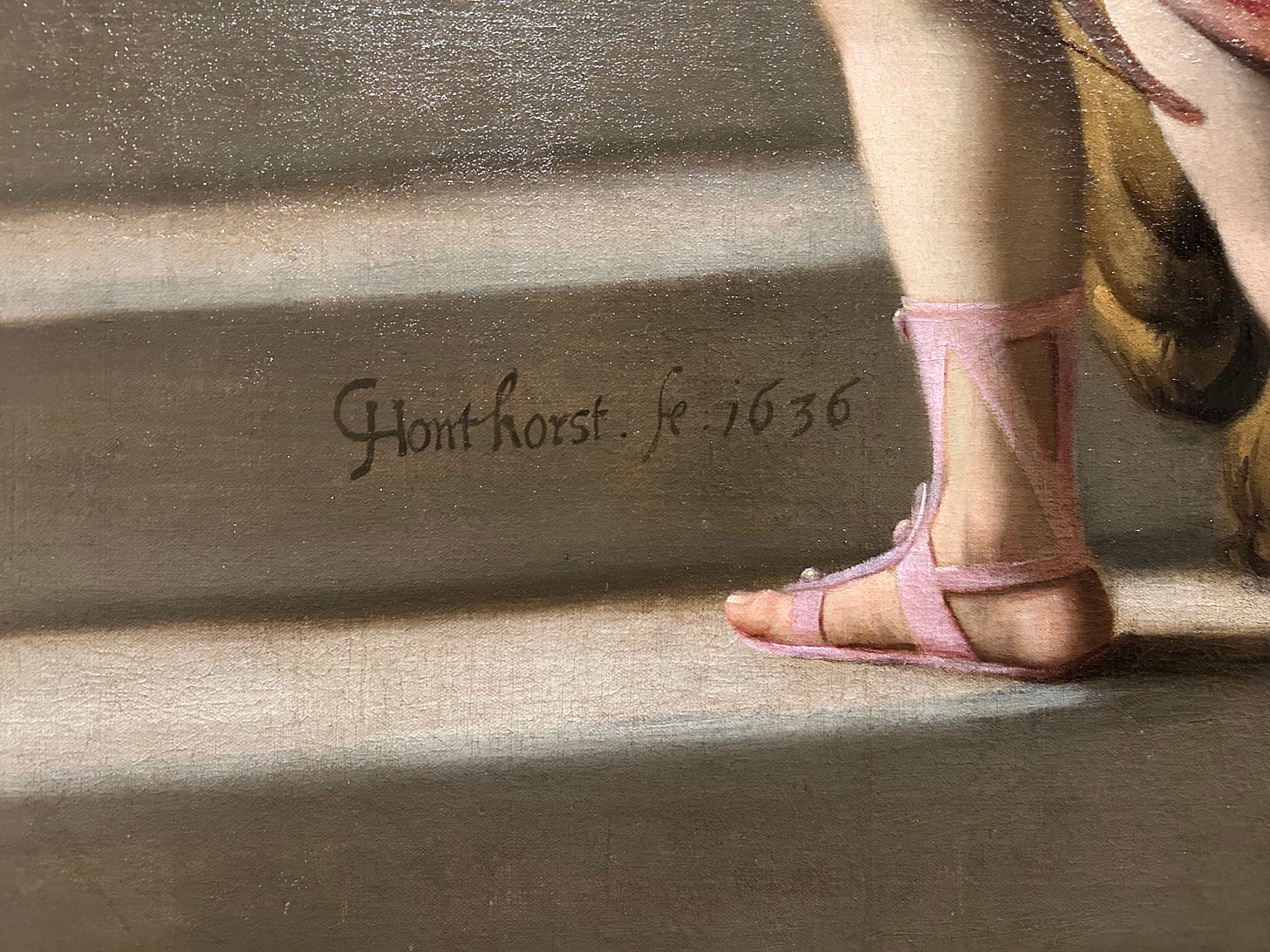

I say all this to introduce a privately-owned painting that may not be the best or the most famous one on view at the MFA, but that is, I think, the most magnificent, and maybe also the most unexpected, namely, Gerrit van Honthorst’s Triumph of the Winter Queen. It’s been at the museum since 2011, first for two years in the conservation studio, where its treatment was documented in a series of well-illustrated blog posts—in the inaugural one the painting enters the museum rolled up in a super-sized version of the kind of tube a movie poster comes in—and since 2013 in its own gallery that’s just right for a single painting measuring ten by fifteen feet. How long will it stay? And whose is it? All I can say that as of 1998, when the Honthorst catalogue raisonné was published, the work belonged to Prince Ernst August von Hannover, and that this prince, in a Sotheby’s sale in 2005, sold a great deal of art, though not, it seems, the painting in question.

Honthorst was one of the ‘Utrecht Caravaggisti,’ a group of three painters from Utrecht who lived and worked in Rome in the 1610s, where they learned to paint in the manner of Caravaggio. As the other two, Dirck van Baburen and Hendrick ter Brugghen, died fairly young, only Honthorst lived long enough to abandon tenebrism when it went out of fashion. His fame rests on his early work, so he is still known by the old nickname, Gherardo delle Notti, given to him sometime after his death for his many candlelit scenes, but there is another Honthorst, an ambitious, mature painter with a classical style that attracted royal patrons.

Not that royal patrons were in plentiful supply in the Dutch Republic, Europe’s parvenu state, but there was Elizabeth Stuart, the “Winter Queen,” so-called for her brief tenure as Queen of Bohemia. The daughter of one English king (James I) and the sister of another (Charles I), Elizabeth was sixteen years old when in 1613 she married Palatine Elector Frederick V and settled with him in Heidelberg, where she devoted herself to two pursuits she excelled at, hunting and child-bearing. In a tranquil era this might have been the story of her life, but meanwhile in Bohemia Protestant nobles were rebelling against their Austrian overlords. In 1618 they tossed two Catholic regents and a secretary out of a third floor window of Prague Castle, and in the following year they refused to accept Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II as their king, offering the Bohemian crown to Frederick instead. With Elizabeth’s encouragement Frederick overcame his sensible reluctance about this 1619 project, and the pair, now royal rather than merely electoral, left Heidelberg for Prague.

Ferdinand, of course, struck back. On November 8, 1620, a year after Frederick’s coronation, the poorly equipped Bohemian army was defeated at Bílá hora, the White Mountain; the imperial army that occupied Prague the next day stayed there right up to 1918, when the Kingdom of Bohemia was dissolved by Woodrow Wilson and Tomáš Masaryk.1 Meanwhile the Palatinate had fallen into Spanish hands, so there was no going back to Heidelberg. Frederick and Elizabeth accepted an invitation from the Prince of Orange to settle in The Hague, where they lived until Frederick’s death in 1632. Elizabeth remained for another three decades, only returning to her native England in 1661. She died in the following year, aged sixty-five, survived by six of her thirteen children.

