I didn’t say much, last month, about the Yale University Art Gallery. I wrote about archaeological finds from Dura-Europos, a border town on the eastern fringe of the Roman Empire; I wrote about a collection of early Italian paintings that some decades ago underwent what now seems to have been an ill-conceived conservation treatment; and I talked about a nonexistent still life by Édouard Manet, the product of a trick my memory played on me after a previous visit to the museum in 2017.

It’s a big museum. Three floors of permanent display spread across three connected buildings, and a fourth floor with temporary exhibitions. As befits a museum attached to a university founded in Connecticut in 1701, there is a great deal of early American art. More surprising, there is also a collection of Modernist European works whose display in New York in the 1920s predated the opening of MoMA by several years. I’ll get to these, but first I want to mention Manayunk, a 1947 painting by the Philadelphia artist Walter Stuempfig. It’s the odd cityscape in a row of six paintings in a gallery of twentieth century American art. The other five are interiors, though three of these have windows or doorways. Stuempfig is the unknown in the group. Half the paintings in the row are by Edward Hopper, whom you’ve heard of. Depending on how versed you are in American art, you may also have heard of Horace Pippin and Charles Sheeler.

The order in the picture above, from left to right, is Pippin, Sheeler, Hopper, Stuempfig, Hopper, Hopper. Had it been up to me I would not have hung the room this way. There’s another Hopper on the opposite wall, and it’s about the same size as these. I would have done the obvious thing, kept the four of them together.

Which might explain why I’m not a curator? As Hoppers go (and granted, he is not for all tastes, just like not everyone likes to watch film noirs) these are good, I think equal to the best ones at the Whitney.1 I sometimes wondered, during my afternoon in this museum, if it would be better known, and more often visited by day trippers from New York, if it only had fifty or sixty modern paintings and none of the older stuff. Maybe, but to get to the point, whichever wall Yale chooses for these Hoppers gets to be special, and whichever other paintings accompany them get a chance to shine. This is true enough of the Pippin and the Sheeler, which hang to the left of Sunlight in a Cafeteria, a painting that one might call a daytime version of Nighthawks. But how much more true of Stuempfig’s Manayunk, on the other side of Sunlight in a Cafeteria, next to the other two Hoppers, Western Motel and Rooms by the Sea. Here are all six of the paintings, starting closest to the doorway with Rooms by the Sea.

Lots of institutions have works by Stuempfig, but they’re all in storage.2 The Forbes family owned dozens of his paintings, which they displayed from time to time in the ground-floor gallery of the former Forbes Building at Fifth Avenue and West Twelfth Street. But the Forbes’s sold their building to NYU in 2010, moved the magazine to Jersey City, and auctioned off the collection. Stuempfig has a Wikipedia page, but it averages just three visits a day, against fifty for Sheeler, fifty-seven for Pippin, and nearly a thousand for Hopper. In short, Stuempfig is remembered, but only barely.

I do not mean to suggest, by writing about him here, that his paintings are undervalued, that he is a neglected master, that it’s time for an exhibition. For that I’d want to see more. But with this single painting of a working class neighborhood in Northwest Philadelphia, maybe the only work of his on view in a major museum, and surely the only one displayed between paintings by an artist of the stature of Hopper, he holds his own.

Wikipedia has a quote about Stuempfig from Robert Sturgis Ingersoll, longtime president of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

A layman's chat with him would constitute a lesson in late 16th century and early 17th century Italian art. His heroes were Caravaggio, Degas and Eakins. One would risk acrimonious rebuttal if making a disparaging remark with respect to any one of them and earn a more violent rebuttal to a remark in praise of American Expressionism.

Having outed myself, in my discussion of Matisse’s early Nice years, as someone with reactionary tastes, I will further admit that even if I might not have done it myself I love Stuempfig for this standing athwart of history and yelling Stop at admirers of Jackson Pollock. But I’m a little surprised, on the basis of Manayunk, to hear one of his heroes was Caravaggio, because my first thought on seeing the painting was of Vermeer and Proust—there it is, I thought, the little patch of yellow wall.3 And Caravaggio was not a painter of little yellow patches.

