While staying in Palermo in April 1787, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and his traveling companion, the painter Christoph Heinrich Kniep, made an excursion to the Oreto River. Today this would be a trip to the suburbs, but at the time it meant visiting a “pleasant valley in the mountains,” an ideal place for Kniep to draw and for Goethe to look. All the makings of a delightful afternoon, but there was one problem: their guide.

The fair spring weather and the luxuriant vegetation lent an air of grace and peace to the whole valley, which our stupid guide proceeded to ruin with his erudition, for he started telling us in great detail how, long ago, Hannibal had given battle here and what stupendous feats of valour had taken place on this very spot. I angrily rebuked him for such an odious evocation of defunct ghosts. It was bad enough, I said, that from time to time crops have to be trampled down, if not always by elephants, still by horses and men, but at least one need not shock the imagination out of its peaceful dreams by recalling scenes of savage violence from the past.

He was very astonished that I, on such a spot, should not want to hear anything about classical times, and, of course, I could not make him understand my objections to this mixing-up of the past and the present.

He must have thought me still more of an eccentric when he saw me searching for pebbles in the shoals which the river had left high and dry, especially when I pocketed several specimens. Again, I could not explain to him that the quickest way to get an idea of any mountainous region is to examine the types of rock fragments washed down by its streams, or that there was any point in studying rubble to get the idea of these eternal classical heights of the prehistoric earth.

My haul from the river turned out to be a rich one. I collected nearly forty specimens, though I must admit they could possibly all be classified under a few rubrics. The majority are probably some kind of jasper or chert or schist. Some were round and smooth, some shapeless rubble, some rhomboid in form and of many colours. There was no lack, either, of pebbles of shell-limestone.1

*

Apart from a few visits to the library at the Met for research, and a quick look at the new Caspar David Friedrich exhibition there, I haven’t had time for museums lately. I wasn’t sure I could come up with anything for this newsletter, and was on the verge of skipping February, but then I read the above passage in Goethe’s Italian Journey, in which he scolds his guide for talking about Hannibal at the wrong moment and collects rocks by a river.

As the passage suggests, Goethe had a keen interest in geology. Later in the same month, passing through Caltanissetta in Sicily’s interior, he finds pectinites in the town’s paving stones. In Catania he collects lava, hoping the specimens may help to settle a dispute then raging in Germany over the nature of basalt. He is also granted access to a princely collection of amber. “Sicilian amber,” he writes, is different from northern amber in that “it passes from the color of transparent or opaque wax or honey through all possible shades of yellow to a most beautiful hyacinthe red.”2 I could go on. There are the zeolites of Jaci, there’s the pyrite he finds on the way to Messina, and of course there’s Mount Etna itself.

So I thought, if he could do it, why shouldn’t I try the same, especially since the one museum I can always find a moment for, the only one I walk past several times a week, is the Rutgers Geology Museum, in New Brunswick, New Jersey. This, to be sure, is taking a few steps down from the Louvre, but in its way it’s a storied institution. Its founding in 1872 predates that of several other museums I’ve written about, and it remains in its original home on the second and third floors of Geological Hall, a handsome building of Connecticut brownstone located in Old Queens, the oldest part of the Rutgers campus.

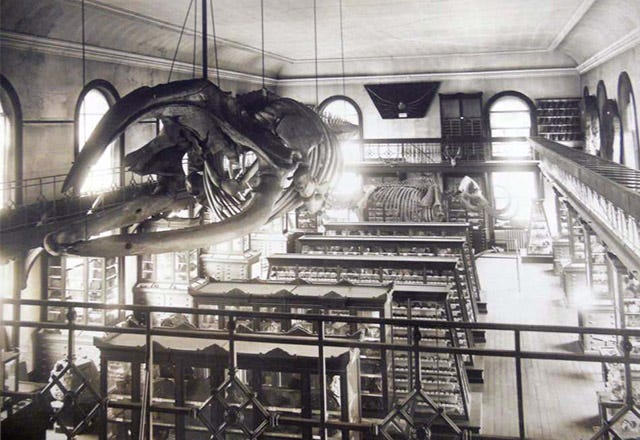

It’s old-fashioned as well as storied. In an age when many natural history museums have embraced the latest technology, the absence of digital screens here is refreshing. While it is not the case that the museum hasn’t changed a bit since the below photograph was taken—the whale skeleton is gone, and the old trapezoidal cabinets have been removed—the general scheme of display is the same.