She worked tirelessly in her exile, first to press her husband’s claims on Bohemia and the Palatinate, and after his death doing the same for her son Charles Louis. The caution others felt about her causes exasperated her, as she wrote in a fit of fury to the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1636 after it became clear England would not take up arms on behalf of her son’s claim:

I remember never to have read in the Chronicles of my ancestours, that anie king of England gott anie good by treaties but most commonlie lost by them, and on the contrarie by warrs made always good peaces2

It was in this state of indignation that Elisabeth commissioned the Triumph of the Winter Queen. Would she have preferred it to be done by Rubens or van Dyck? Presumably, and one imagines that Honthorst, for his part, would rather have continued to work for her brother (he had spent much of 1628 in London, painting for Charles, and had returned to Utrecht that December with 3,000 guilders, a silver service for twelve, and an annual pension of one hundred pounds). But I think they were lucky to have each other.

In the painting, Elizabeth, clad in an ermine cape and holding the scepter of Bohemia, sits in a chariot drawn by lions, one each for England, the Palatinate and the Dutch Republic. Crushed under the chariot’s wheels are Neptune, Medusa and Death. The deceased of the family look down from the gates of heaven at upper left; this group includes Elizabeth’s first-born son, Frederick Henry, whose 1629 drowning in a boat accident explains why Neptune had to go under the chariot. Elizabeth is accompanied in her progress by her ten living children, six sons and four daughters. The two youngest get special treatment. Gustavus Adolphus, in the guise of Cupid, directs the lions up a set of steps (one signed by Honthorst) towards heaven. Little Sophia floats above, poised to place a laurel wreath on her mother’s head. Charles Louis, flanked by two other brothers, stands behind the chariot wearing the hat of the Palatine Elector. The papers held by Elizabeth’s second-youngest daughter, Henriette, may be a reference to a manifesto that Elizabeth was on the verge of publishing.

And what to make of all this? I am not always so fond of magnificent paintings, as I am of this one, and I wonder if half my affection here comes from the incongruities, for example the fact that the work is in a private collection. What an odd object for someone to possess, if these aren’t your ancestors, and what an unexpected place for it to end up. There is a link: Boston itself, give or take a few years, is the same age as the painting. John Winthrop was a contemporary of Elizabeth and Honthorst. But wasn’t Boston founded in a spirit of Goodbye to All That? If the Triumph of the Winter Queen must reside in North America, wouldn’t it have made more sense to deposit it in a museum in Virginia, where the colonists of the seventeenth century held the Elizabeth Stuarts of the world in higher regard, and where in fact there is a six-mile tidal estuary named in her honor?

*

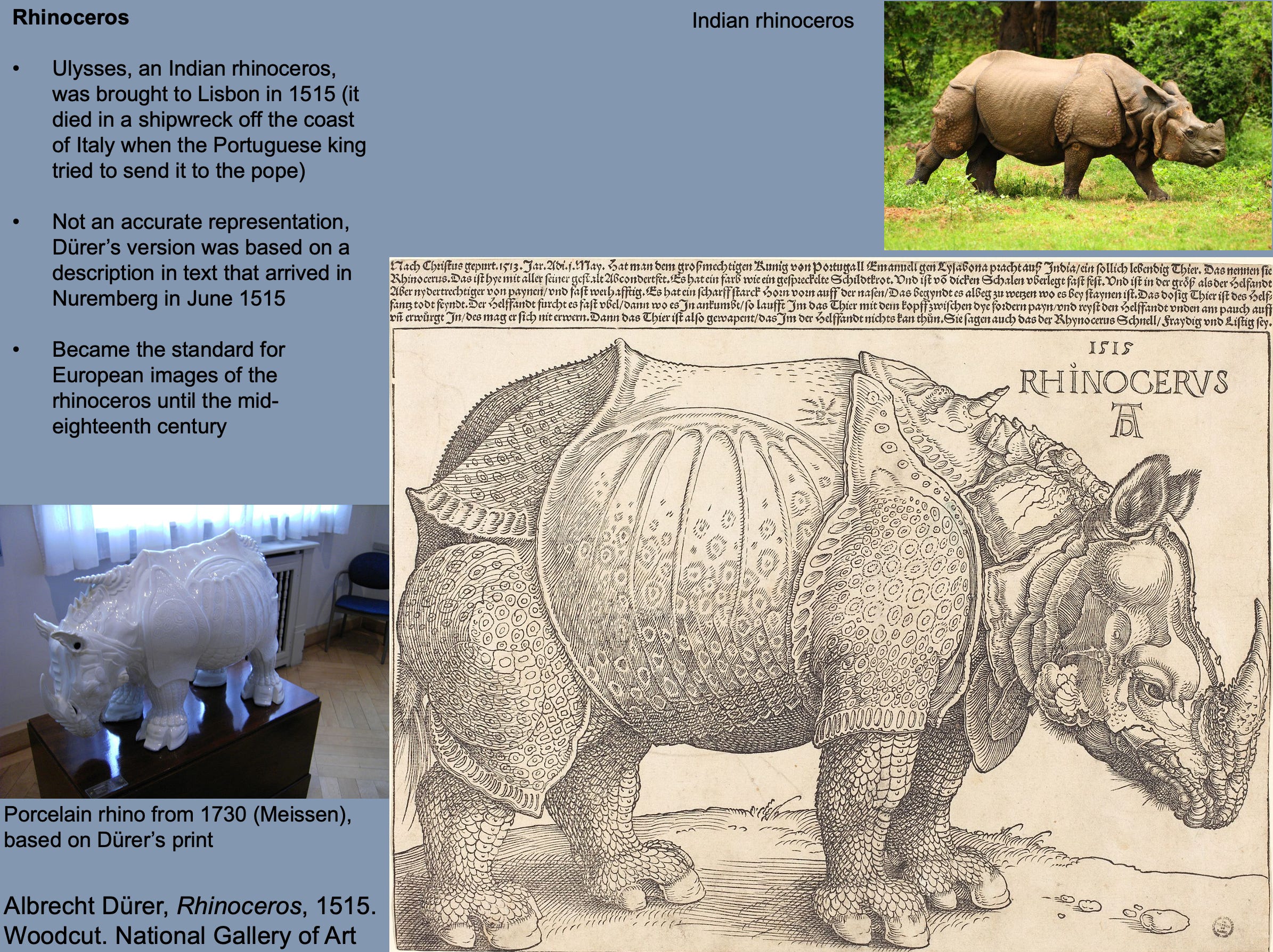

One of the clichés of an art history survey course is that Albrecht Dürer’s misconceptions about rhinoceros anatomy—the plate armor skin, the scales, the additional, dorsal horn—shaped European representations of the rhinoceros for centuries. As seen on a slide I showed to my students this semester, with Dürer’s woodcut and a Meissen rhino from 1730.3

Europeans of course having had ample opportunity in the interval to correct Dürer’s mistakes, the comparison is meant to demonstrate the durability of a viral image, however misleading—or, to quote from Umberto Eco’s Theory of Semiotics:

…this image of the rhinoceros remained constant for at least two centuries and reappeared in the books of explorers and zoologists… they knew that only these conventionalized graphic signs could denote «rhinoceros» to the person interpreting the iconic sign.