But maybe Stuempfig liked to hold forth on Vermeer as well, and Ingersoll forgot to mention it? Either way, I imagine it was patches of light on walls that got Stuempfig onto this wall, because Hopper’s paintings have them, too. Jan Vermeer, Edward Hopper, Walter Stuempfig. Painters of light on walls.

*

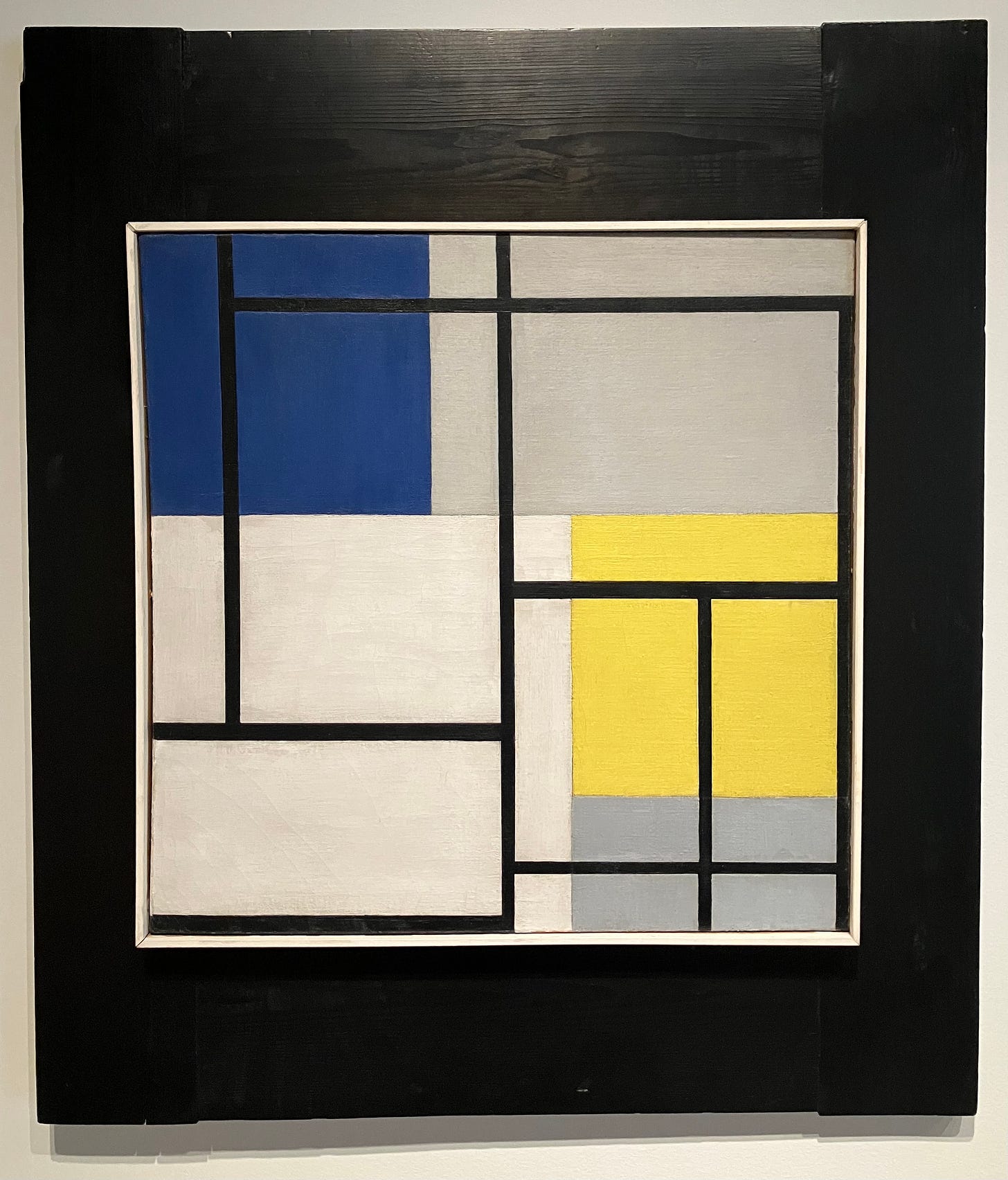

In 1920 three artists associated with the Dada movement founded the Société Anonyme, Inc., an organization devoted to the collection, exhibition and promotion of modern art in the United States. Two of the three, Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp, are still well-known as artists; the third, Katherine Dreier, is remembered principally for this project. The name, which was chosen by Ray, is the result of a misunderstanding, or a joke, or both. Société anonyme is not French for ‘anonymous society,’ as a native speaker of English might guess, but for ‘corporation.’ So ‘Société Anonyme, Inc.’ means ‘Corporation Incorporated.’4