The whale, a North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis), was found stranded in the Raritan River, just upstream from South Amboy, in May 1874. The incident is recounted in the Forest & Stream of June 4 of that year, with a long quote lifted from a story that ran in the New York Sun.

Many old fishermen, who by virtue of their calling were supposed to know all about whales, though none of them had ever seen one, cherished a pleasant fiction that the creature, being essentially a denizen of the briny ocean, getting accidentally into the river, had become blinded and bewildered with the unwonted effects of the fresh water, and moved on blindly to its fate without knowing where it was going to.

It is unclear to this twenty-first century reader what is pleasant about the fiction, but as a taste of Reconstruction-era journalese, with its cynical tone and superfluous adverbs, the passage is a treat. The Sun goes on to describe the whale’s unfortunate end.

The poor creature was shot with a rifle, hacked at with an ax, and at last killed with a harpoon.

Watching a lecture given by the museum’s director, Dr. Lauren Adamo, on the occasion of its fiftieth annual open house, I learned that whale bones are high in blubber content and rot unless treated. They are also heavy. Hang them from your ceiling at your peril. At some point Rutgers took the skeleton down; eventually it was given to Yale’s Peabody Museum. Today it is in the Boston Aquarium, though I’m not sure what remains of the original, the Ship of Theseus problem may apply here.

The other two big creatures in the 1896 photograph, the mastodon skeleton and the mounted crab on the far wall, are still at the museum. The latter, eleven feet from claw to claw, is a spider crab that the Japanese government sent to Rutgers as a token of appreciation. Quite a few Japanese attended the school in the nineteenth century, beginning in the late 1860s.3 As for the mastodon, a farmer dug it up in a New Jersey marl pit in 1869; George Cook, the founder of the museum, bought it for three hundred dollars.

But it would be contrary to the guiding spirit of the institution to devote too much space to these wonders. As William Valiant observed:

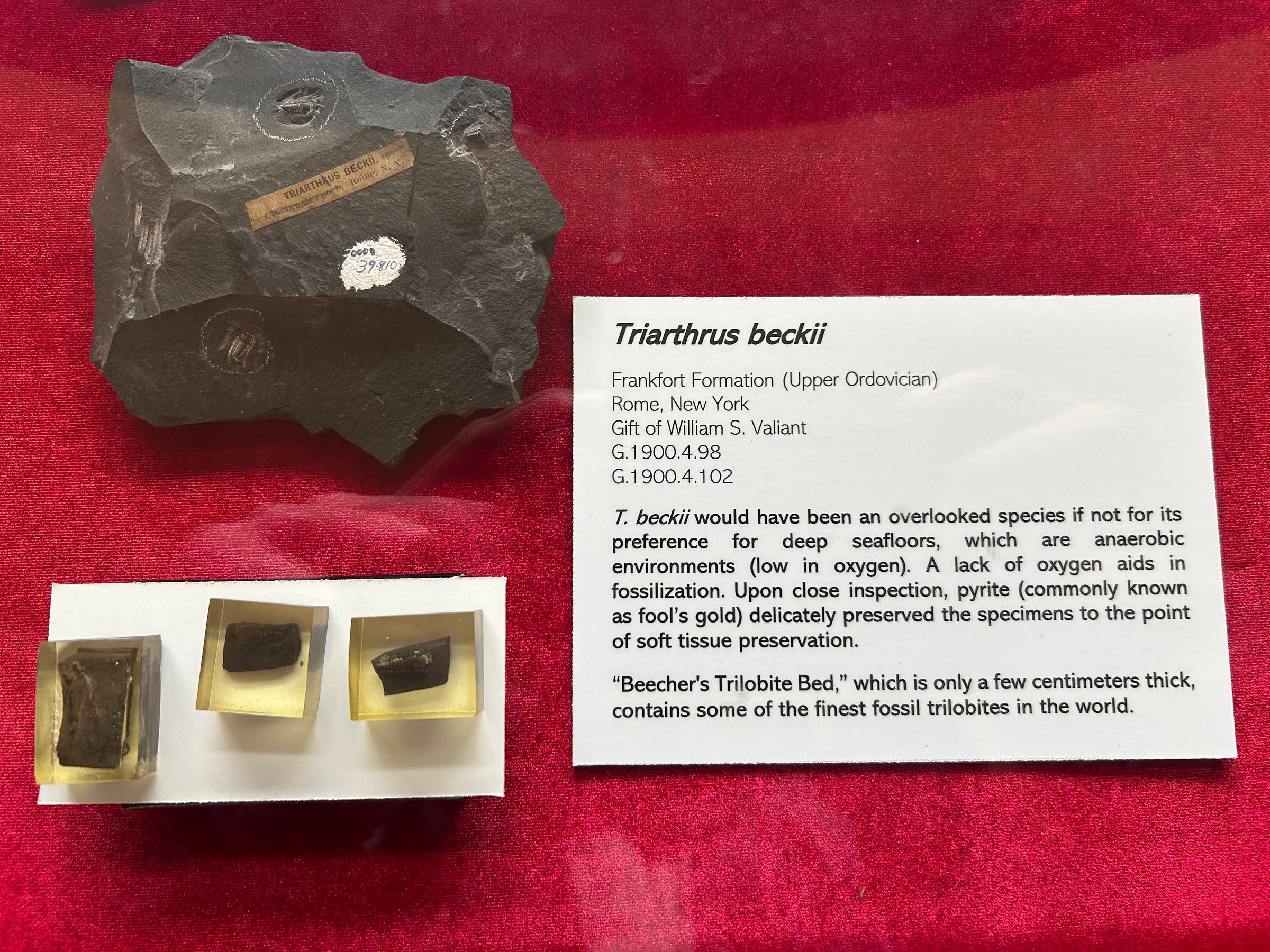

A museum adds dignity to a trifle; a pebble teaches the same lesson with the hundred ton boulder; the skeleton of a mouse occupies as much space in science as does the mastodon's huge frame.

Rutgers Museum is not a collection of freaks and curios, but a collection of scientific specimens, each one illustrating some important part of the sciences taught.

Valiant, born in Rome, New York in 1845, began hunting “stone trophies,” especially trilobites, at an early age. His formal education was limited—after losing his left arm in a mill accident at sixteen, he briefly attended school, but soon returned to the mill. He eventually began corresponding with trained geologists, and after making important trilobite discoveries in the early 1890s was offered the job of assistant curator at the Rutgers museum. Though he was later promoted to full curator, he never in his lifetime achieved the recognition he felt was his due. His disability and his lack of formal education left the choicest jobs, such as New Jersey State Geologist, out of reach. Today, however, he is credited with raising the museum’s standards of cataloguing and display. And how many of the state geologists of yesteryear ever get written up on Substack?4

*

By now I’ve been studying and teaching in New Jersey for the better part of a decade, but I still don’t know much about the state. American Pastoral taught me that Trenton has good water, and that this is important for two industries in particular, leather and beer. I’m sure I also picked up a few things from the Sopranos, but for the most part the New Jersey in my mind is as blank as the interior of Africa on a portolan chart.