A compelling statement, but is it true? Two rhinos at the MFA made me wonder. They are among the many animals in pietra dura (hardstone mosaic) that adorn a pair of cabinets, dating to the 1670s, that constitute another long-term loan from a private collection. At the center of each cabinet, set in an elaborate, columned encasement of tortoiseshell and red coral, is a panel of Orpheus charming animals with a viol; this in turn is flanked on each side by eight more panels of individual animals, the full spectrum from domestic (cows, goats) to exotic (camels, elephants, rhinos) to mythical (unicorns, centaurs, dragons). The cabinets were made in Palermo using coral from Trapani; the animal mosaics were imported from Florence, the center of pietra dura production since the founding of the Galleria dei Lavori manufactory in 1588.

Each cabinet has a rhino that is not based on Dürer, and it turns out there are more where these came from, Orpheus cabinets having been all the rage in the seventeenth century. The Detroit Institute of Arts also has one with a rhino, there’s another similar cabinet on the art market (Thomas Coulborn & Sons, London, price on request), and a third, at the Met, features scenes from Aesop’s Fables rather than individual animals (no rhino there). Plenty more have turned up at Christie’s and Sotheby’s over the years, only to disappear back into private collections.4

So what was the model for these Florentine mosaic rhinos, if not Dürer? The answer may be that they are based on an engraving of Abada, a female Indian rhino who was the second one to come to Europe in modern times. Abada arrived in Lisbon in 1577, probably as a gift of the viceroy of Goa to King Sebastian I of Portugal. Sebastian I died soon afterwards; his successor, Henry I, only reigned for two years. On his death the throne of Portugal was taken over by Philip II of Spain, who had Abada sent to his menagerie in Madrid, together with an unnamed Indian elephant. The two animals were later moved to the Escorial, where Abada died sometime in the late 1580s.

Thanks to a database of nearly seven thousand images maintained by the Rhino Resource Center, I feel confident stating that Abada was portrayed in print only twice, first in a woodcut of 1585 that heads a chapter in a manual for artists by the Madrid goldsmith and printmaker Juan de Arphe y Villafañe, and then in 1586 in an engraving by the Amsterdam printmaker Philip Galle, presumably after a now-lost drawing of Abada that was sent to Galle from Spain. Both artists dispense with the dorsal horn (though Arphe-Villafañe’s rhino otherwise resembles Dürer’s). It seems doubtful that the woodcut circulated far beyond Madrid, but Amsterdam at the time was at the dawn of its long reign as a center of art and trade. Prints made there were likely to be seen throughout Europe. Copies after Galle’s rhinoceros by two more printmakers, Lazarus Roeting and Galle’s nephew Adriaen Collaert, were incorporated into natural history texts. Collaert’s version, in turn, was copied by still other artists. As the Rhino Resource Center puts it—pace the art historians and pace the semioticians—“Dürer had no monopoly.”

Part 3: European and American paintings

Of course sponsorship makes sense for institutions, but it’s a pity to lose an old, plain name. I have confirmed, from the title of a drawing made by Barbara Westman in 1975, that the William I. Koch Gallery, where the MFA displays about three dozen paintings, mostly from the seventeenth century, was formerly the Great Hall.5 The walls used to be bare marble, but I think the choice to hang it with red velvet (or is it damask?) in the summer of 2012 was a good one. In a time-lapse video of the renovation the room seems more spacious by the end. When it reopened with its new look, the critic Judith Dobrzynski reproached the museum for installing a pyramid of Hanoverian silver, “a huge, garish display” that in her view demeaned the adjacent paintings.

As much as anyone can admire silver, it doesn’t really rise to the artistic and aesthetic value of masterpiece paintings, does it?

If I had given the pyramid two glances I might have come to a similar conclusion, but since I didn’t, I guess it’s possible to ignore it? So sure: it would probably be better to put the silver somewhere else, and hang four or five more paintings, but there’s plenty to see here as it is.

There is no work in the Koch Gallery that I would call canonical, but there are at least two that could be, and both of them would make the canon more interesting if they were. Juan de Pareja is a great and important painting, and the Met’s decision to spend a record-breaking sum on it in 1970 looks better all the time, but as paintings by Velázquez go, is it all that interesting? I don’t think it’s even close to as interesting as the MFA’s Don Baltasar Carlos and an Attendant (or, as it was known until recently, Don Baltasar Carlos with a Dwarf6).

Born in 1629, Baltasar Carlos was the only son of the union of King Philip IV of Spain and his queen, Elisabeth of France. When Baltasar Carlos died of smallpox in 1646, the Spanish crown was left without an heir. Elisabeth having died in 1644, it became necessary for Philip to remarry, which he did, in 1649. His second wife, Mariana, was the Austrian princess originally promised to his son

All of this was in the future in 1631, when Velázquez, just returned to Madrid from a long embassy in Rome, painted Baltasar Carlos with one of the resident dwarves of the Spanish court. The identity of the dwarf has never been determined, nor has the gender, though one plausible analysis, based on costume, suggests female.

The identity of a dwarf in a Velázquez painting—only a specialist on the Spanish court could take an interest in such a question. There’s another mystery here, though. It is striking how much more alive the figure of the dwarf is, than that of the prince. Not only do the two not interact, they barely seem to occupy the same physical space. In a catalogue entry for a 1989 exhibition at the Met, the Spanish art historian Julián Gállego made a tantalizing proposition. Having observed a horizontal line dividing the carpet in the foreground into sections, he suggested this is a panting of a painting—the dwarf is standing before, to quote Gállego, “a replica of a hypothetical 1631 portrait by Velázquez.”