There had been the Armory Show in 1913, famous for the outcry and mockery provoked by Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, and from 1905 to 1917 Alfred Stieglitz had sometimes shown contemporary art in his gallery space on the top floor of 291 Fifth Avenue, but in 1920 there was no New York museum dedicated to displaying the work of living artists. Nor did the Société Anonyme ever become this sort of museum. It started out in two rented rooms of a townhouse on East 47th Street. In a letter sent to prospective members, Dreier wrote, “We want this little Museum of Modern Art to belong to the people—and as one of the people will you not contribute $5 or $10 by becoming a member for one year.”5

There was not space to display a permanent collection in the townhouse, long since demolished and today the site of the Consulate General of Ghana, but there were exhibitions and talks. Or maybe harangues would be a better word—I fear that a lecture given on a Friday evening in April 1921 by the painter and poet Marsden Hartley may have been typical.

The question on the lips of the rest of the world is naturally why is there no art in America? …It is because we have not yet learned the practical importance of true artistic sensibility among us.

Can you imagine paying fifty 1921 cents to hear this sort of thing? I can’t, but maybe there was a reception after, flappers to flirt with.

Even if part of the mission of the Société Anonyme was to scold the American public for being provincial, there was also the art itself—Kandinsky, Schwitters, Mondrian, Malevich, El Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy, Brancusi, Joseph Stella, and many others. As these names suggest, the collection was as geographically diverse as it was cutting edge. When traveling in Europe in search of the new, Dreier would ask artist friends to introduce her to artists she hadn’t heard of. One example: through Fernand Léger she met the Norwegian painter Ragnhild Keyser. I haven’t checked systematically, but I suspect you are unlikely to find Keyser’s work hanging anywhere else outside of Oslo.

Dreier, born in 1877, grew up in Brooklyn Heights, the daughter of German immigrants. Her father had risen to partner in a steel and iron firm, and her parents’ deaths in the 1890s left her financially independent, which is to say, a step below rich. Lack of funds forced her to close the East 47th Street gallery not long after it opened. In the years that followed she focused on exhibitions elsewhere; there was one at the Worcester Art Museum towards the end of 1921, and another in 1923 at Vassar College. Then, in 1926, came the Société Anonyme’s finest moment, when Drier organized the International Exhibition of Modern Art, a show of over three hundred works by contemporary artists held at the Brooklyn Museum. Today it is usual to think of the art of the early twentieth century in terms of discrete movements. These are presented in survey books in an orderly sequence, Constructivism, De Stijl, and so on. But for the last six weeks of 1926 they all were thrown together in Brooklyn. In addition to large galleries the exhibition included four small, walled-off spaces decorated with furniture from Abraham & Straus, the department store where, as Dreier put it, “the big middle class Brooklynites buy.” Her hope for these mini-rooms was they they would show visitors “how Modern Art looks in the home.”

Among those who came to the exhibition was Alfred H. Barr, Jr., at the time a professor of art history at Wellesley College. Three years later Barr would be chosen as the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, an institution that from the beginning, thanks to the Rockefeller family, had the money that the Société Anonyme always lacked. During the thirties Dreier and Barr kept up cordial relations. Barr wanted loans for exhibitions, and he hoped that in the long run that the Société Anonyme collection would end up at MoMA; Dreier played along because Barr was a useful contact. Underneath the civility each resented the other. Dreier (and Duchamp) disliked Barr’s curatorial choices, preferring the haphazard display of the Brooklyn Museum show to Barr’s scrupulous categorization. For Barr, the Société Anonyme was competition, and a reminder that he could be called an upstart.