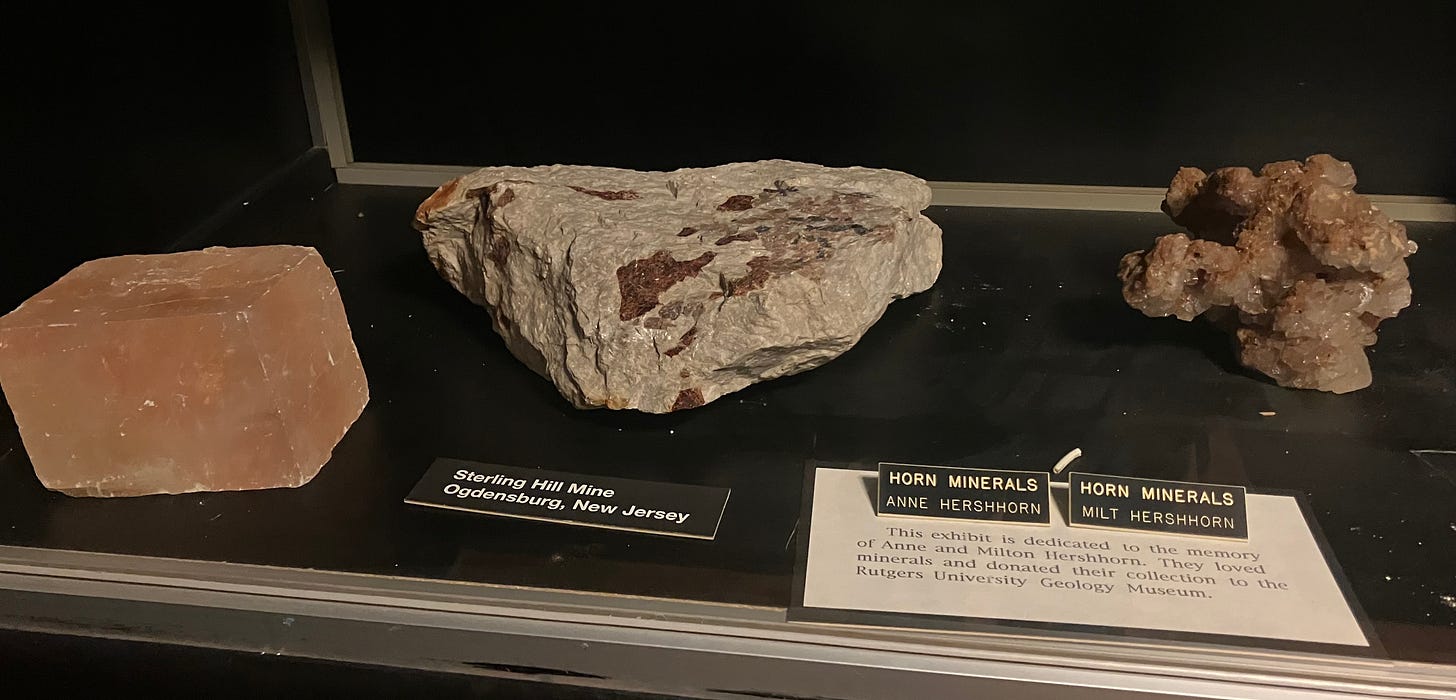

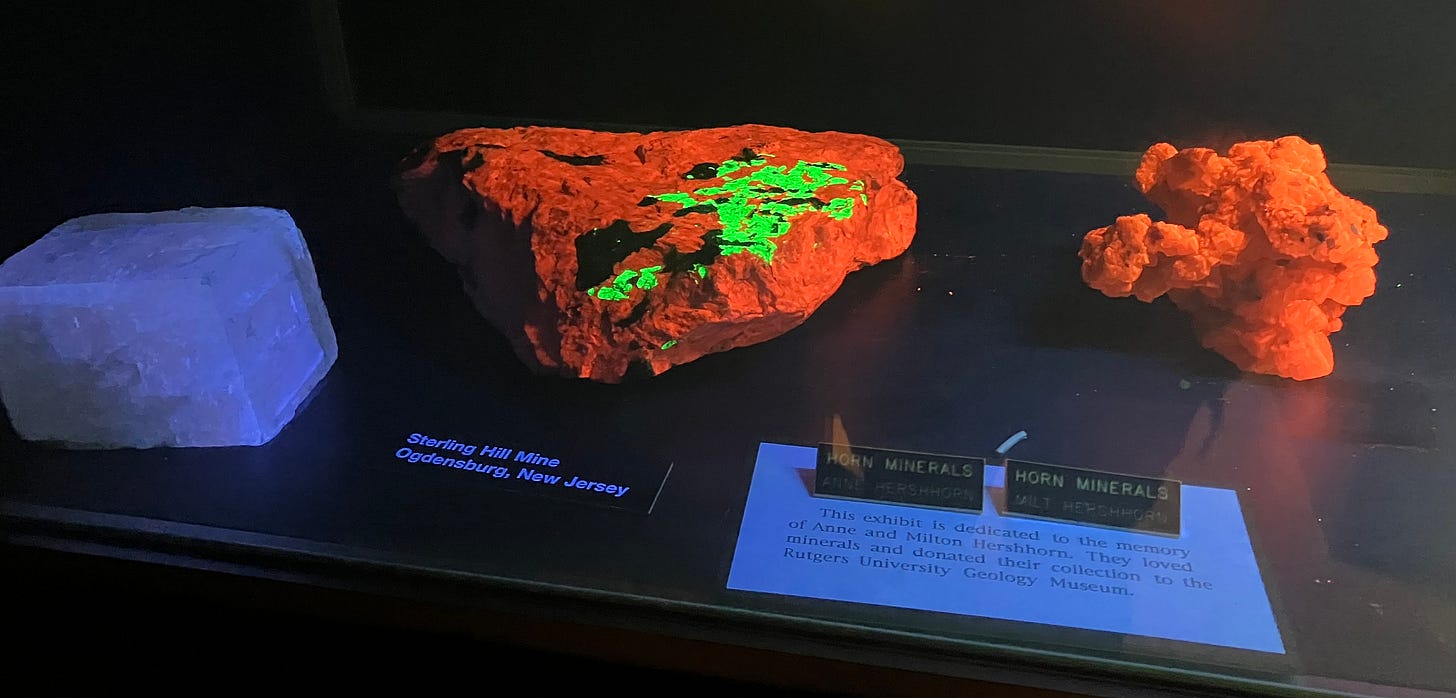

No surprise, than, that prior to visiting the Rutgers Geology Museum I was unaware of the state’s mining history. Dutch settlers took an interest in New Jersey’s mineral deposits in the seventeenth century, and in the eighteenth, around the same time that Goethe toured Sicily, samples from Sterling Hill in the northwest of the state were sent for testing to Wales, where it was determined that the ore in question did not contain enough copper or iron to be smelted profitably.