Velázquez experimented with conceits of this nature early in his career, in two of the kitchen scenes (bodegones) he made before he left Seville for Madrid, Christ in the House of Martha and Mary and The Supper at Emmaus. In both paintings there is ambiguity about the biblical scene in the background—is it depicted in a painting on the wall, or is it taking place in the next room? Late in his life he revisited the format. There is a tapestry version of Titian’s Triumph of Bacchus in the The Spinners (Las Hilanderas), and then, of course, there is the most celebrated painting within a painting in the history of Western art—the canvas, seen only from behind, on which, in Las Meninas, Velázquez himself is at work.

But maybe Gállego was just reading too much Foucault? I can’t help noticing that the tasseled pillow on the right, which, if Gállego is on to something, should be part of the painting within the painting, seems to occupy the same space as the dwarf. If it does, there can be no painting within the painting. An alternate theory has Velázquez adding the dwarf in 1634, in which case it could represent Francisco Lezcano, who came to the court that year. And it may rather be that, instead of being embedded as a portrait, Baltasar Carlos is expressing, to quote Gállego again, “that lofty remoteness characteristic of the Habsburg sovereigns.”

But then, why would Velázquez add a dwarf two years later? And is there any denying that the perspective seems to shift at the line dividing the two sections of carpet? How else to account for that? The art historical consideration that the painting, if the theory is true, fits neatly into the career of Velázquez by linking the bodegones of his Seville days to the late masterpieces, is hardly persuasive on its own, but it doesn’t hurt. So in short: I love Gállego’s theory, I want it to be true, and who knows, maybe it is.

*

No living man or woman can remember a time when Velázquez was not considered the greatest of seventeenth century Spanish painters, but if you were to run the artistic stock market back a little further the reputation of Velázquez would start to sink, and that of another artist from Seville, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, would correspondingly rise. As the Scottish artist and writer William Bell Scott put it in his 1872 Murillo and the Spanish School of Painting, Murillo was

…in the estimate of nearly every writer on the Spanish Schools, and of every public and private collector in Europe, the greatest painter Spain has produced. Compared to him there are three who may be preferred by those who are exclusive or peculiar in taste, or who object to the common nature of Murillo: these are Zurbaran, whose sympathies were in the cloister; Ribera, whose power of hand is as great as that of Tintoretto, whose sympathies were cruel; and Velazquez, who was essentially a portrait-painter. But Murillo was wider than either or all of them perhaps, and the beauty of his treatment, and mastery of his technique, has made him, in spite of a commonplace character and coarseness of mind that places him below the greatest of the Italian masters, the representative name in the art of Spain.7

Clumsy prose, but you get the idea. A decade later the New York merchant and connoisseur Charles Boyd Curtis, in a joint catalogue of the paintings of Velázquez and Murillo, noted with skepticism “the fashion now-a-days with a certain class, to exalt Velazquez and decry Murillo.” Defending conventional wisdom, he observed that “the best pictures of Murillo have sold, and will sell, for more than those of any artist except Raphael”—and this he considered conclusive evidence, for “in the long run a man passes for what he is worth… there is no test of merit so safe and decisive as success.”8 And he was convinced the status quo was stable: “Murillo has always possessed, as without doubt he always will possess, the public esteem.” I suppose we are just as sure about Velázquez today.

A few decades later what had for centuries gone down as sweet in just the right way—the street urchins, the Immaculate Conceptions, the Biblical scenes—now seemed cloying. Murillo paintings were everywhere, reproduced on wax plaques, cheap porcelain, gaudy postcards. In Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage, published in 1915, the protagonist’s circle of young painters—or maybe they’re only yappers—disparage Murillo and his city as they compare artists and plot trips to Spain. “[Seville’s] facile charm can offer permanent entertainment only to an intelligence which is superficial… there is nothing but the obvious there; and it is all finger-marked and frayed. Murillo is its painter.”

Today his shares are back up a bit. Murillo is admired for his drawings; he has come to be seen as a cosmopolitan artist attentive to developments in other countries (as one might expect of a painter working in a port city that, though it was in precipitous decline throughout his life, even in its reduced state remained one of the principal cities of Europe); and some of his secular works have turned out to be maybe not so sweet, after all. What I want to propose is that it is possible not all of his religious works are sweet, either.