When it wasn’t let out for an exhibition somewhere, Dreier kept the Société Anonyme collection at The Haven, her estate in West Redding, Connecticut. In the late 1930’s, fatigued from years of running the organization and facing health problems, she developed a plan to convert the estate into a permanent display space, to be called ‘The Country Museum.’ But as ever for Dreier, the necessary funds could not be raised. Not so wealthy as to be able to donate The Haven, she hoped to find backers to endow an organization to buy it from her. In 1941, when it was clear this was not going to happen, Dreier met with Charles Seymour, President of Yale, and Theodore Sizer, director of the Yale museum, to talk about giving the Société Anonyme works to the university. Both men liked the idea. At the time Yale possessed just two abstract paintings, so this was a chance to go from having next to no modern art to having one of the best collections in the country. Still, there were obstacles. “The lady is difficult,” Sizer told Seymour, and in a letter to a museum associate he wrote,

Were the lady to set no conditions we could afford to swallow a lot (& let a large portion of the collection lie dormant for better times)… but she (far smarter than superficially apparant [sic] quite properly wants it used in all sorts of (interesting) ways—& we to pay the bill… My laudable desire to find out… will probably result in losing a nice juicy fish right off the hook… the lady… likes much attention—& you can load the compliments on with a trowel… so long as we land this fish.

They did land the fish, doubtless to the exasperation of Barr in New York. In the years that followed Dreier made additional donations from her personal collection, and after her death in 1952, Duchamp, the executor of her estate, gave still more works. All told, Yale has over a thousand objects that once belonged to the Société Anonyme or Dreier herself, by nearly two hundred artists.