Later examination revealed plentiful zinc, which among its other uses is a component of brass. Serious mining began at Sterling Hill in the 1830s, 1.15 billion years after the Grenville orogeny, the geologic event that brought the ore into being in the first place. When the operation closed in the 1980s there were thirty-five miles of tunnels reaching 2,675 feet below ground.

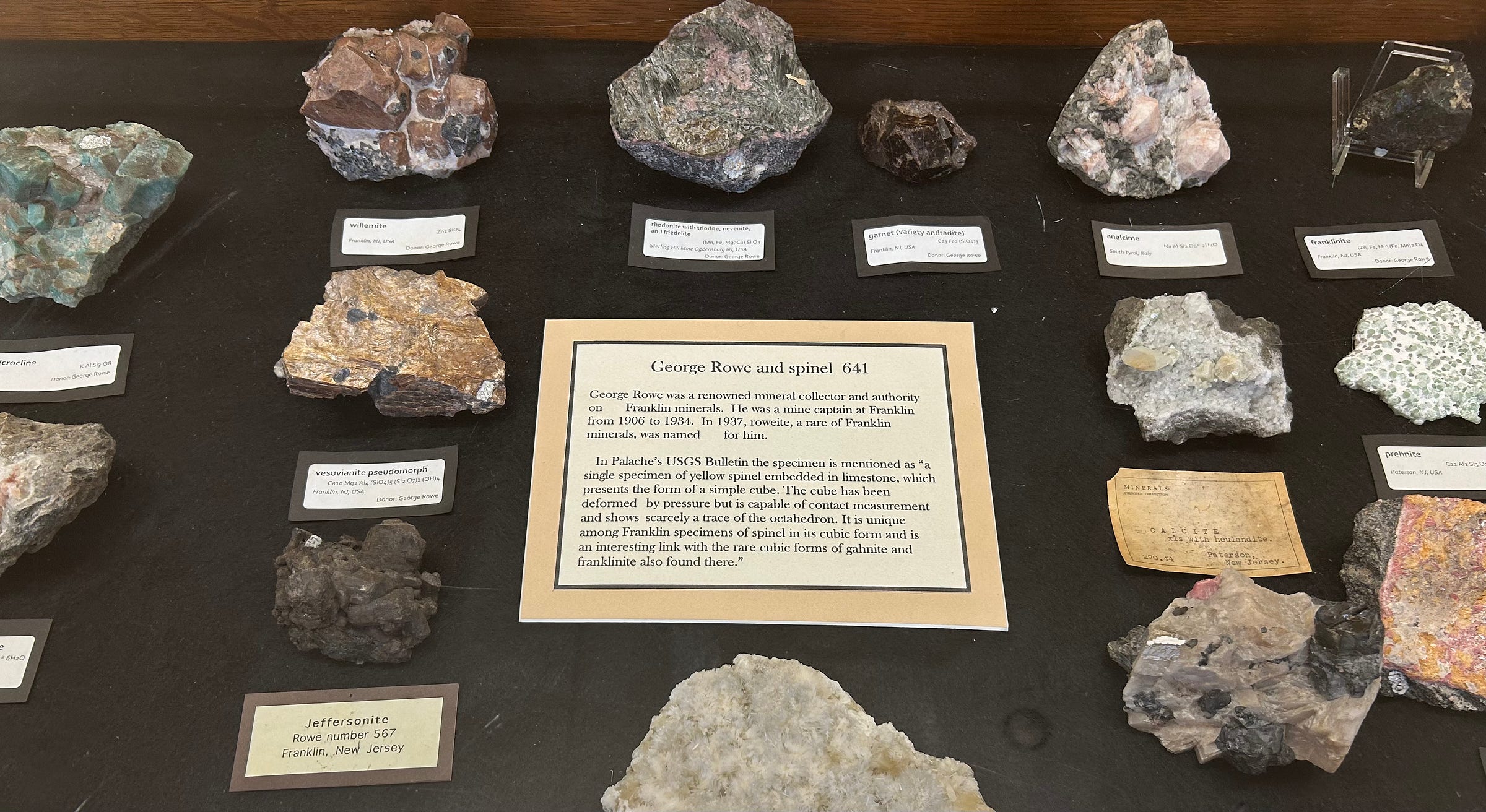

Many of the several hundred types of mineral in the deposits at Sterling Hill are rare; thirty-five have never been found elsewhere, apart from nearby Franklin. It was in Franklin, at the New Jersey Zinc Company, that George Rowe was mine captain for twenty-eight years. Rowe, born in 1868 in Cornwall, England, started his mining career at eleven, not when he was deemed old enough for shifts at the local copper mine, that could have happened earlier, but when his younger siblings (there were fifteen Rowes in all) were judged capable of taking over his duties in the family shop.

There were Cornish men working in mines throughout the United States, sending money back to their families in Cornwall; by the time Rowe was sixteen this group included some of his former colleagues. At eighteen it was his turn. He describes his departure in a memoir that was excerpted in Rocks & Minerals in 1986.

I purchased a carpet sack and got my belongings together, taking only the things I needed, as I planned to get more clothes when I arrived in America and could purchase a trunk to keep them in. The day set for leaving home was a time of sorrow and tears. We traveled the four miles to the railroad station with several of our friends and relatives. We took a train to Liverpool and said our final goodbyes. For some of us those goodbyes were truly final, as we never again saw those who waved from the platform.

Rowe spent his first twenty American years in Michigan, working in iron mines. He married the daughter of a coal dealer and started a family, before leaving for New Jersey and his new role as a mine captain in Franklin. Much of the memoir excerpt concerns the many changes in mining practices he observed in his long career, and the range of roles he held. He also takes pride in the public improvements he saw in Franklin, which included its first hospital and theater, a new school, and a Presbyterian church. He speaks disdainfully of the “labor agitators” who organized a strike, but in the paragraph after mentioning the strike he notes that the mine soon reduced the workday from ten to eight hours, without a proportional reduction in wages. The excerpt does not touch on the large mineral collection Rowe donated to the Rutgers museum in 1941, but in its final paragraph, speaking of the pleasures of retirement, he mentions his flowers.