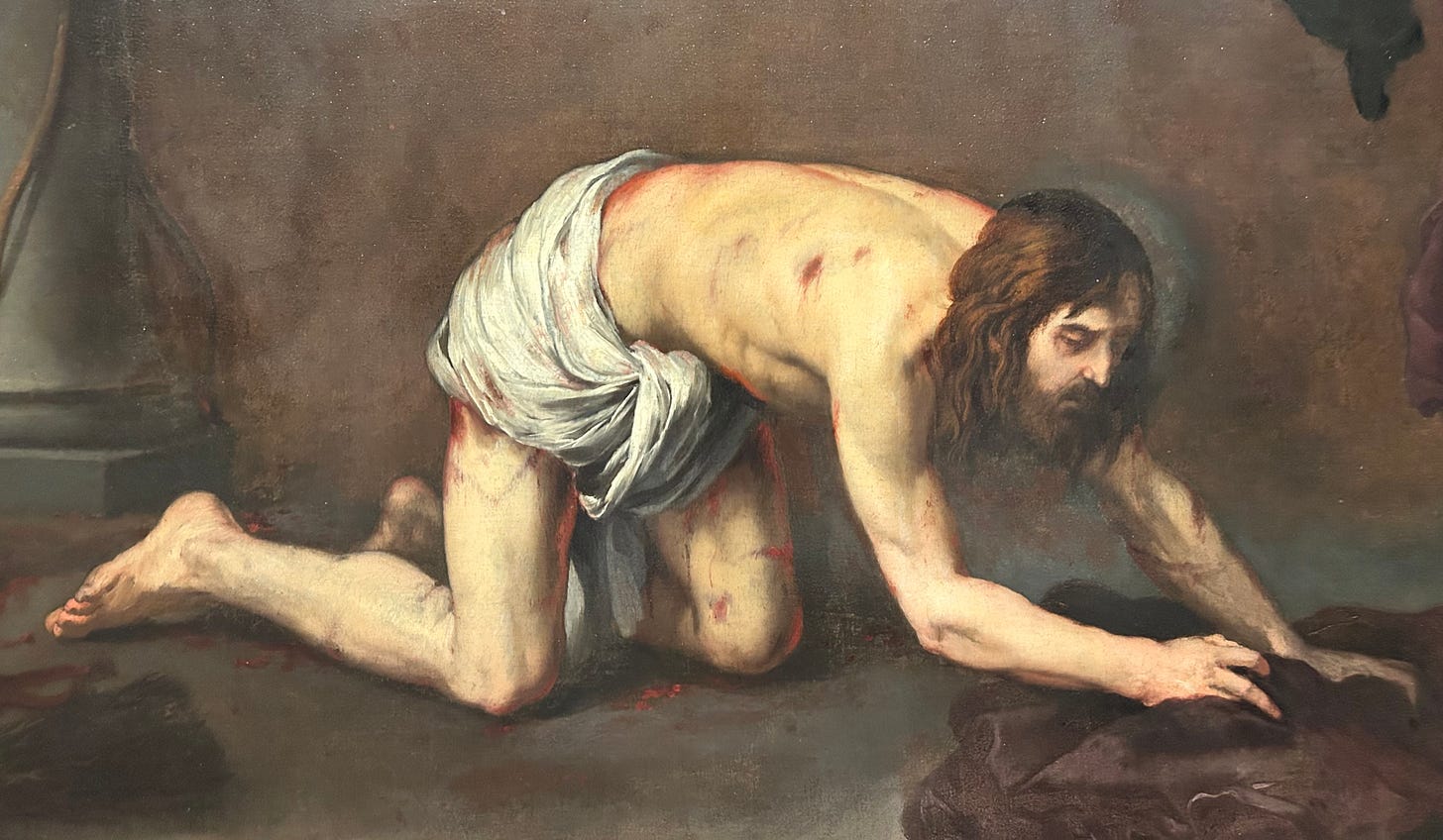

I didn’t go through the MFA’s European galleries in chronological order. When I found myself in front of Murillo’s Christ after the Flagellation, I had just been looking at Symbolist paintings, the big, famous Gauguin, an odd, semi-demonic creature by Odilon Redon, and a mysterious vision of a woman on a Scandinavian midsummer night by Edvard Munch. This is the kind of art the youths in Of Human Bondage probably would have liked had they been a little less provincial, if they had they been up on the latest Continental trends rather than a few decades behind.

Looking at this Christ—more bewildered than bloody, alone, silent, unaware of the angels looking on—I wondered if, by not overdoing it with the blood, by making a painting of confusion and loss rather than one of physical suffering, Murillo had not beaten the Symbolists at their own game.9

*

My first idea for writing about the MFA’s Dutch and Flemish art, a collection enriched in 2017 by two gifts from Boston-area collectors that together amounted to 114 paintings, was to focus on what the MFA has that the Met lacks—the examples I had in mind were two still lifes by Adriaen Coorte (to the Met’s zero), three church interiors by Pieter Jansz. Saenredam (again to the Met’s zero), and a landscape by Jacob van Ruisdael in which sheets of linen have been put in the sun for bleaching (both the MFA and the Met have Ruisdaels but only the MFA has one of the linen bleaching paintings). Unfortunately, both Coortes were off view, as was the Ruisdael and one of the Saenredams.10

I also considered writing about Aelbert Cuyp’s Orpheus Charming the Animals, together with a nineteenth-century American painting, Erastus Salisbury Field’s Garden of Eden. This would have continued the Orpheus theme from the cabinets with rhinos discussed above, and, both paintings being full of birds, also the ornithological theme from my first post about the MFA (the cockatoo painting, the print with sparrows, the bowl with pelicans). But then: while my penchant for writing on Substack about birds in paintings has in fact led to a forthcoming academic article, and while I am fond of both of these works, it is possible to overdo it with animal art.11

Since starting this newsletter I’ve mostly ignored works on paper. This is not because I don’t find them interesting (my dissertation was on prints), but rather because implicit in the name Permanent Collections is, if not a promise, then at least a hope, that if you go to a museum after reading about it here, most of what I wrote about will be on display. Since even small museums have thousands of works on paper, and larger ones have tens or hundreds of thousands, rotation is inevitable; even the standout works in a collection might only be up for a few months in the course of a decade. (Incidentally, it would be an interesting curatorial experiment for the Met to put everything else in storage for a year, and give the entire museum over to its Department of Drawings and Prints.)

So works on paper would seem to be out, but looking over the pictures I took in Boston another way to write about them occurred to me. Sometimes paintings are based on prints, and sometimes there are prints in paintings. A famous example of the latter is Caspar Netscher’s Lacemaker, at the Wallace Collection in London, in which a landscape print, signed and dated by the artist but likely based on a reproduction after Adam Elsheimer, is pinned to a wall beside which a woman is at work on a piece of lace. Or I should say, so as not to mislead, the painting is famous, but its fame is not based on the print on the wall, that’s just why it’s famous to me. I like the way it seems to let the viewer in on a secret: here is how prints were actually used.

I come across another such work at the MFA, the Butcher Shop of the Flemish artist David Teniers the Younger, painted in 1642 during the first half of the career of Teniers, the Antwerp half, before he moved to Brussels in 1650 to be court painter to Archduke Leopold Wilhelm, Governor General of the Spanish Netherlands. Today Teniers is probably best known for genre paintings, which he made throughout his career, but he is also a key figure in the history of reproductions of artworks, thanks to his Theatrum pictorium, an illustrated catalogue of 243 Italian paintings in the Archduke’s collection that was published in 1660. It was the first such catalogue. To help the dozen engravers who worked on the project, Teniers made a reduced version (modello) of each painting. Three and a half centuries later, those of the modelli that survive are dispersed. Most of the Archduke’s paintings, however, remain together—they’ve been in Vienna since the Archduke left Brussels in 1656, and are now at the Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Anyway, the Butcher Shop—no one writing about this painting has paid much attention to the sheet of paper on the right wall, depicting a figure in a hat holding a glass and dated 1642. Understandable, given how much else there is to take in. First, there’s the carcass of an ox, hanging from a beam suspended from the ceiling, dripping blood into a bowl, which—sorry—a dog laps up. The creature’s head and pelt (complete with horns) are nearby on the left, and the tongue is pinned to the adjacent wall. To the right, to use the words of the catalogue prepared for the painting’s sale in Paris in 1880, “une jeune et jolie fille débite les poumons et le foie d'un bœuf gigantesque” (“a young and pretty girl carves up the lungs and liver of a gigantic ox”). Still more: a man (the butcher?) and a woman stand by a fireplace in the background, another man walks out the door, a duck hangs upside down from the ceiling, there is a sieve affixed to the wall by the tongue.

And then what to make of the white cloth that hangs from a rod that holds open the carcass? The rod itself is easily explained. To quote a scholar writing about the one in Rembrandt’s Slaughtered Ox, it “widens the cavity to cool the animal down and allows the butcher to pull out the viscera.”12 But there is no cloth hanging on the rod that pries open Rembrandt’s ox’s, and the cloth in the Teniers painting goes unmentioned in the descriptions I found.