*

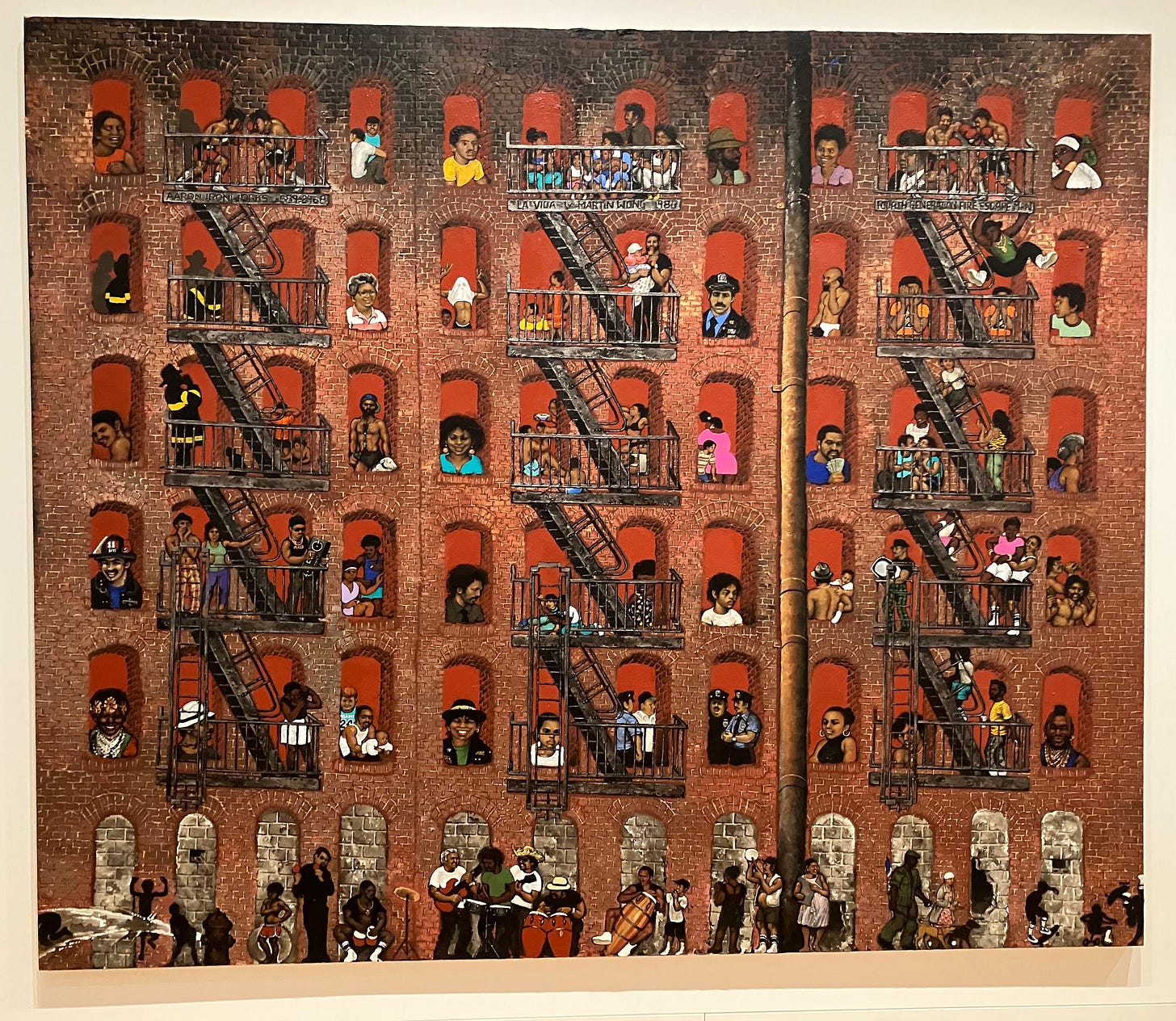

I close with four more favorites from my day at Yale. La Vida, by the American artist Martin Wong, is, of all things, a painting made in New York in 1988. I say of all things because New York art has never interested me much. I don’t think I could explain what’s significant about Dan Flavin’s work in neon if my life depended on it. Or for that matter Keith Haring’s graffiti paintings—aren’t they just boring? Basquiat I guess I could talk about, because I saw the movie, and fine, I will admit to loving Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen. In general, though, downtown art is not my thing, so I was surprised when I started looking at this painting, and kept looking, and looking and looking. Maybe the difference is that it’s not just a painting made downtown, by an artist associated with one scene or another, but a painting of downtown.

From 1982 to 1994 Wong lived and worked in a top floor apartment in the tenement building at 141 Ridge Street, in the heart of the Puerto Rican Lower East Side. Through his kitchen window he could see another tenement across the street, and it was this building that he used as the stage set for La Vida. It’s a large painting, seventy-six square feet, with countless red bricks, sixty windows, three fire escapes, and over a hundred figures. Friends, lovers, neighborhood characters, celebrities, boxers, cops with mustaches. A man in his underwear talks on the phone; another fans out some cash; a third, in sunglasses, stands on a fire escape with a boom box. On the fifth floor a child pulls a white t-shirt over his face to play ghost. A few windows over, in the leftmost dwelling, firemen have gathered, faceless silhouettes, the yellow stripes of their uniforms almost glowing. Is there a fire? But there’s red inside everywhere, not just here. Down on the street level the windows are bricked up. A seven-piece salsa band has set up out front, while off to the side a child jumps into the spray of a fire hydrant. There’s so much here; I only scratch the surface.

Wong was no stranger to urban life when he moved to New York in 1978. Though born in Oregon in 1946, he had grown up in San Francisco’s Chinatown. In the mid-nineties he returned there to live with his parents, who took care of him until he died from AIDS-related complications in 1999. A documentary shot during his last years reveals him to have been a kind, soft-spoken man with wry humor and a winning laugh. Rest in peace.