I have some time to play in my flowers and watch the works of nature unfolding the handiwork of the Great Creator.

I’ve enjoyed learning about Valiant, the one-armed autodidact and trilobite hunter, and Rowe, the mine captain from Cornwall. They remind me of art collectors, and there may be an interesting analogy here. If Etta Cone is to the paintings of Henri Matisse as William Valiant is to trilobites, the acquisitive passions that drove Cone and Valiant may be compared. But can one also compare the creative urge that made Matisse paint to the fossilization of a Paleozoic arthropod? What does a Matisse have to do with a trilobite?

Maybe a lot, if the trilobite is the handiwork of the Great Creator. This, in fact, is the reasoning Baldassare Castiglione uses to explain why one should love art in his Book of the Courtier, published in 1528.

And truly he who does not esteem this art, seems to me very unreasonable; for this universal fabric that we see,—with the vast heaven so richly adorned with shining stars, and in the midst the earth girdled by the seas, varied with mountains, valleys and rivers, and bedecked with so many divers trees, beautiful flowers and grasses,—may be said to be a great and noble picture, composed by the hand of nature and of God; and whoever is able to imitate it, seems to me deserving of great praise: nor can it be imitated without knowledge of many things, as he knows well who tries.5

For a Renaissance Christian like Castiglione, the trilobite, like all of nature, is part of Gods’s “great and noble picture.” Matisse’s merit as an artist derives from his ability to imitate that picture.

This was not quite how Goethe saw things. Goethe never mentions a Creator, and he discriminates—his nature is one that at times may be improved on by a painter, and one in which some hills are devoid of mineralogical significance. Still, there is a reverence in his desire to observe and understand that seems inherited from the age of Castiglione. The division of the Renaissance cabinet of curiosities into the natural history museum and the art museum was well underway by the 1770s, but not for Goethe, at least to judge from his assessment of the Jesuit church in Messina.

My knowledge of the various substances out of which this splendour was composed helped me to discover that the so-called lapis lazuli was only calcara, but of a beautiful color I had not seen before, and assembled with superb skill.6

By now the division is complete. Fossils belong on the other side of Central Park, or down the Mall, or across the Maria-Theresien-Platz, in museums that are more for kids than adults. If you see a fossil in an art museum these days, you can be sure its label will explain that once upon a time there were cabinets of curiosities.