The best of the descriptions, from the catalogue of the MFA’s 1993 “Age of Rubens” exhibition, links the slaughtering of oxen to the virtue of prudence and month of November, November being a sensible time to store up meat. There may also be a connection to the fatted calf in the parable of the Prodigal Son. As for the sheet of paper, the same catalogue entry describes it as “a bust-length drawing of a peasant holding a glass.” I don’t know, though, why it should be thought of as a drawing rather than a print, since prints were likelier decorations for such premises.

In any event, the sheet on the wall may not be as interesting as I hoped. Looking at more paintings by Teniers, I found that he had a habit of putting such sheets on walls (see here, here and here), and he never did it with the kind of specificity apparent in Netscher’s Lacemaker, or for that matter with the specificity of his ox carcass. Rather than investigating the interior decorating preferences of seventeenth century Flemish butchers, as I had hoped, I seem to have written about one more animal painting, after all.

*

My choice of a second print-related work also turned out to be not as print-related as I had thought. It is a portrayal by Rubens of Mulay Ahmad, who in the mid-sixteenth century was the king of Tunis (more properly: caliph of the Hafsid Sultanate). Mulay Ahmad’s father, Mulay Hasan, was driven out of Tunis in 1534 by the Ottoman-sponsored corsair Barbarossa. Hasan, in exile in Spain, appealed to Charles V, who was persuaded not only to launch an invasion to reinstall Hasan, but to command it himself. In May 1535 over two hundred Spanish, Portuguese and Genoese ships carrying thousands of soldiers set off for Tunis from Barcelona.

Tunis was conquered, and Hasan returned to power; meanwhile the Flemish artist Jan Cornelisz. Vermeyen, brought along to document the expedition, made drawings. These have been lost, but about a decade after the victory Charles V asked Vermeyen to design a commemorative tapestry set. The resulting dozen tapestries, woven in Brussels by the Pannemaeker workshop, set a new standard for royal propaganda.

In addition to the tapestries and the lost drawings, Vermeyen made a few prints related to Tunis, including a portrait of Mulay Ahmad and a scene of Mulay Hasan dining with his retinue by candlelight. I had long assumed, hence my decision to write about it here, that Rubens based his painting on the print. No—Rubens’s source was not the print, but a lost painting by Vermeyen. There is evidence for the existence of such a painting (and also one of Mulay Ahmad), but even without any evidence its existence could be guessed at, since the Rubens painting reverses the print—and if Rubens had been working from the print, there would have been no reason to reverse it.

Rubens held on to Mulay Ahmad as a tronie, or stock character, to insert in other works. The figure appears, for example, in an Adoration of the Magi Rubens painted for Mechelen Cathedral around 1617. It’s easy to understand why he liked the painting, Ahmad ready with his sword, eyes askance, Carthaginian ruins in the background—but don’t you prefer the print, so much more sharply defined, and inscribed in Latin and Arabic?13 And wouldn’t it be splendid if there were an impression of it for the MFA to hang next to the painting? Sad to say, it’s such a rare print that there may not be one floating around. I found only two in museums, the one at the Albertina illustrated here and a second in Rotterdam. Still, if another turns up on the market, I defy you to think of a better use of a hundred thousand dollars (a different but comparably scarce Vermeyen print went for £52,500 in 2015) than to buy it and either donate or make an anonymous or not-so-anonymous loan.

*

In June 1774 John Singleton Copley, thirty-five years old, left Massachusetts for good, settling in London the following year after a Continental tour. As he worked well into his seventies, his British career was longer than his American one, but in the long run London has proved indifferent to Copley. There is no painting of his at the National Gallery, not even in storage, and of the Tate Britain’s five Copleys just one is presently on view. Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, the Met displays nine Copleys, the National Gallery of Art eleven and the MFA thirty-three—and I’m not counting the miniatures. Of course we need him for our eighteenth century more than they do for theirs. They have Reynolds, Gainsborough, and the rest.

We have Copley’s colonial-era paintings in our museums, and as there has been a long, steady flow of his later work to North America, we have many of his London paintings, too.14 “No present could have been more acceptable,” wrote Abigail Adams to her son John Quincy in 1797, upon receiving the Copley portrait Adams sat for during his tenure as United States Minister to the Netherlands. And then there is the famous Watson and the Shark, which hung in a London hospital until the National Gallery of Art bought it in 1963.15

My favorite of the Copleys at the MFA is neither a colonial nor a London painting. Soon after arriving in Europe in 1774 Copley met, in Florence, the Charleston merchant and planter Ralph Izard and his wife Alice (née De Lancey, from the family that gave its name to the street in Lower Manhattan). There’s a lecture from 2011, I chanced to hear part of it late at night on C-SPAN radio at some point, in which David McCullough speaks of the fellowship Americans can feel when they meet abroad.

Now when we travel abroad, and we've almost all of us had this experience, and you run into another American or some other Americans, you very often strike up a friendship that's different from otherwise would have happened. There's something about being away from the home and the homeland that when you see someone else, you bond pretty quickly.16

This must have been the story of Copley and the Izards. In January 1775 the three traveled together to Naples, where they visited (and it has been suggested that they were the first Americans to do so) Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Paestum. Then, after they moved on to Rome, Copley painted for the couple a souvenir of their trip, a large canvas in which the Izards are seated at a porphyry table. Behind them is a sculptural group that has been identified as a reduced copy of a sculpture of Orestes and Electra that is now at the Palazzo Massimo, and Ralph holds in one hand a drawing of the group, presumably his own. There’s also a Greek vase, a green marble column, the Colosseum in the distance, and a dozen other references to the Izards’ (and, implicitly, Copley’s) taste and connoisseurship.

Copley had not finished the painting when the Izards left Rome to return to London, where they had been living prior to their trip to the Continent. By the time he brought it there later in the year Lexington and Concord had happened and Ralph Izard’s circumstances had changed. He had been the richest man in Charleston, and the only one to own property in London; now the remittances stopped arriving, and, unable to book a passage back across the Atlantic, he sold his house on Berners Street in London’s West End and moved with his wife and their two daughters, first to a suburb, where a son was born, and then, in 1777, to France, where he hoped for an appointment receiving American rice. The Continental Congress instructed him to go to Florence instead, where it was hoped he would be able to procure a loan from the Grand Duke of Tuscany. This loan seeming an unlikely prospect, he remained in Paris to feud with Benjamin Franklin over the provision for molasses duties in the trade agreement then being negotiated with France.

Izard crossed the Atlantic in 1780, leaving his wife and children in Paris; they finally joined him in Charleston in 1783. By then he had been involved in the war for independence for the better part of a decade; his time sightseeing with Copley must have seemed like a memory from another life. Even after his finances were back in order he may have been too busy to try to get his painting. He represented South Carolina in the Congress of the Confederation, and then in the First United States Congress, as senator. It would be fair to say he was a figure in the early history of the republic. A minor figure, but also the only one to have been depicted as a cultivated man of leisure on a Grand Tour, sitting with his wife in view of the Colosseum.