*

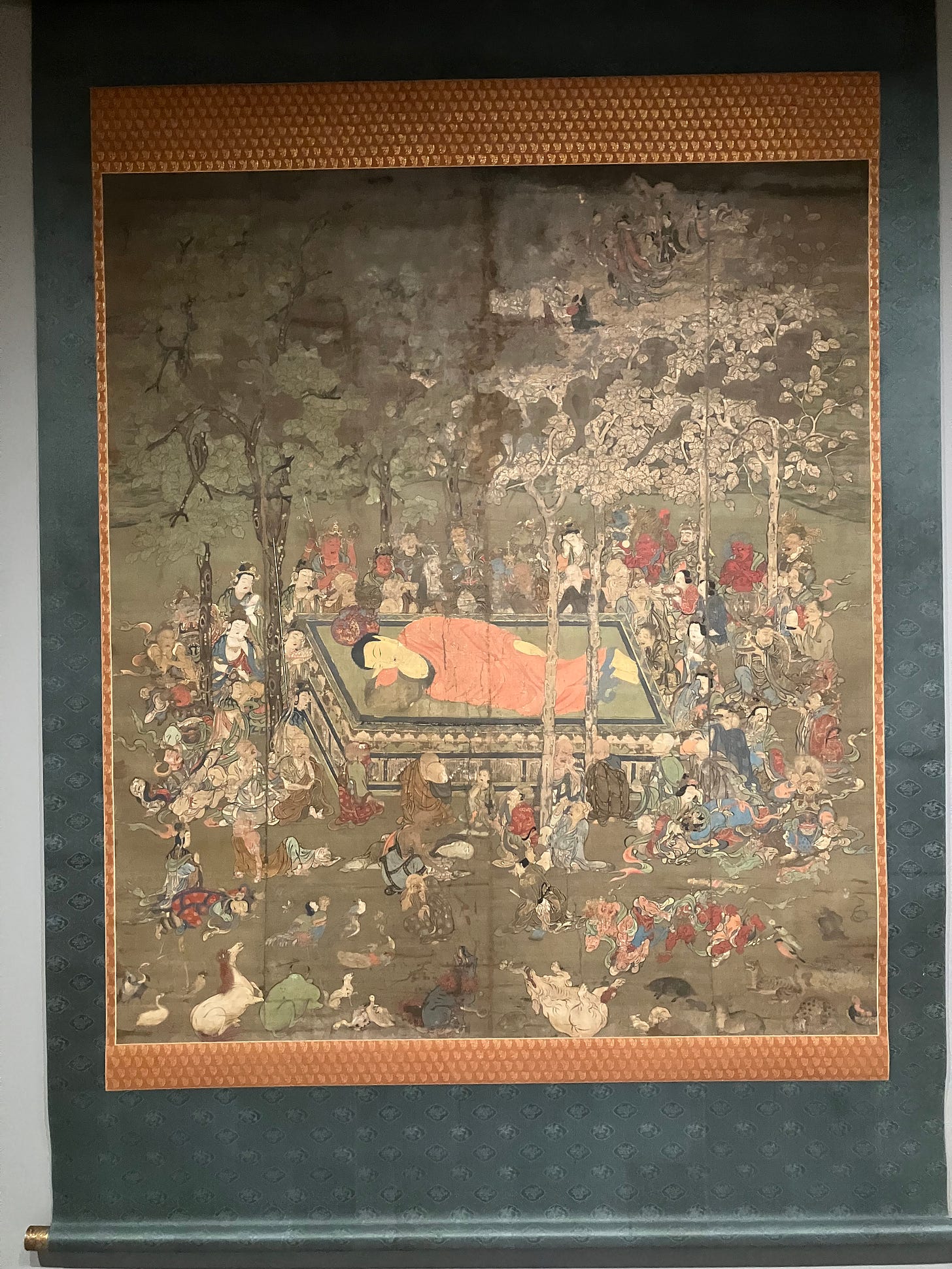

The Buddha’s final death, following which he escaped the cycle of reincarnation, is known as the parinirvana. This happened at what is now Kushinagar in the Indian province of Uttar Pradesh, in the fifth century BC. Yale possesses a Japanese portrayal from the fourteenth century, painted on silk and attributed to the artist Myōson. Buddha lies on a couch in the center, surrounded by an array of boddhisatvas, disciples and patrons, and even his mother, Maya, who has descended from the sky with a host of attendants. There are also demons among the mourners, and birds and animals, thirty-two species. While there is a scriptural basis for their inclusion, prior to the fourteenth century, depictions of the parinirvana were not so biodiverse. As Mimi Hall Yiengpruksawan put it, writing in the Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin in 2007, “the animals of medieval Japan, the denizens of its fields and streams, have come to take their place, prominently, at the death of the Buddha.” She continues,

It is possible that they are intended to remind us that we, too, may one day find ourselves among them. Animals were once humans, and are destined to be humans at some later point in the deep karmic grammar of the universe. It is perfectly reasonable that our approach to the dying Buddha is through the animals; there could be no more eloquent a statement of the antiquity of the human-animal bond than this. The animals seem to mirror the scene that unfolds at the center of the painting: the elephant lies prone just like the Buddha…

I am unqualified to comment on these matters, I only want to point out how charming it all is. Some animals are in anguish; others calmly carry an offering of a flower or a sprig. Among the latter are a tree sparrow and the female of a pair of bullfinches. Dear creatures! May you too achieve nirvana!