Not that the cultivated adults of the twenty-first century don’t revere nature, many do, but they are not so curious about it. A vague awareness of concepts like geologic time and natural selection is held to be sufficient; anything more than that is for specialists. One would be startled to find, in the letters page of the London Review of Books, an author’s barbed response to a critic’s condescending review of the latest work on basalt.7

So if I, visiting and writing about the Rutgers Geology Museum, have been unable to channel Goethe’s spirit of curiosity, if I would rather look at Etta Cone’s Matisses than William Valiant’s trilobites, maybe in part it’s because I’m a creature of my time, a time of humanistic snobbery towards the hard sciences. Maybe I am prevented from attaining universal curiosity because I flatter myself as having put away childish things. When looking up Goethe’s words, one of them brought back an early memory. A pectinite is a fossilized scallop shell. Such shells are plentiful at Calvert Cliffs State Park, in Maryland, which I visited as a child. It is said of Calvert Cliffs that there are fossil sharks’ teeth there as well as pectinites. You may imagine the bitterness of my disappointment when my parents took me there and I did not find one.

All of which is to say, a display of fossils and minerals like the one at the Rutgers Geology Museum has a special value for those of us who fail to take an interest in it. It gives us an opportunity to wonder if the failure constitutes a flaw.

*

In 1977 Jeanne Filler Scott, an art major at Rutgers who was a regular visitor to the museum, was given a commission to paint a Mosasaurus, an aquatic dinosaur whose fossils are found in New Jersey. The director of the museum at the time, Bill Selden, suggested she include ammonites, prehistoric cephalopods on whose fossils Mosasaurus tooth marks have been found, as prey. Am I wrong to think that if it were installed in the Modern galleries at the Met, next to a Warhol or a Frankenthaler, it would quickly become one of the most popular paintings in the museum?

I found Scott’s website (she’s still an animal painter, but no longer takes commissions) and wrote to ask if she would be willing to share memories of the commission. A quote from her reply:

I drew the mosasaurus as if you were underwater looking at the animal. I did not know it at the time, but when I went back to Rutgers for the unveiling of the restored painting in 2022 (45 years later!) he told me that he had not expected that kind of pose, that he had expected I would show the mosasaurus partially submerged on the surface. He never said anything about that at the time. I have not seen another painting that showed a mosasaur fully underwater, come to think of it. He said he would like me to put in some prehistoric fish as well as ammonites which I did. I know I brought the painting in to show him at least once while working on it to get his input. He said no one knew what color they were in real life.

In addition to Scott’s Mosasaurus painting, there’s also a sculpture of a Grallator, which is not a species but an ichnogenus, that is, a type known from footprints. From the ubiquity of their three-toed tracks in local fossil deposits it is clear that Grallators were once abundant in the region. No one at the museum knew the name of the sculptor.