It probably suited Copley that the Izards never took possession of the painting. He exhibited it at the Royal Academy in 1776, and he likely kept it on view in his studio thereafter as an advertisement of his skill in portraiture. It was still there when Copley died in 1815; a decade later, in 1824, his widow sold it to Ralph Izard’s grandson, Charles Izard Manigault. The painting was at last brought to Charleston, where it remained until 1903, when, four years after the death of Charles’s son, Dr. Gabriel Edward Manigault, the MFA purchased it from his estate for $7,250.17

While looking at Copley’s painting of the Izards in Boston I was reminded of another Grand Tour souvenir I saw a few years ago, at the Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston. And for good reason, it turns out. The Charleston painting, done in Rome in 1831 by Ferdinando Cavalleri, depicts the family of Charles Izard Manigault, the same Charles Izard Manigault who retrieved Copley’s painting of his grandparents from London!

It is tempting, from here, to use the two paintings to open a discussion of the differences between the Grand Tour of the eighteenth century and that of the nineteenth, but no—let that wait for the catalogue of the exhibition that brings these two works together, which I am now determined to make happen (someday). Another possible topic for the catalogue: I would like to find out how Copley and the Izards got along in London between the time of Copley’s arrival there with the painting in the second half of 1775 and the Izards’ departure for France in 1777. Could they have remained as close as they had been in Italy? Or did they quarrel about the war? This I doubt—Copley had married into a Loyalist family, but he was not a strong partisan himself, and as for Izard, he was less a republican than a man a who had property in South Carolina. Could Copley have snubbed the Izards when they ran out of money? If, as seems to have been the case, Ralph Izard never tried to get the painting, not even after he had more or less regained his old prosperity after 1790, might that be interpreted as a sign of bad feelings between the two men?

*

All this about Copley and the Izards is fascinating, and it’s true that the painting was my favorite of the Copleys I saw at the MFA, but how much is that saying? I doubt anyone has ever been hospitalized with a case of John Singleton Copley-induced Stendhal Syndrome. If I were to make a Venn Diagram with circles for artworks I find interesting and artworks I love, the Copley, like much of what I write about on Substack, would be in the first circle but not the second. There are also cases of overlap, artworks I love and want to learn about, or else artworks I grow to love through learning about them, but I wonder if there are any I prefer to love in ignorance. I’m tempted to say that Dana Smith’s New Hampshire Panorama belongs to the last category. I feel no scholarly compulsion here, but then there’s no way to be sure, since all I found out about Smith was this:

Very little is known about Dana Smith, the supposed painter of the National Gallery's painting Southern Resort Town (1971.83.11) and New Hampshire Panorama (also a Garbisch gift, to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). According to the Garbisch records, he was born in New Hampshire in 1805, lived in Franklin where he painted local scenes and died in 1901, but no trace of him has been found in Franklin genealogical sources. The origin of the Smith attributions is unknown.18

Perhaps there never was such an artist? No matter; it is a painting to get lost in.

Part 4: What I missed at the MFA

On December 15, 2021 I went to Boston for the day to see the Poesie, the series of mythological paintings, that Titian made for Philip II of Spain. They had been brought together at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum for “Titian: Women, Myth & Power.” Pretentious, but never mind, to get worked up over exhibition titles is no way to live, better to be glad to have seen the paintings in one place—the room shimmers in my memory, all that lush color on one of the darkest days of the year. After seeing the Titians and having lunch at the Gardner I walked over to the MFA and came across Running before the Storm, a painting from about 1870 by an unknown American artist. The label explained that it was based on a print by John Sartain. I wondered who that was, and what the print was like, but never got around to checking.

This time, in 2025, Running before the Storm was not on view. I was surprised—who could put such a painting in storage? But someone did. Luckily I have my pictures from 2021.

Why isn’t this painting known far and wide? The pair of prancing horses, the man’s hat seized by a gust, the laundry flapping on the line, the bolts of lightning—is this not the real thing? Has any artist ever come closer to the spirit of the fourth movement of Beethoven’s Pastorale?

The original for the painting (and after my failures with Teniers and Rubens to connect the two media, here is a painting that does have a print-original) ran in a book by Herbert W. Morris, Work-Days of God, or, Science and the Bible. This book, published in Philadelphia in 1877, is pretty much what you’d expect from the title. As Morris writes in his preface:

Two great Volumes have been laid before man for his instruction, and from which his ideas and science all have been derived—the material Works, and the inspired Word of God. These being the productions of the same wise and unchangeable Author, the harmony subsisting between them is universal and complete. Both have for their end the manifestation of the invisible Deity. While in the Bible we have a verbal revelation of the wisdom and power and goodness of God, in material Nature we have a pictorial revelation of the same…

Sartain’s print, Thunderstorm, illustrates a chapter on electricity. Morris again:

It is when the volleys of the bursting cloud cleave the firmament, and the thunders of the discharge are pealing their dreadful notes above our heads, that the chemical combinations of the noxious exhalations arising from decaying animal and vegetable substances, are effected, and the elements, fitted for the purposes of animal health and vegetable growth, are formed and brought to the ground in the heavy rains which usually attend these storms. It is by these convulsions that the atmosphere regains its balance, and renews its salubrity. Thus Science unites with Revelation in teaching us, that our Father in heaven is no less loving and kind in launching forth the “winged bolt,” than in sending down the gentle sunbeam.

Fine. But the print is a bit of a letdown. The man’s hat is still on his head. There is no laundry line in the yard. The wind blows, but maybe not with the same intensity as it does in the painting, where every branch seems stretched almost to breaking point.

As for Sartain, he was an English-born printmaker who had a long and successful career in Philadelphia. He was a friend of Edgar Allen Poe (Annabel Lee was first published in the short-lived Sartain’s Union Magazine) and the author of a late memoir, The Reminiscences of a Very Old Man, 1808–1897. Sartain’s Wikipedia entry claims that this work is “of unusual interest.” Maybe it’s even true. Here’s Sartain on the death of Poe:

The accepted statement that Poe died in a drunken debauch is attested by Dr. Moran to be a calumny. He died from a chill caused by exposure during the night under a cold October sky, clad only in the old thin bombazine coat and trousers which had been substituted for his own warm clothing.19

I decline to adjudicate, but I’m glad to learn the word bombazine. It’s a dense weave, often of silk or wool combined with cotton.