*

Around the turn of the nineteenth century the self-taught New England artist John Brewster, Jr. painted Sarah Prince, of Newburyport, Massachusetts. She is seated at a piano and holds an unfinished sheet of music titled The Silver Moon. The Silver Moon was a love song by the English composer James Hook, written in 1794 and thereafter popular on both sides of the Atlantic. Why the music in the painting is cut off after two lines is unclear. Perhaps Prince was in the process of copying it herself, or perhaps the Prince family only paid Brewster enough to include the song’s title and opening. Either way, I’m glad to know of Brewster, he belongs in the pantheon of early American folk artists, alongside Joshua Johnson, Rufus Hathaway, Edward Hicks, and the rest.

As for Sarah Prince, she was a teenager when Brewster painted her. Prince grew up with her country, and grew old with it. She married Samuel Brown Doane in 1807, and settled with him in his native Boston. By the time the last of her nine children was born in 1825 the Era of Good Feelings was coming to an end. She was a grandmother in Andrew Jackson’s America and a great-grandmother in Abraham Lincoln’s. She died in 1867. There were thirty-six states. The transcontinental railroad was nearly complete. Portraits were generally made not by itinerant painters, but in photography studios. Supposing she held on to the painting, the hit song from 1794 was both a constant presence in her life and an ever more distant memory. The Silver Moon—the full score is at the Library of Congress, but I have not been able to find a recording.

*

Finally, from the Ancient Americas gallery, a vessel with rodents. Did Leo Lionni see this or a similar object before creating his famous children’s book, Frederick? If so, the descendants of the Nasca should sue his estate for royalties.

*

Two postscripts. First, the room guards at this museum are vigilant. I heard more visitors scolded for getting too close to paintings in one afternoon at Yale than at the rest of the museums I’ve been to this year combined. It turns out, though, that one may attempt to stand one’s ground. A guard called me out when I was in front of the famous van Gogh café scene. I asked him if he was sure; it was like challenging a parking ticket. And reader, I won the round. Just be careful, he told me, after admitting, on closer inspection, that I was fine.

Second, a final hidden strength of the Yale museum that merits mention is its YouTube channel. I don’t think any institution has posted so many interesting lectures. Start with one of the many by John Walsh former director of the Getty (and a member of Skull and Bones), or else watch Andrew Robison of the National Gallery of Art explain What Makes Piranesi Great.

The Whitney has more than two hundred Hopper paintings, but only a few of these (Seven A.M., Early Sunday Morning, A Woman in the Sun, South Carolina Morning) seem to me to be as perfectly ‘Hopperish’ as the ones at Yale.

There are Stuempfigs at the Whitney, the Phillips Collection, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Woodmere Art Museum, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, MoMA, and the Met.

This is a reference to a scene in The Captive, the final volume of Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past. Proust’s character Bergotte, an ailing novelist, reads in a review about a little patch of yellow wall in Vermeer’s View of Delft, which had been brought to Paris for an exhibition. Bergotte, having thought he knew the painting thoroughly, leaves home in spite of his illness to look for the little patch of yellow wall. He finds it, feels regret about his writing career, has a heart attack, and dies.

"That's how I ought to have written," he said. "My last books are too dry, I ought to have gone over them with a few layers of colour, made my language precious in itself, like this little patch of yellow wall."

For this section I am indebted to The Société Anonyme: Modernism for America, edited by Jennifer R. Gross (Yale, 2006).

For a rough conversion multiply by 16. Membership, in 2024 dollars, was $80 to $160.

Although I visited the Yale Museum, I didn't have time to explore the galleries of Modern art.

The wall with the Hoppers, et al (note how my memory finds the most familiar name first), is well arranged. The Pippin is, perhaps, a token, if the theme is light.

The story of how Yale beat Barr is a good one. You are an entertaining narrative writer.

Haring might not have been a great artist, but he was original & fun.

Basquiat threw up anything on paper or canvas, and like Pollack, was too lazy to craft a finished work. Even abstract paintings require care in execution.

I'm probably even more reactionary than you.