*

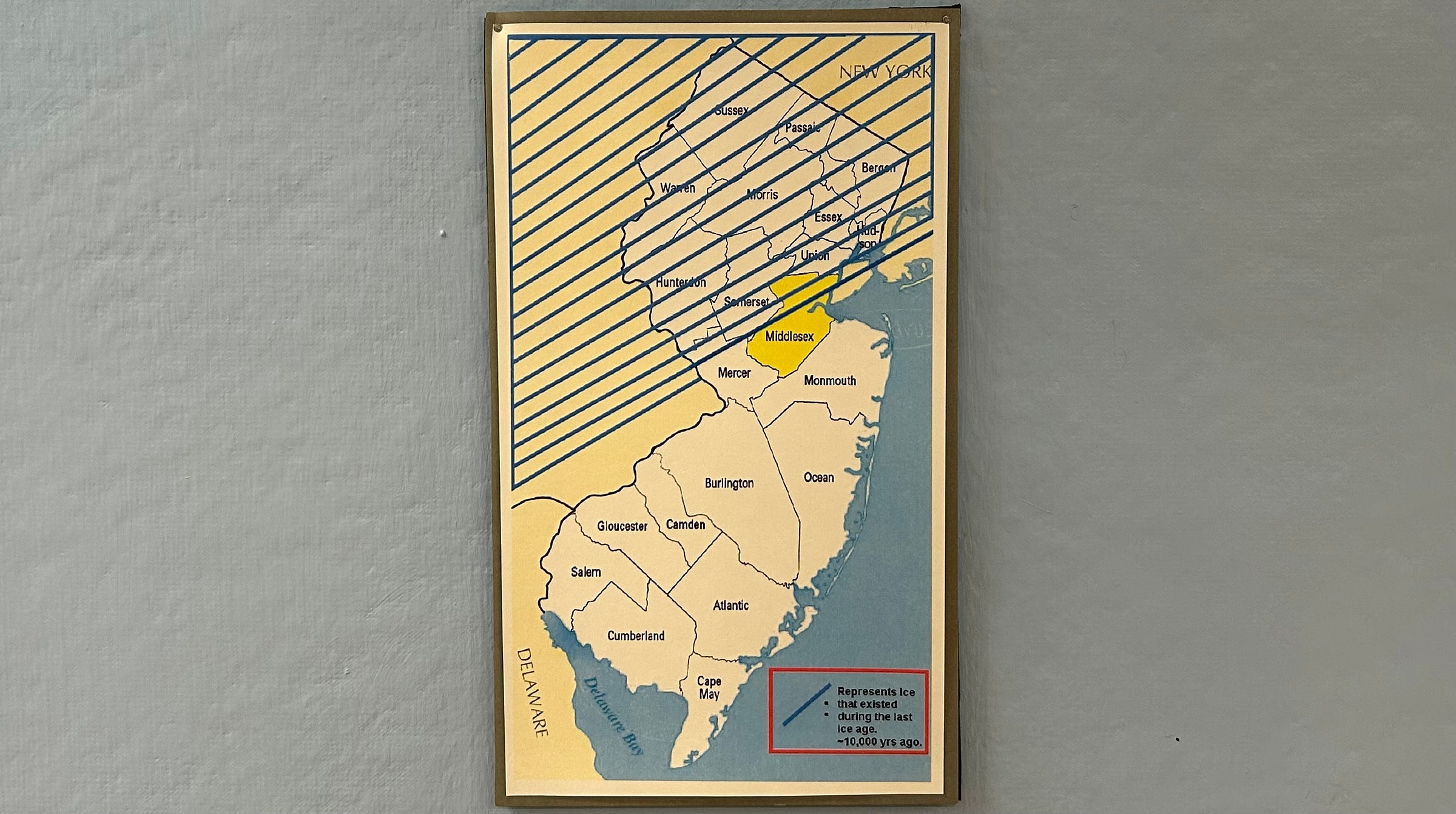

Finally, two maps of the state. The first one shows ‘Maximum Ice Coverage in New Jersey during the Last Ice Age.’ Can the division of the ice-bound and ice-free zones really have fallen right along the line of the Northeast Corridor, with the train tracks following it so precisely that, looking out the window on the north side of the train, one might imagine a saber-toothed tiger chasing a juvenile mastodon across the glacial sheet, and then with a turn of the head have a vision of wildflowers on the bank of a running stream? As the saying goes, se non è vero, è molto ben trovato.

The second map, which is not in the museum but on the ground floor of the building, opposite the entrance, is a relief map of New Jersey from 1893, with one inch corresponding to one mile and yellow lines for railroad tracks. The flatness of the neighboring states makes for a rejoinder to Saul Steinberg’s famous New Yorker cover. No, Mr. Steinberg, that’s not Kansas City you see from 9th Avenue. It’s not even Scranton.

Goethe, Italian Journey (Penguin Classics edition, translated by W. H. Auden and Elizabeth Mayer, pp. 229–30). A note points out that the guide was misinformed: “It was not Hannibal but Hasdrubal who was defeated near Panormus by Caecilius Metellus in 251 B.C.”

Italian Journey, p. 282

Rutgers has a page on this with lots of pictures. See also Fernanda Perrone Invisible Network: Japanese Students at Rutgers during the Early Meiji Period, Bulletin of Modern Japanese Studies, 34, 2017, pp. 448–68.

The quotations are taken from a brochure Valiant wrote for the museum in 1899. The story of Valiant’s life is told in a talk given by Carol McCarty of the Rutgers History Department.

Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier, translated by Leonard Epstein Opdycke, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1903, pp. 65–66.

Italian Journey, p. 298. Messina’s Jesuit church, San Giovanni Battista, was attached to the earliest college founded by the Jesuit order. Both the church and the college were damaged in a 1908 earthquake and demolished a few years later. Today the site is home to the University of Messina.

Granted, Verso has published books on fossil capital, and fossil fascism, and a discussion of one of these prompted an exchange in the letters page of the LRB. But the subject is the merits of ecoterrorism, not the transformation of zooplankton into shale.