*

Another work off view at the MFA is Saint Jerome, by the Venetian artist Jacopo da Valenza. The painting is distinctive for the rocky bridgescape(?) that extends into the sky behind the meditating saint. This is not something I saw on a previous visit. I know about it because it was the subject of a talk at the conference I was in Boston for, given by Gianmarco Russo of the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa. Russo identified a few possible influences for this strange vision, including Vittore Carpaccio’s Virgin and Child with Four Saints at the Musée du Petit Palais in Avignon. May his talk inspire the museum to take Jacopo out of storage, or even to organize an exhibition of landscape in Venetian painting.

*

I always assumed the vases that flank the painting in the image below were Chinese, but I’ve just looked them up and found that they’re actually Japanese (links: left vase; right vase). They are the same vases that appear in the painting that normally hangs between them, John Singer Sargent’s The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, a work that has been called “the American Las Meninas.”

The painting was not on view in March because it was in New York, or on its way there, for the Sargent exhibition at the Met. In its place hung a similarly sized and almost contemporary painting by Édouard Manet, the Execution of the Emperor Maximilian. An odd juxtaposition, the vases and the firing squad, but I can think of a few points in favor of it beyond the practical ones of size and date. Both the Sargent and the Manet owe a debt to a Spanish painting—in the latter case it’s not Velázquez, but Goya’s Third of May 1808. And then, Sargent was American (Florence-born, but still), and this is a gallery for American art, but might a European painting of an event in Mexico be granted temporary American status? Well, why not?

To conclude. At the beginning of last month’s post I wondered where in the hierarchy of American museums the MFA belonged. I proposed that five of our museums—the Met, MoMA, the National Gallery of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Getty— were “self-evidently magnificent”; I wasn’t sure if the MFA could be said to be in the same group. Now, almost fifteen thousand words later, I have two thoughts. One: as an encyclopedic museum, the MFA is second only to the Met.20 Two: the MFA could use a few more galleries, especially for Japanese and Dutch art.

While Bílá hora is really only a hill, and not a white one, either (the name comes from the light stone dug up there in Medieval quarries), it’s a nice place for a walk and a picnic, and under an hour by tram from the center of Prague. There’s also a Renaissance villa in the shape of a star there, the Hvězda.

The quote is from Elizabeth Stuart: Queen of Hearts, by Nadine Akkerman, 2021, p. 308. I am indebted to Clare Jackson’s review of Akkerman’s book in the London Review of Books.

The Meissen factory still makes this rhino; you can custom order one for €20,587.

The two cabinets were the subject of a 2014 article in the Burlington Magazine, Two coral cabinets made for Claude Lamoral I, Prince de Ligne and Viceroy of Sicily, by Mario Tavella.

Barbara Westman, the wife of Arthur Danto, was a talented artist somewhat in the manner of Saul Steinberg (she, too, drew New Yorker covers). I found an appreciation of her on the blog, Two Coats of Paint.

The 'Wayback Machine’ has a record of the painting as Don Baltasar Carlos with a Dwarf from September 27, 2019. The next preserved record, from April 16, 2023, reflects the name change.

Murillo and the Spanish School of Painting, by William B. Scott, 1872, pp. 72–73.

Portrayals of Christ after the flagellation (a subject with limited scriptural basis) were popular in Seville in the seventeenth century. There’s another one by Murillo at the Krannert Art Museum at the University of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign), and there are also versions by Velázquez (National Gallery, London) and Zurbáran (Parish Church Nuestra Senora del Carmen, Jadraque). See John F. Moffitt, “The Meaning of ‘Christ after the Flagellation’ in Siglo de Oro Sevillian Painting,” Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch, vol. 53, 1992, pp. 139-154

The subject was less common outside of Seville, but not unknown. There’s a version by the Flemish artist Gérard Seghers at the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Reims,

In addition to the three church interiors, the MFA also has a fourth Saenredam, the Town Hall of Haarlem. Both of the Coortes, the Ruisdael, and three of the four Saenredams are either from the 2017 gift or are other recent acquisitions or promised gifts.

In my April 2024 post on European art in Lisbon’s Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, I wrote about a painting of the Rest on the Flight into Egypt by the Florentine Artist Alessandro Allori, in which Joseph holds an American bird, a cardinal. I didn’t get too far while researching the painting for the Substack, but I kept at it afterwards and found enough material for a short article. “The Cardinalilio in Alessandro Allori’s Rest on the Flight into Egypt” will be published in Artibus et Historiae later this year or in 2026, as part of a special issue of the journal dedicated to my dissertation advisor, Catherine Puglisi.

Alison Kettering, “After Life: Rembrandt's Slaughtered Ox,” Artibus et Historia, 2019, p. 279.

The museum in Rotterdam translates: “There is one God, Allah, and Mohammed is his prophet”

The flow of Copley’s early paintings in the other direction has been more sporadic. The only ones I am aware of are three in the collection of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid.

Copley made two other versions of the painting, a full-size replica (at the MFA) and a reduced on (Detroit Institute of Arts).

The lecture, Morse at the Louvre, is about Samuel F. B. Morse’s painting, The Gallery of the Louvre, and more, generally, Americans in Paris in the early 1830s. It was given at the National Gallery of Art on September 26, 2011. In the quotation (which starts at 12:48) McCullough is referring to the friendship of Morse and James Fenimore Cooper.

My sources on Copley and the Izards: (i) Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., The Lure of Italy: American Artists and the Italian Experience, 1760-1914, 1992, cat. no. 4, pp. 156–58; (ii) Letters & papers of John Singleton Copley and Henry Pelham, 1739-1776, Library of American Art, 1970, p. 330; (iii) J. E. Manigault “Ralph Izard, the South Carolina Statesman,” The Magazine of American History with Notes and Queries, Volume 23, 1890, pp. 60–73; (iv) Jules David Prown, John Singleton Copley, National Gallery of Art, 1966, vol. 2, pp. 251–60.

The National Gallery of Art’s Southern Resort Town is not presently on view, nor are two more paintings atttributed to Smith at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

John Sartain, The Reminiscences of a Very Old Man, 1808–1897, 1899, p. 214.

I should say, though, that I haven’t been to Cleveland or Detroit.

Finally finished your piece on the Boston MFA.

So I saw the photo of the Manet execution where the Sargent group portrait used to be.

Weird.

I suppose you're working on the next article. What will it be?

First, a typo of sorts. You have the queen as a brother, not sister. You might want to change it.

I suppose I have read about half of the post while sitting in a busy business class lounge at JFK.

Perhaps dividing it into more than one post as you originally intended would have been a better choice, especially since the post is a series of individual pieces.

More than anything, you are a historian who loves telling good stories.

I enjoy hearing & reading them.

I'll read more about the Boston MFA another time.

Keep writing.

🦄💖